Gandhi's Coresidents

This page presents brief biographical sketches of some of the coresidents who chose to live with Gandhi and undertake the collective quest for utopia at one or more of his intentional communities. Beyond their daily labor, these coresidents contributed significantly to the intellectual life of the community and its socio-political reform efforts. The entries are organized by community (in chronological order), and then alphabetically by the coresidents’ last names.

Phoenix Settlement

Gandhi founded Phoenix Settlement in 1904 near Durban, KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. This was Gandhi’s first intentional community, and his primary home until 1910. Inspired by the writings of Ruskin and Tolstoy, as well as the teachings of Theosophy, here Gandhi sought to build a multiracial and multireligious community of equals. Together with his coresidents, Gandhi farmed the land and operated a printing press, as they endeavored to establish a just society, one that was committed to providing equal wages and living conditions for all residents regardless of race, religion, or gender. During Gandhi’s time in residence this community housed approximately 70-80 residents.

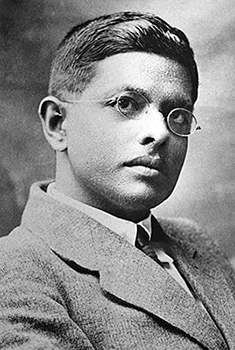

Harilal Gandhi

Harilal Gandhi (1888-1948) was born in Rajkot, India. He was the eldest son of Gandhi and Kasturba. As a young man, Harilal lived at Phoenix Settlement from 1906-1910, and then at Tolstoy Settlement from 1910-1911. From an early age Gandhi began training Harilal to lead civil disobedience movements. In 1908, when Gandhi and his coresidents at Phoenix Settlement began to plan their protest of the Asiatic Registration Act, Gandhi selected nineteen-year-old Harilal to lead it. Harilal was first arrested for civil disobedience in July of 1908. Gandhi served as his lawyer in court, and requested that Harilal receive the maximum sentence. Harilal was imprisoned for seven days with hard labor. Gandhi wrote in his Indian Opinion newspaper that going to jail was an important part of Harilal’s education, and he encouraged others to follow in Harilal’s footsteps and flood the jails in protest of the unjust Asiatic Registration Act.

After his first arrest, Harilal was imprisoned for civil disobedience five additional times during his years in South Africa, and each prison sentence he received was longer than the previous one. Phoenix settlers began to refer to him as “Chhote Gandhi” (“Little Gandhi”) in reference to his willingness to endure prison just like his father. In 1910, after just being released from a six-month stay in prison, Harilal and his brother Manilal joined Gandhi and Hermann Kallenbach at Tolstoy Farm, where they began preparing this second intentional community for additional inhabitants. Gandhi upheld Harilal and Manilal as exemplars, teaching the youth at Tolstoy Farm that just as he and his sons had done, so too could they survive time in jail, and ideally even learn to thrive there. Gandhi recruited Harilal to give regular talks to the community members about what to expect while incarcerated.

By 1911, Harilal concluded that he did not want to live at Tolstoy Farm any longer, nor did he want to spend additional time in prison. Harilal had repeatedly asked his father to send him to England for professional education, but Gandhi repeatedly told Harilal that an education on the farm and in prison was sufficient for him and his younger brothers. In May of 1911, Harilal confronted his father, and decided to leave South Africa and sail home to India. Unfortunately, the relationship between Gandhi and his son Harilal never recovered.

Kasturba Gandhi

Kasturba Gandhi (1869-1944) was born in Porbandar, India. She met Gandhi when they were both young teenagers, in a marriage arranged by their parents. When Gandhi accepted a position in South Africa in 1893, Kasturba initially stayed in India. However, after Gandhi decided that he would stay in South Africa longer than his initial twelve-month contract, Kasturba moved to there to join him. Her first two sons, Harilal and Manilal, were born in India, while her youngest two sons, Ramdas and Devdas, were born in South Africa. In the summer of 1906, Kasturba and her sons moved to join Gandhi and the newspaper press workers at Gandhi’s first intentional community, Phoenix Settlement.

The transition to rural farm life and to a new set of communal rules at Phoenix Settlement was not easy for Kasturba, and she did not always agree with all of the communal rules that Gandhi sought to implement. For instance, Kasturba voiced her skepticism on multiple occasions about the alternative education her sons were receiving in place of attending more accredited educational institutions. Gandhi wrote about some of the disagreements they had in his autobiography as well as in personal correspondence, and occasionally discussed them in his public talks. We have less insight into Kasturba’s mindset, however, as she did not write about her life experiences.

Kasturba was in residence with Gandhi at all of his intentional communities. Although Kasturba and Gandhi remained married until her death in 1944, they practiced celibacy from 1906 forward. Kasturba grew politically active in South Africa, and she elected to participate in the Great March there in pursuit of greater civil rights for Indians. After Kasturba and Gandhi returned to India in 1915, Kasturba continued to participate in nonviolent anticolonial movements, including taking a leading role in the Dharasana Salt satyagraha of 1930 as well as the Quit India satyagraha of 1942. Kasturba received multiple prison sentences for participating in nonviolent civil disobedience movements, beginning with her first imprisonment in South Africa, and ending with her final prison sentence in India during the Quit India campaign. Kasturba died in the Aga Khan Palace prison in 1944.

