Digital Timeline:

Teaching Resources:

This section provides downloadable resources that educators can incorporate into their curricula. Click at the bottom of each item for the downloadable file.

Introduction to the book "Living with Gandhi: Experiments in Utopia" by Karline McLain (downloadable PDF)

Check back soon! The book Living with Gandhi: Experiments in Utopia by Karline McLain is forthcoming in 2026. The Introduction to the book will be shared here after the book's official release.

Discussion Questions for the book "Living with Gandhi: Experiments in Utopia" by Karline McLain (Downloadable PDF)

Discussion Questions for the book Living with Gandhi: Experiments in Utopia by Karline McLain

Gandhi gave a lot of thought to the concept of “universal wellbeing” (sarvodaya) during his lifetime. How would you personally define “universal wellbeing”? In what ways does your definition overlap with Gandhi’s? In what ways does your definition depart from Gandhi’s?

At his intentional communities Gandhi and his coresidents engaged in a wide variety of experiments in their everyday lives to try to facilitate universal wellbeing. For instance, to promote equality and self-sufficiency the residents tried to equally share the labor (no matter their race, religion, caste, or gender), growing and cooking their own food, building their own houses, making their own clothing, and running their own schools and microbusinesses. Which residential experiments with daily life do you find most compelling, and why? Which do you find least compelling, and why?

Gandhi tried to create more inclusive communities in his historical time and context, and had both successes and failures in this regard. In our own historical time and context, what steps can we take to create communities that emphasize greater belonging as well as inclusion?

If you lived during Gandhi’s time, do you think you would have been interested in joining any of his intentional communities in South Africa or India? If so, which one and why? If none, why not?

Think about the community you live in. What would your community look like if it was intentionally designed for the purpose of enhancing universal wellbeing? How might the physical space need to change? What daily practices might need to change? What attitudes might need to change?

Think about your everyday lifestyle. What is the larger impact (socially, politically, environmentally, etc.) of your individual micro-level practices on the wellbeing of the larger macro-level community (this community could be defined as your family, school, town, nation, etc.)? Which of your practices help to enhance the greater wellbeing? Which of your practices might endanger the greater wellbeing?

Gandhi believed that cultivating an attitude of self-discipline was needed for universal wellbeing. What do you think it means to flourish as an individual while simultaneously living well in community with one another? Do you agree that there must be some individual limits placed in order to foster the enhancement of life for the greater good? If so, what sort of limits do you advocate and why? If not, why not?

Gandhi increasingly emphasized the virtues of self-sacrifice and voluntary suffering at his intentional communities, and he believed that some causes are worth dying for. Do you think there are causes worth dying for? If so, which cause(s)? Do you think Gandhi’s coresidents who were willing to die were willing to do so for a cause, for the community, or for Gandhi’s charisma?

How do you personally define “utopia”? What core values undergird your definition of utopia? What does this mean for how you might define “dystopia”?

How can we create communities that are flexible enough to allow for multiple and even contrasting definitions of universal wellbeing and utopia?

Timeline of Gandhi's Communities (Downloadable PDF)