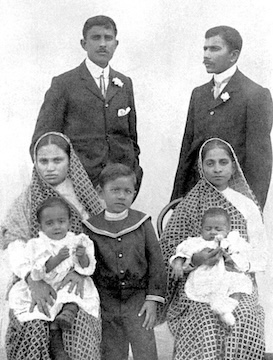

Maganlal Gandhi

Maganlal Gandhi (1883-1928) was born in India. He was Gandhi’s cousin once removed (the son of Gandhi’s older cousin Kushalbhai Gandhi), although Gandhi often referred to Maganlal his nephew. As a young man Maganlal went to South Africa in 1903 for employment opportunities, following in Gandhi’s footsteps, and initially worked in a merchant’s shop in Tongaat township (near Durban) and then at a branch store in Stanger township. In 1904, when Gandhi was establishing his first community, he invited Maganlal to join Phoenix Settlement. Maganlal was among the first residents to join the Phoenix community, and brought his wife Santok from India to join him in residence there. Their children were born at Phoenix Settlement.

Maganlal embraced life at Phoenix Settlement. He was a hard worker, and quickly began to contribute to the printing press work in order to publish the Indian Opinion weekly newspaper, as well as farming work. Maganlal also embraced Gandhi’s experiments, and while living at Phoenix Settlement he made vows to practice nonviolence and celibacy. As the residents of Phoenix Settlement and Tolstoy Farm grew more involved in anticolonial political campaigns, Gandhi increasingly looked to Maganlal to keep Phoenix Settlement, and Indian Opinion newspaper, operational while he and other residents were imprisoned for civil disobedience.

When Gandhi departed South Africa in 1914, Maganlal, Santok, and their children elected to return to India, where they helped to build Sabarmati Ashram, Gandhi’s third intentional community. Maganlal and Santok took on increasing responsibilities at Sabarmati Ashram, with Maganlal serving as the de facto figure in charge whenever Gandhi was away. Given their orthodox Hindu background, Santok and Maganlal struggled at times with some of the communal values, most notably the effort to remove untouchability and to cohabit with a Dalit family. When Maganlal passed away suddenly from pneumonia in 1928, Gandhi mourned his passing deeply, describing Maganlal in his obituary as the “watchdog” of Sabarmati Ashram in its material, moral, and spiritual aspects, and as dearer to him than his own sons.

Manilal Gandhi

Manilal Gandhi (1892-1956) was born in Rajkot, India. He was the second of four sons born to Gandhi and Kasturba. Manilal moved from India to South Africa as a child to join his father, where he was raised and educated at Phoenix Settlement and Tolstoy Farm. From an early age Gandhi began training Manilal and his elder brother Harilal to lead civil disobedience movements, and also prepared them to spend time in prison for anticolonial activism. In 1910, at the age of 17, Manilal served a three-month prison sentence with hard labor, his first imprisonment for civil disobedience. Gandhi praised Manilal for this, and upheld him as an example for the other children living in the community to emulate. Gandhi also praised Manilal and Harilal in his Indian Opinion newspaper, encouraging others to follow in their footsteps and flood the jails in protest of the discriminatory Asiatic Registration Act.

Whereas Harilal rebelled and left Gandhi’s communities, Manilal by contrast dedicated his life to Gandhi’s communities, and particularly Phoenix Settlement. Manilal returned to India with his parents when they departed South Africa, and lived with the Sabarmati Ashram community in India from 1915-1917. In 1917, Manilal returned to South Africa to lead Phoenix Settlement and ensure that its mission carried on after Gandhi’s departure, and he remained in this role for the rest of his life – though he occasionally returned to India for family visits, and in 1930 was one of the original marchers who accompanied Gandhi on the Salt March. Manilal also assumed the role of editor of the Indian Opinion newspaper that was printed at Phoenix Settlement (beginning in 1920).

Manilal married his wife Sushila Gandhi (nee Mashruwala) in 1927, and together they raised their children – Sita, Arun, and Ela – at Phoenix Settlement. There the family lived in “Sarvodaya House” until 1944, when they built a larger house of their own for their growing family, called “Kasturba Bhavan” (named after Manilal’s mother, Kasturba Gandhi). Under Manilal’s leadership, the Phoenix Settlement community engaged in a new round of nonviolent activism at Phoenix Settlement in response to increasing apartheid laws being enacted in South Africa after 1948. Before his death, Manilal actively defied these apartheid rules by entering places demarcated “Whites Only” and by participating in boycotts and other nonviolent acts of the Disobedience Campaign (1952) led by the African National Congress. Manilal was arrested and imprisoned numerous times for this activism. Manilal Gandhi died in 1956, at which time his wife Sushila became the leader of Phoenix Settlement.

Santok Gandhi

Santok Gandhi was born in India, and married at a young age to Maganlal Gandhi, who was Gandhi’s cousin once removed, whom Gandhi often referred to as his nephew. After her husband Maganlal followed Gandhi to South Africa in 1903 for employment opportunities, Santok followed her husband to South Africa in 1904. Later in 1904 Santok and Maganlal moved to Phoenix Settlement, becoming some of the earliest members of Gandhi’s first intentional community. Santok took part in the daily life at Phoenix Settlement, learning to farm and to help operate the printing press. Her children were born at Phoenix Settlement.

In South Africa, Santok and her husband became involved in helping to carry out Gandhi’s nonviolent civil disobedience campaigns. Santok and her children spent some time at Tolstoy Farm, Gandhi’s second intentional community in South Africa, when Maganlal was in prison in Johannesburg for civil disobedience. Santok participated in the Great March for Indians’ civil rights in South Africa in 1913, and was herself sentenced to three months in prison with hard labor.

When Gandhi departed South Africa in 1914, Santok, Maganlal, and their children elected to return to India, where they helped to build Sabarmati Ashram, Gandhi’s third intentional community. Santok and Maganlal took on increasing responsibilities at Sabarmati Ashram, with Maganlal serving as the de facto figure in charge whenever Gandhi was away. Given their orthodox Hindu background, Santok and Maganlal struggled at times with some of the communal values, most notably the effort to remove untouchability and to cohabit with a Dalit family. Santok elected to leave Sabarmati Ashram in 1928, after her husband passed away.

Henry Polak

Henry Polak (1882-1959) was originally from Dover, England. He first came to South Africa in 1903, and worked as a journalist on the editorial staff of The Transvaal Critic newspaper. Polak met Gandhi at a gathering of a vegetarian society in Johannesburg in March of 1904. Shortly after meeting Gandhi, Polak also began to work as a freelance writer for Gandhi’s newspaper, Indian Opinion, and grew increasingly involved in the “Indian Question” – the question of Indian civil rights in South Africa. Gandhi also persuaded Polak to study law, and then hired him to work in his law firm in Johannesburg.

In September 1904, Gandhi needed to make a trip from Johannesburg to Durban, where Indian Opinion was published, in order to deal with some financial affairs for the newspaper. As Gandhi boarded the overnight train for this trip, Polak gave him a copy of John Ruskin’s essay “Unto This Last” to read, suggesting that Gandhi might also find it interesting. Reading this essay was a transformative moment in Gandhi’s life, and sparked the idea for establishing his first intentional community, Phoenix Settlement, later that same year.

Polak married Millie Graham Polak (nee Downs), in 1905, with Gandhi serving as Polak’s best man during the wedding ceremony. Initially after their marriage, Henry lived half time at Phoenix Settlement with Gandhi and the other press workers, and travelled back and forth regularly between Phoenix Settlement and Johannesburg, while Millie remained in Johannesburg where she lived with Gandhi’s wife and children and became their teacher. In 1906, Millie moved to Phoenix Settlement to join Henry there, though she decided to return to Johannesburg after just two months. Henry, on the other hand, continued to split his time between Johannesburg and Phoenix Settlement for over a decade, working both on the Indian Opinion newspaper while at Phoenix Settlement, and also in his legal capacity out of Gandhi’s Johannesburg law office. After Gandhi had departed South Africa to return to India (in 1914), Henry and Millie Polak elected to go to India and lived briefly with him at Sabarmati Ashram, before returning to England.

Millie Graham Polak

Millie Graham Polak (nee Downs, 1881-1962) was originally from England. She had met her future husband, Henry Polak, at the London Ethical Society prior to Henry’s move to South Africa in 1903. After Henry to proposed to her, Millie moved from London to Johannesburg to join Henry, where they were married in 1905. Initially after their marriage, Millie lived in Johannesburg at the Gandhi household, where she took on the role of teacher to the Gandhi children. Henry, meanwhile, lived half time at Phoenix Settlement with Gandhi and the other press workers, and travelled back and forth regularly between Phoenix Settlement and Johannesburg.

In the summer of 1906, when Gandhi decided to shift his whole household to Phoenix Settlement, Millie relocated to the new intentional community with the Gandhi family. In her book Mr. Gandhi: The Man (published in 1931), Millie provides a vivid description of Phoenix Settlement at the time of her arrival, emphasizing that “the colony was to be as much as possible self-supporting, and life’s material requirements were to be reduced to a minimum,” and recalling that she was “disappointed and depressed” by her first view of the intentional community.

After just two months at Phoenix Settlement, Millie decided to leave and returned to the Gandhi house in Johannesburg, preferring a more urban setting over the rural farm life. Henry, on the other hand, had a greater fondness for Phoenix Settlement and continued to split his time between it and Johannesburg for over a decade. During these years Millie continued to aid the Gandhi family and support Gandhi’s causes from her Johannesburg location. After Gandhi had departed South Africa to return to India (in 1914), Millie and Henry Polak elected to go to India and lived briefly with him at Sabarmati Ashram, before returning to England.

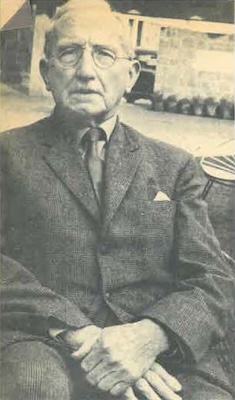

Albert West

Albert West (1879-19??) was originally from Lincolnshire, England. He was twenty-four years old and running a printing operation in Johannesburg, South Africa, when he first met Gandhi in 1903. They encountered one another at a vegetarian restaurant in Johannesburg, and formed a quick friendship. Gandhi turned to West for help when he learned that his newspaper, Indian Opinion, was in financial distress. Gandhi asked West if he would consider moving from Johannesburg to Durban in order to take over the press operations for Indian Opinion. West agreed, and in the fall of 1904, he alerted Gandhi that Indian Opinion was running at a significant loss. Gandhi decided to travel from Johannesburg to Durban to meet West and together try to sort out the newspaper’s financial situation. On the overnight train Gandhi read an essay by John Ruskin titled “Unto This Last,” and was so influenced by the essay that he decided to immediately put its ideals into practice and found his first intentional community, and he invited West to join him.

Gandhi proposed to Albert West that they move the printing press to a remote location outside Durban, where Gandhi, West, the press workers, and a cohort of like-minded friends could live and work together as equals. West readily agreed to this proposal, and later recollected being drawn as much to the utopic idea of living and working on a collective farm as he was to Gandhi himself. West was one of the first residents at Phoenix Settlement. In 1908, West’s marriage to Ada West (nee Pywell) was celebrated at Phoenix Settlement, and his new bride joined the growing community. Albert also brought his elder sister, also named Ada (who came to be known as Deviben), from England to join the community, and his mother-in-law, Mrs. Pywell (who came to be known as Granny). Albert and Ada’s children, Hilda and Harry, were born at Phoenix Settlement.