Timeline of Gandhi’s Communities

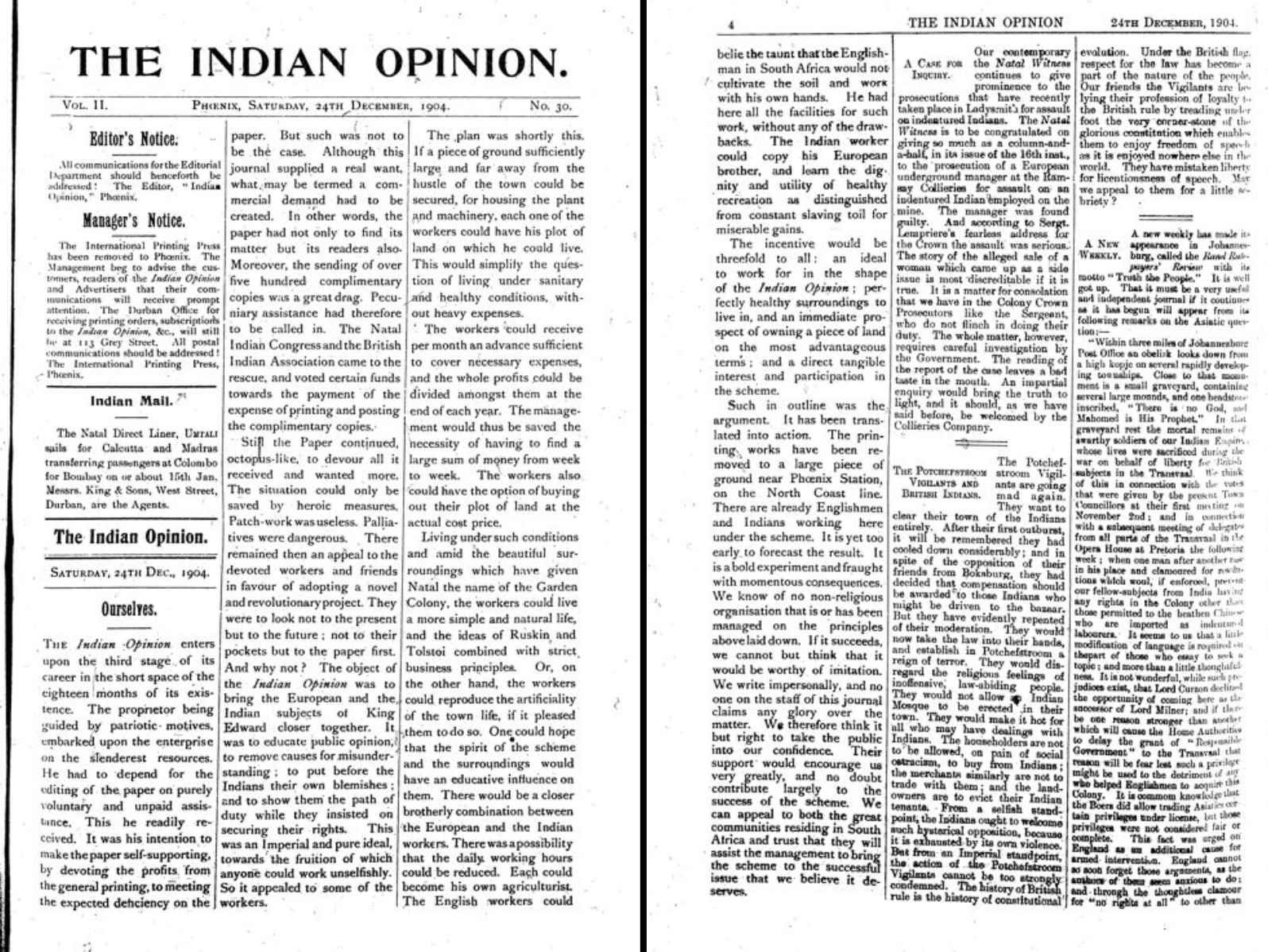

1904 Gandhi founds Phoenix Settlement (outside Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa), his first intentional community, and relocates the Indian Opinion printing press to this settlement.

1906 Gandhi and coresidents from Phoenix Settlement begin engaging in nonviolent protest of the Asiatic Registration Act (also known as the “Black Act”), advocating for greater equality for Indians living in South Africa.