When Gandhi departed South Africa in 1914 to return to India, Albert West elected to continue living at Phoenix Settlement with his family, helping to run the community and ensure that it continued to fulfill its mission. West served as editor of Indian Opinion until Gandhi’s second-eldest son, Manilal Gandhi (who returned to South Africa from India in 1917), assumed this role in 1920.

Tolstoy Farm

Gandhi co-founded Tolstoy Farm with his friend Hermann Kallenbach in 1910 outside Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa. This was Gandhi’s second intentional community, and his home between 1910-1914. As Gandhi and his coresidents grew more politically active and engaged in nonviolent anticolonial protest, they needed a home that was both closer to the court and prison in Johannesburg, and could house the families whose primary breadwinners were serving prison sentences. At its peak Tolstoy Farm housed approximately 100 residents.

Harilal Gandhi

Harilal Gandhi (1888-1948) was born in Rajkot, India. He was the eldest son of Gandhi and Kasturba. As a young man, Harilal lived at Phoenix Settlement from 1906-1910, and then at Tolstoy Settlement from 1910-1911. From an early age Gandhi began training Harilal to lead civil disobedience movements. In 1908, when Gandhi and his coresidents at Phoenix Settlement began to plan their protest of the Asiatic Registration Act, Gandhi selected nineteen-year-old Harilal to lead it. Harilal was first arrested for civil disobedience in July of 1908. Gandhi served as his lawyer in court, and requested that Harilal receive the maximum sentence. Harilal was imprisoned for seven days with hard labor. Gandhi wrote in his Indian Opinion newspaper that going to jail was an important part of Harilal’s education, and he encouraged others to follow in Harilal’s footsteps and flood the jails in protest of the unjust Asiatic Registration Act.

After his first arrest, Harilal was imprisoned for civil disobedience five additional times during his years in South Africa, and each prison sentence he received was longer than the previous one. Phoenix settlers began to refer to him as “Chhote Gandhi” (“Little Gandhi”) in reference to his willingness to endure prison just like his father. In 1910, after just being released from a six-month stay in prison, Harilal and his brother Manilal joined Gandhi and Hermann Kallenbach at Tolstoy Farm, where they began preparing this second intentional community for additional inhabitants. Gandhi upheld Harilal and Manilal as exemplars, teaching the youth at Tolstoy Farm that just as he and his sons had done, so too could they survive time in jail, and ideally even learn to thrive there. Gandhi recruited Harilal to give regular talks to the community members about what to expect while incarcerated.

By 1911, Harilal concluded that he did not want to live at Tolstoy Farm any longer, nor did he want to spend additional time in prison. Harilal had repeatedly asked his father to send him to England for professional education, but Gandhi repeatedly told Harilal that an education on the farm and in prison was sufficient for him and his younger brothers. In May of 1911, Harilal confronted his father, and decided to leave South Africa and sail home to India. Unfortunately, the relationship between Gandhi and his son Harilal never recovered.

Kasturba Gandhi

Kasturba Gandhi (1869-1944) was born in Porbandar, India. She met Gandhi when they were both young teenagers, in a marriage arranged by their parents. When Gandhi accepted a position in South Africa in 1893, Kasturba initially stayed in India. However, after Gandhi decided that he would stay in South Africa longer than his initial twelve-month contract, Kasturba moved to there to join him. Her first two sons, Harilal and Manilal, were born in India, while her youngest two sons, Ramdas and Devdas, were born in South Africa. In the summer of 1906, Kasturba and her sons moved to join Gandhi and the newspaper press workers at Gandhi’s first intentional community, Phoenix Settlement.

The transition to rural farm life and to a new set of communal rules at Phoenix Settlement was not easy for Kasturba, and she did not always agree with all of the communal rules that Gandhi sought to implement. For instance, Kasturba voiced her skepticism on multiple occasions about the alternative education her sons were receiving in place of attending more accredited educational institutions. Gandhi wrote about some of the disagreements they had in his autobiography as well as in personal correspondence, and occasionally discussed them in his public talks. We have less insight into Kasturba’s mindset, however, as she did not write about her life experiences.

Kasturba was in residence with Gandhi at all of his intentional communities. Although Kasturba and Gandhi remained married until her death in 1944, they practiced celibacy from 1906 forward. Kasturba grew politically active in South Africa, and she elected to participate in the Great March there in pursuit of greater civil rights for Indians. After Kasturba and Gandhi returned to India in 1915, Kasturba continued to participate in nonviolent anticolonial movements, including taking a leading role in the Dharasana Salt satyagraha of 1930 as well as the Quit India satyagraha of 1942. Kasturba received multiple prison sentences for participating in nonviolent civil disobedience movements, beginning with her first imprisonment in South Africa, and ending with her final prison sentence in India during the Quit India campaign. Kasturba died in the Aga Khan Palace prison in 1944.

Manilal Gandhi

Manilal Gandhi (1892-1956) was born in Rajkot, India. He was the second of four sons born to Gandhi and Kasturba. Manilal moved from India to South Africa as a child to join his father, where he was raised and educated at Phoenix Settlement and Tolstoy Farm. From an early age Gandhi began training Manilal and his elder brother Harilal to lead civil disobedience movements, and also prepared them to spend time in prison for anticolonial activism. In 1910, at the age of 17, Manilal served a three-month prison sentence with hard labor, his first imprisonment for civil disobedience. Gandhi praised Manilal for this, and upheld him as an example for the other children living in the community to emulate. Gandhi also praised Manilal and Harilal in his Indian Opinion newspaper, encouraging others to follow in their footsteps and flood the jails in protest of the discriminatory Asiatic Registration Act.

Whereas Harilal rebelled and left Gandhi’s communities, Manilal by contrast dedicated his life to Gandhi’s communities, and particularly Phoenix Settlement. Manilal returned to India with his parents when they departed South Africa, and lived with the Sabarmati Ashram community in India from 1915-1917. In 1917, Manilal returned to South Africa to lead Phoenix Settlement and ensure that its mission carried on after Gandhi’s departure, and he remained in this role for the rest of his life – though he occasionally returned to India for family visits, and in 1930 was one of the original marchers who accompanied Gandhi on the Salt March. Manilal also assumed the role of editor of the Indian Opinion newspaper that was printed at Phoenix Settlement (beginning in 1920).

Manilal married his wife Sushila Gandhi (nee Mashruwala) in 1927, and together they raised their children – Sita, Arun, and Ela – at Phoenix Settlement. There the family lived in “Sarvodaya House” until 1944, when they built a larger house of their own for their growing family, called “Kasturba Bhavan” (named after Manilal’s mother, Kasturba Gandhi). Under Manilal’s leadership, the Phoenix Settlement community engaged in a new round of nonviolent activism at Phoenix Settlement in response to increasing apartheid laws being enacted in South Africa after 1948. Before his death, Manilal actively defied these apartheid rules by entering places demarcated “Whites Only” and by participating in boycotts and other nonviolent acts of the Disobedience Campaign (1952) led by the African National Congress. Manilal was arrested and imprisoned numerous times for this activism. Manilal Gandhi died in 1956, at which time his wife Sushila became the leader of Phoenix Settlement.

Santok Gandhi

Santok Gandhi was born in India, and married at a young age to Maganlal Gandhi, who was Gandhi’s cousin once removed, whom Gandhi often referred to as his nephew. After her husband Maganlal followed Gandhi to South Africa in 1903 for employment opportunities, Santok followed her husband to South Africa in 1904. Later in 1904 Santok and Maganlal moved to Phoenix Settlement, becoming some of the earliest members of Gandhi’s first intentional community. Santok took part in the daily life at Phoenix Settlement, learning to farm and to help operate the printing press. Her children were born at Phoenix Settlement.

In South Africa, Santok and her husband became involved in helping to carry out Gandhi’s nonviolent civil disobedience campaigns. Santok and her children spent some time at Tolstoy Farm, Gandhi’s second intentional community in South Africa, when Maganlal was in prison in Johannesburg for civil disobedience. Santok participated in the Great March for Indians’ civil rights in South Africa in 1913, and was herself sentenced to three months in prison with hard labor.

When Gandhi departed South Africa in 1914, Santok, Maganlal, and their children elected to return to India, where they helped to build Sabarmati Ashram, Gandhi’s third intentional community. Santok and Maganlal took on increasing responsibilities at Sabarmati Ashram, with Maganlal serving as the de facto figure in charge whenever Gandhi was away. Given their orthodox Hindu background, Santok and Maganlal struggled at times with some of the communal values, most notably the effort to remove untouchability and to cohabit with a Dalit family. Santok elected to leave Sabarmati Ashram in 1928, after her husband passed away.

Hermann Kallenbach

Hermann Kallenbach (1871-1945) was born into a large Lithuanian Jewish family. He studied at the Royal School for Architects in Stuttgart, graduating in 1896 with qualifications as a carpenter, mason, and architect. After graduating and completing a year of military service, Kallenbach moved to Johannesburg, South Africa, where he began practicing as an architect, eventually becoming a senior partner in the firm Kallenbach & Reynolds. Kallenbach first met Gandhi in Johannesburg through a mutual friend. In the early years of their acquaintance they met over meals at vegetarian restaurants, and Gandhi persuaded Kallenbach to join him in implementing daily habits of self-discipline, including giving up meat, alcohol, and tobacco, and practicing greater fiscal discipline. When Gandhi was released from prison in 1908, he left his wife and four sons at Phoenix Settlement for the time being, and began to live with Kallenbach in his home in Johannesburg to remain closer to the court and prison as the struggle for Indian civil rights in South Africa continued.

In May of 1910, Kallenbach purchased 1,100 acres of farmland in a rural setting twenty-two miles southwest of Johannesburg, to co-found (along with Gandhi) Tolstoy Farm. A dilapidated farmhouse came with the land, and though it was in dire need of repair, Gandhi and Kallenbach agreed that it was suitable for their immediate habitation while they made improvements to the property in preparation for the arrival of the civil resisters and their families. Gandhi and Kallenbach named the community Tolstoy Farm in honor of Count Leo Tolstoy, for they had each been impacted by his writing. At Tolstoy Farm the residents built upon many of the values and practices from Phoenix Settlement, but they also undertook additional experiments in cohousing, celibacy, farming, dietary restriction, economic self-sufficiency, alternative medicine, home schooling, and multifaith community building as their collective understanding of universal wellbeing continued to evolve.