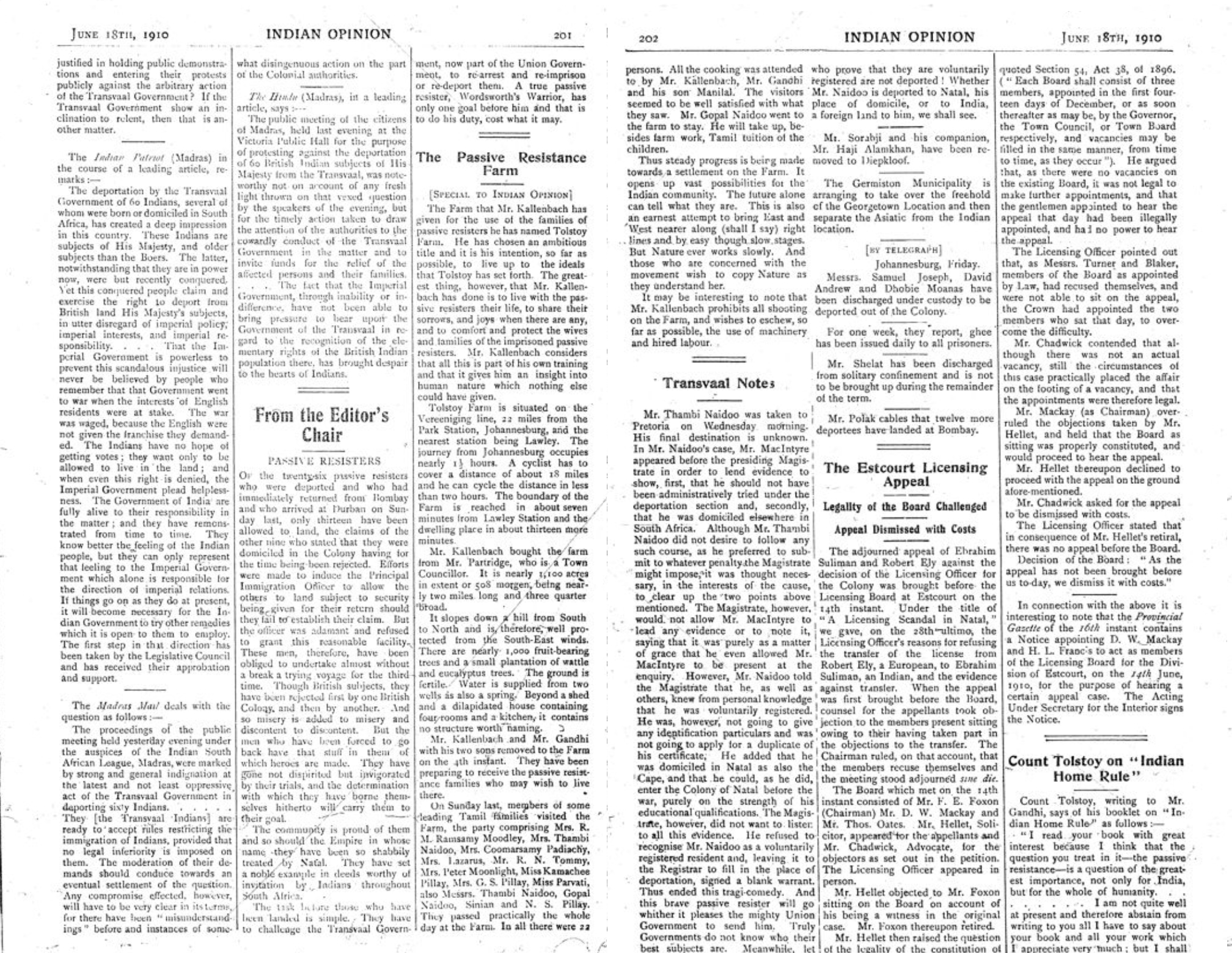

1910 Gandhi and Hermann Kallenbach co-found Tolstoy Farm (outside Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa), Gandhi’s second intentional community.

1913 Gandhi and coresidents from Tolstoy Farm lead the Great March, a nonviolent protest against racial injustice on behalf of Indians living in South Africa.

1914 Gandhi and Kallenbach close Tolstoy Farm; Gandhi departs South Africa to return to India, along with his immediate family and approximately two dozen coresidents from Phoenix Settlement and Tolstoy Farm. The Tolstoy Farm land is eventually sold, and its buildings razed. Phoenix Settlement remains a living community into the 1970s, before becoming a heritage site.

1915 Gandhi founds Satyagraha Ashram at Kochrab Village (Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India).

1917 Gandhi founds Sabarmati Ashram (outside Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India), moving the Satyagraha Ashram community to Sabarmati Ashram, which becomes Gandhi’s third major intentional community.