When Gandhi was preparing to leave South Africa and return to India in 1914, the residents of Tolstoy Farm and Phoenix Settlement had to decide if they wanted to remain in South Africa or move to India with Gandhi. Kallenbach elected to go to India. However, the outbreak of World War I altered the course of Kallenbach’s life. Kallenbach had lived in South Africa for the past eighteen years, but was technically a German citizen. As such, England declared him an “enemy alien,” and he was sent to a detention camp on the British Isle of Man from 1915-1917. After Kallenbach was released in a prisoner exchange in 1917, he decided not to move to India – indeed, he did not travel to India until many years later, visiting Gandhi at Sevagram Ashram in 1937 and 1939 – but instead returned to South Africa. There, he ultimately sold the Tolstoy Farm land and made Johannesburg his home base for professional reasons, resuming his work as an architect and growing increasingly active as a member of the Jewish community there and in the Zionist cause.

Sabarmati Ashram

Gandhi founded Sabarmati Ashram in 1917 near Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. This was Gandhi’s third major intentional community, and his home until he disbanded it in 1933. All residents vowed to uphold eleven observances that the community deemed essential to the pursuit of universal wellbeing (sarvodaya): truth; nonviolence; celibacy; control of the palate; non-stealing; non-possession; physical labor; economic independence; fearlessness; removal of untouchability; and tolerance. Here also residents underwent disciplined training for nonviolent civil resistance, and helped to plan and carry out multiple civil disobedience campaigns. Sabarmati Ashram grew from an initial membership of 25 residents to nearly 300 members at its height.

Vinoba Bhave

Vinoba Bhave (1895-1982) was born in Gagode Budruk, India. From a young age he was a voracious reader with an aptitude for languages, and interest in Hindu philosophy as well as social reform. At the age of twenty he decided to embrace a spiritual path and forego higher education as well as the married life of a householder. In 1916, Bhave arrived at Sabarmati Ashram after reading about Gandhi in the press and briefly exchanging letters. Gandhi invited Bhave to join the community. Bhave initially helped with the education program, and increasingly took on more responsibilities. Gandhi approved of Bhave’s commitment to nonviolence and celibacy, and appreciated his intellectual contributions to the community, enjoying especially their ongoing discussion of the Bhagavad Gita (Bhave eventually published his own translation and commentary on this Hindu text). When Gandhi decided to establish a satellite community of Sabarmati Ashram near Wardha, Maharashtra (India), in 1921, he sent Bhave to manage it.

Bhave worked alongside Gandhi during various anticolonial campaigns, and was imprisoned for his nonviolent civil resistance on multiple occasions. During the Quit India campaign of 1942 Bhave was sent to Yeravda Central Prison, where he served a five-year sentence. Bhave recorded in his memoir that he remained ever ready to fulfill his pledge to fast unto death if Gandhi sent him the order, writing “I would have done it not from knowledge (like Bapu/Gandhi) but from faith. I have no doubt at all that an individual can make such a sacrifice, with the fullest reverence and love, in obedience to an order accepted in faith.”

In the months and years immediately following Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, Bhave managed the day-to-day affairs of Sevagram Ashram, traveling between the Sevagram community and the nearby community that he had founded in Paunar, Maharashtra. In the 1950s, Bhave walked throughout central India on a Bhoodan Yajna, or Land Gift Pilgrimage, persuading landowners to give small plots of farmable land to landless villagers so that they could live rent-free and engage in subsistence farming. In 1959, Bhave gave the Paunar ashram to a small group of women who had joined him in walking on his Land Gift movement, and who wanted to form their own spiritual community (which they called the Brahma Vidya Mandir); Bhave in turn went on to establish several additional ashrams before his death in 1982.

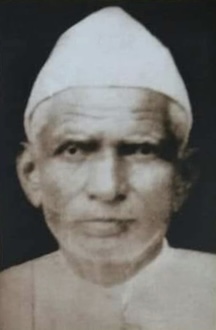

Dudabhai Dafda

Dudabhai Dafda (1889-1964) was born in Botad, India, into a Dalit (“untouchable”) subcaste known as Dhed that is traditionally associated with the occupation of weaving. Dudabhai broke away from this hereditary occupation, however, through his connection with Thakkar Baba (Amritlal Vithaldas Thakkar). Thakkar Baba was a member of the Servants of India Society, and was working in the state of Gujarat to provide basic education to Dalits as part of a caste reform initiative. Dudabhai was a good student, and Thakkar Baba began to train him to teach basic literacy to other Dalits. When Thakkar Baba learned that Gandhi was founding an intentional community in Gujarat in 1915 (which became Sabarmati Ashram), he immediately recommended Dudabhai Dafda and his family to Gandhi as potential residents.

Gandhi put the recommendation that a Dalit family join the Sabarmati Ashram community up for discussion with his current coresidents, who agreed – after significant debate – to admit the family. Thus Dudabhai, along with his wife Danibehn and their young daughter Lakshmi, joined Sabarmati Ashram in September of 1915. Gandhi wanted to expand educational opportunities for Dalits and women as part of the mission of Sabarmati Ashram, and Dudabhai likely welcomed the opportunity to contribute to this work. Dudabhai and Danibehn may have also welcomed the promise of living as equals in a community committed to abolishing untouchability, and raising their young daughter there. However, after joining Sabarmati Ashram they quickly became aware that there was ongoing debate among the residents about untouchability, and that the community was not entirely free from caste prejudice. For instance, Gandhi notes in his autobiography that he detected the women’s “indifference, if not their dislike, towards Danibehn” and that he pleaded with Dudabhai to “swallow minor insults” and ask his wife to do likewise. Gandhi often recounted a story about Dudabhai’s stoic reaction on an occasion when an upper-caste villager physically assaulted Dudhabhai while he was attempting to draw water from the village well. Gandhi took inspiration from Dudabhai’s silent suffering at the hands of the upper-caste villager, praising Dudabhai’s inner strength, discipline, and commitment to nonviolence, and emphasizing that this sort of brave discipline in the face of injustice is what will eventually melt the heart of the oppressor.

In spite of Gandhi praise, Dudabhai and Danibehn, decided to leave Sabarmati Ashram after living there for less than a year. Four years later, however, they returned to leave Lakshmi – then approximately six years old and ready to begin formal schooling – to be raised and educated by the community, as they returned to Dudabhai’s native village of Botad, where he opened a small school for Dalits. Gandhi and Dudabhai corresponded regularly about Lakshmi as she grew up in Sabarmati Ashram, until her eventual marriage and departure from the community in 1933.

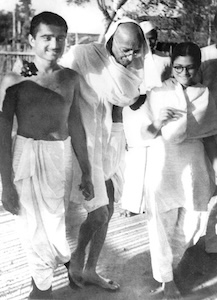

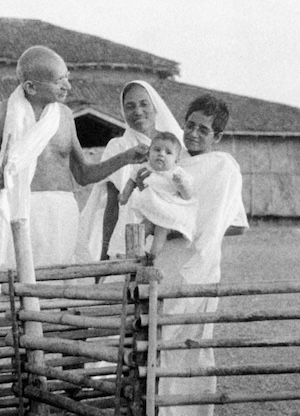

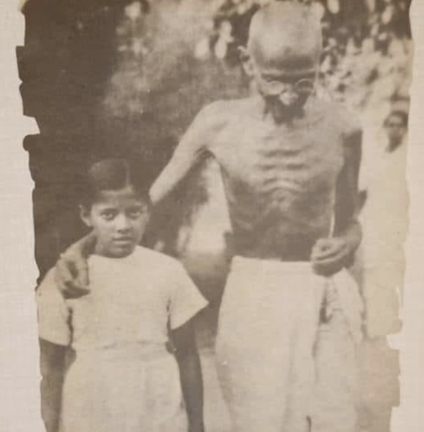

Kanu Gandhi

Kanu Gandhi (1917-1986) was Gandhi’s grandnephew. He was the son of Narandas and Jamuna Gandhi, who lived at Sabarmati Ashram and then at Sevagram Ashram. Kanu’s father, Narandas, served as the de facto manager of Sabarmati Ashram whenever Gandhi was away. Kanu was raised in these intentional communities in India and received his education there. He was trained from his youth in the ideals of universal wellbeing (sarvodaya), nonviolent civil resistance (satyagraha, and he first went to prison in 1932 at the young age of 15), and selfless service (seva). As a young man Kanu became a close aide to Gandhi, and he was frequently found at Gandhi’s side both within the community and also when Gandhi was traveling for political engagements.

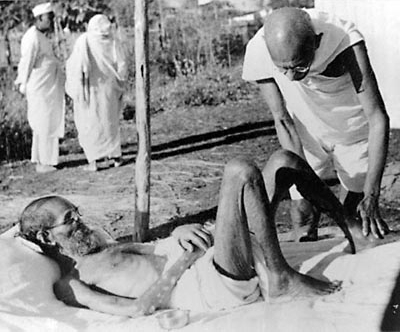

Kanu developed an interest in photography as a young man, though he never received formal training in the photographic arts. For the last decade of Gandhi’s life (from 1938-1948), Kanu captured many intimate and invaluable photos of the communal life at Sevagram Ashram, as well as photos of Gandhi at significant political events and moments. Some of the photos of the residents of Sevagram Ashram that are featured on this archive are the work of Kanu Gandhi, which are now in the public domain.

Kanu married Abha Chatterjee (married name: Abha Gandhi) in 1944, who had lived at Sevagram Ashram from the age of 13. After Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, Kanu and Abha continued to promote the way of life they had learned at Sevagram Ashram in Rajkot, Gujarat, teaching spinning and promoting cottage industries there at Rashtriya Shala. Kanu also continued to practice photography until his death in 1986.

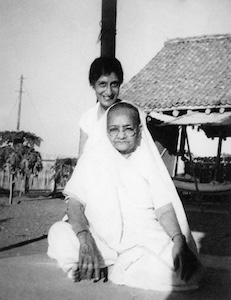

Kasturba Gandhi

Kasturba Gandhi (1869-1944) was born in Porbandar, India. She met Gandhi when they were both young teenagers, in a marriage arranged by their parents. When Gandhi accepted a position in South Africa in 1893, Kasturba initially stayed in India. However, after Gandhi decided that he would stay in South Africa longer than his initial twelve-month contract, Kasturba moved to there to join him. Her first two sons, Harilal and Manilal, were born in India, while her youngest two sons, Ramdas and Devdas, were born in South Africa. In the summer of 1906, Kasturba and her sons moved to join Gandhi and the newspaper press workers at Gandhi’s first intentional community, Phoenix Settlement.

The transition to rural farm life and to a new set of communal rules at Phoenix Settlement was not easy for Kasturba, and she did not always agree with all of the communal rules that Gandhi sought to implement. For instance, Kasturba voiced her skepticism on multiple occasions about the alternative education her sons were receiving in place of attending more accredited educational institutions. Gandhi wrote about some of the disagreements they had in his autobiography as well as in personal correspondence, and occasionally discussed them in his public talks. We have less insight into Kasturba’s mindset, however, as she did not write about her life experiences.