1917 Manilal Gandhi, Gandhi’s second eldest son, returns from India to South Africa to lead Phoenix Settlement, which he does until his death in 1956, at which time Manilal’s wife Sushila Gandhi assumes leadership of Phoenix Settlement until it disbands in the 1970s.

1921 Gandhi establishes a small satellite of Sabarmati Ashram, called Paunar Ashram, in Wardha (Maharashtra, India) and sends Vinoba Bhave from Sabarmati Ashram to manage it.

1930 Gandhi and seventy-eight coresidents leave from Sabarmati Ashram to begin the Salt March and to lead the larger Salt Satyagraha nonviolent anticolonial campaign.

1933 Gandhi disbands and closes Sabarmati Ashram. Today it is preserved as a heritage site.

1936 Gandhi moves to Segaon Village, which becomes Sevagram Ashram (near Wardha, Maharashtra, India), Gandhi’s final intentional community and his home until his death. To this day, Sevagram Ashram remains a living community for a small group of residents, and is also preserved as a heritage site.

1942 Gandhi launches the Quit India campaign from Sevagram Ashram, a nationwide anticolonial campaign for India’s independence.

1947 India attains independence.

1948 Gandhi is assassinated by Nathuram Godse.

A Day In The Life at Gandhi's Communities (Downloadable PDF)

A Day In The Life At Gandhi’s Communities

4:00 a.m.: Wake up. Residents awoke with the morning bell before sunrise and had fifteen minutes to quickly brush their teeth and rinse their faces.

4:15-4:45 a.m.: Morning prayer. The morning prayer was held on the designated communal prayer ground, a simple square plot of land demarcated for this use. Gandhi or another coresident would lead the morning and evening prayer services, and the expectation was that all residents would attend. Prayer was ecumenical, incorporating scripture readings and devotional songs from Hindu, Muslim, Christian, and other traditions.

5:00-7:00 a.m.: Breakfast and free time. After prayer it was time for a simple vegetarian communal breakfast. Responsibility for preparing the communal meals and cleaning up after them rotated among all residents. In the free time after breakfast one could exercise, bathe, socialize, read, or engage in correspondence.

7:00-10:30 a.m.: Manual labor. This included the varieties of work necessary for the self-sufficiency of the intentional community: farming (growing vegetables and fruits, milking cows, grinding grain, etc.), sanitation, and meal preparation. All adult residents were expected to take turns in each of these areas of labor. For minors the time designated for manual labor was the time for their classes, and teachers were expected to educate the children in the above areas of manual labor as well as the study of history, geography, mathematics, writing, and Indian languages.

10:45 a.m.-12:00 p.m.: Lunch and rest. A simple vegetarian communal lunch was served, followed by time to rest.

12:00-4:30 p.m.: Manual labor. This included the same varieties of work as the morning manual labor session. At different intentional communities Gandhi and his coresidents experimented with additional types of labor for self-sufficiency: at Phoenix Settlement this included operating the printing press to publish the newspaper Indian Opinion; at Phoenix Settlement and Tolstoy Farm the residents learned to make sandals out of rope and carve bowls and spoons out of wood; at Sabarmati Ashram and Sevagram Ashram spinning was added as an expected form of daily manual labor.

4:30-5:30 p.m.: Recreation time. Residents could again exercise, socialize, read, or engage in correspondence.

5:30-7:00 p.m.: Dinner and free time. A simple vegetarian communal dinner was served, followed by time to clean up and relax.

7:00-7:30 p.m.: Evening prayer. In addition to ecumenical scripture readings, lessons, and hymns, Gandhi often used the communal prayer times to give short speeches on current issues and events to the community members.

7:30-9:00 p.m.: Recreation time.

9:00 p.m.: Bedtime. When the evening bell rang, all residents were expected to retire for the night.

Slideshow of Gandhi's Communities (Downloadable PDF)

Documents:

Video and Photo Gallery:

Featured Coresident:

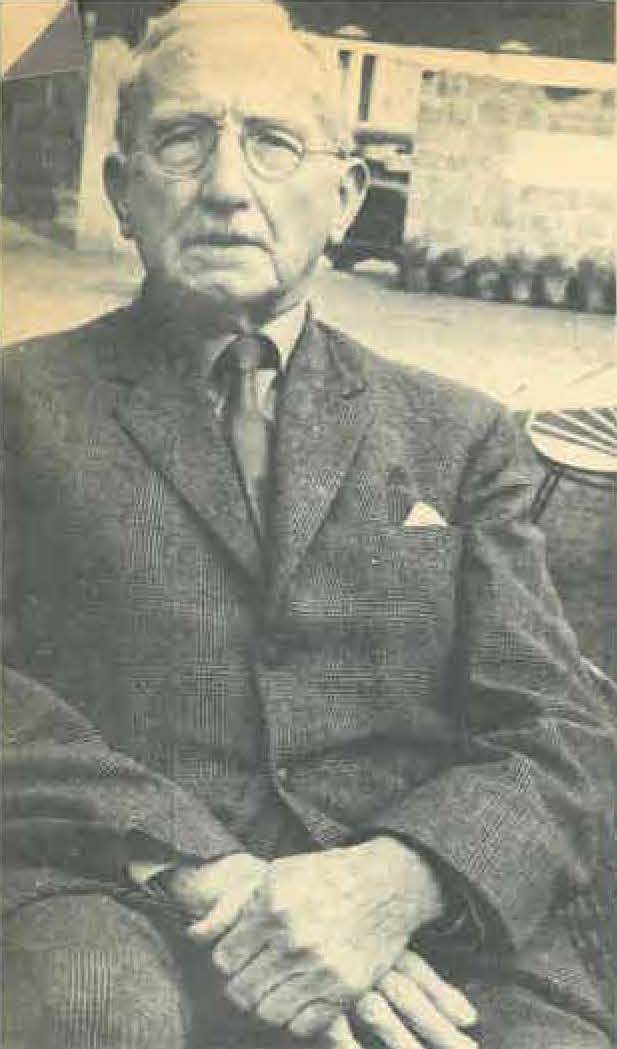

Albert West

Albert West was originally from Lincolnshire, England. He was twenty-four years old and running a printing operation in Johannesburg, South Africa, when he first met Gandhi in 1903. They encountered one another at a vegetarian restaurant in Johannesburg, and formed a quick friendship. Gandhi turned to West for help when he learned that his newspaper, Indian Opinion, was in financial distress. Gandhi asked West if he would consider moving from Johannesburg to Durban in order to take over the press operations for Indian Opinion. West agreed, and in the fall of 1904, he alerted Gandhi that Indian Opinion was running at a significant loss. Gandhi decided to travel from Johannesburg to Durban to meet West and together try to sort out the newspaper’s financial situation. On the overnight train Gandhi read an essay by John Ruskin titled “Unto This Last,” and was so influenced by the essay that he decided to immediately put its ideals into practice and found his first intentional community, and he invited West to join him.

Gandhi proposed to Albert West that they move the printing press to a remote location outside Durban, where Gandhi, West, the press workers, and a cohort of like-minded friends could live and work together as equals. West readily agreed to this proposal, and later recollected being drawn as much to the utopic idea of living and working on a collective farm as he was to Gandhi himself. West was one of the first residents at Phoenix Settlement. In 1908, West’s marriage to Ada West (nee Pywell) was celebrated at Phoenix Settlement, and his new bride joined the growing community. Albert also brought his elder sister, also named Ada (who came to be known as Deviben), from England to join the community, and his mother-in-law, Mrs. Pywell (who came to be known as Granny). Albert and Ada’s children, Hilda and Harry, were born at Phoenix Settlement.

When Gandhi departed South Africa in 1914 to return to India, Albert West elected to continue living at Phoenix Settlement with his family, helping to run the community and ensure that it continued to fulfill its mission. West served as editor of Indian Opinion until Gandhi’s second-eldest son, Manilal Gandhi (who returned to South Africa from India in 1917), assumed this role in 1920.

Citing the Living with Gandhi Archive:

McLain, Karline (editor). Living with Gandhi Archive. Bucknell University: http://livingwithgandhi.org.