Kasturba was in residence with Gandhi at all of his intentional communities. Although Kasturba and Gandhi remained married until her death in 1944, they practiced celibacy from 1906 forward. Kasturba grew politically active in South Africa, and she elected to participate in the Great March there in pursuit of greater civil rights for Indians. After Kasturba and Gandhi returned to India in 1915, Kasturba continued to participate in nonviolent anticolonial movements, including taking a leading role in the Dharasana Salt satyagraha of 1930 as well as the Quit India satyagraha of 1942. Kasturba received multiple prison sentences for participating in nonviolent civil disobedience movements, beginning with her first imprisonment in South Africa, and ending with her final prison sentence in India during the Quit India campaign. Kasturba died in the Aga Khan Palace prison in 1944.

Maganlal Gandhi

Maganlal Gandhi (1883-1928) was born in India. He was Gandhi’s cousin once removed (the son of Gandhi’s older cousin Kushalbhai Gandhi), although Gandhi often referred to Maganlal his nephew. As a young man Maganlal went to South Africa in 1903 for employment opportunities, following in Gandhi’s footsteps, and initially worked in a merchant’s shop in Tongaat township (near Durban) and then at a branch store in Stanger township. In 1904, when Gandhi was establishing his first community, he invited Maganlal to join Phoenix Settlement. Maganlal was among the first residents to join the Phoenix community, and brought his wife Santok from India to join him in residence there. Their children were born at Phoenix Settlement.

Maganlal embraced life at Phoenix Settlement. He was a hard worker, and quickly began to contribute to the printing press work in order to publish the Indian Opinion weekly newspaper, as well as farming work. Maganlal also embraced Gandhi’s experiments, and while living at Phoenix Settlement he made vows to practice nonviolence and celibacy. As the residents of Phoenix Settlement and Tolstoy Farm grew more involved in anticolonial political campaigns, Gandhi increasingly looked to Maganlal to keep Phoenix Settlement, and Indian Opinion newspaper, operational while he and other residents were imprisoned for civil disobedience.

When Gandhi departed South Africa in 1914, Maganlal, Santok, and their children elected to return to India, where they helped to build Sabarmati Ashram, Gandhi’s third intentional community. Maganlal and Santok took on increasing responsibilities at Sabarmati Ashram, with Maganlal serving as the de facto figure in charge whenever Gandhi was away. Given their orthodox Hindu background, Santok and Maganlal struggled at times with some of the communal values, most notably the effort to remove untouchability and to cohabit with a Dalit family. When Maganlal passed away suddenly from pneumonia in 1928, Gandhi mourned his passing deeply, describing Maganlal in his obituary as the “watchdog” of Sabarmati Ashram in its material, moral, and spiritual aspects, and as dearer to him than his own sons.

Manilal Gandhi

Manilal Gandhi (1892-1956) was born in Rajkot, India. He was the second of four sons born to Gandhi and Kasturba. Manilal moved from India to South Africa as a child to join his father, where he was raised and educated at Phoenix Settlement and Tolstoy Farm. From an early age Gandhi began training Manilal and his elder brother Harilal to lead civil disobedience movements, and also prepared them to spend time in prison for anticolonial activism. In 1910, at the age of 17, Manilal served a three-month prison sentence with hard labor, his first imprisonment for civil disobedience. Gandhi praised Manilal for this, and upheld him as an example for the other children living in the community to emulate. Gandhi also praised Manilal and Harilal in his Indian Opinion newspaper, encouraging others to follow in their footsteps and flood the jails in protest of the discriminatory Asiatic Registration Act.

Whereas Harilal rebelled and left Gandhi’s communities, Manilal by contrast dedicated his life to Gandhi’s communities, and particularly Phoenix Settlement. Manilal returned to India with his parents when they departed South Africa, and lived with the Sabarmati Ashram community in India from 1915-1917. In 1917, Manilal returned to South Africa to lead Phoenix Settlement and ensure that its mission carried on after Gandhi’s departure, and he remained in this role for the rest of his life – though he occasionally returned to India for family visits, and in 1930 was one of the original marchers who accompanied Gandhi on the Salt March. Manilal also assumed the role of editor of the Indian Opinion newspaper that was printed at Phoenix Settlement (beginning in 1920).

Manilal married his wife Sushila Gandhi (nee Mashruwala) in 1927, and together they raised their children – Sita, Arun, and Ela – at Phoenix Settlement. There the family lived in “Sarvodaya House” until 1944, when they built a larger house of their own for their growing family, called “Kasturba Bhavan” (named after Manilal’s mother, Kasturba Gandhi). Under Manilal’s leadership, the Phoenix Settlement community engaged in a new round of nonviolent activism at Phoenix Settlement in response to increasing apartheid laws being enacted in South Africa after 1948. Before his death, Manilal actively defied these apartheid rules by entering places demarcated “Whites Only” and by participating in boycotts and other nonviolent acts of the Disobedience Campaign (1952) led by the African National Congress. Manilal was arrested and imprisoned numerous times for this activism. Manilal Gandhi died in 1956, at which time his wife Sushila became the leader of Phoenix Settlement.

Santok Gandhi

Santok Gandhi was born in India, and married at a young age to Maganlal Gandhi, who was Gandhi’s cousin once removed, whom Gandhi often referred to as his nephew. After her husband Maganlal followed Gandhi to South Africa in 1903 for employment opportunities, Santok followed her husband to South Africa in 1904. Later in 1904 Santok and Maganlal moved to Phoenix Settlement, becoming some of the earliest members of Gandhi’s first intentional community. Santok took part in the daily life at Phoenix Settlement, learning to farm and to help operate the printing press. Her children were born at Phoenix Settlement.

In South Africa, Santok and her husband became involved in helping to carry out Gandhi’s nonviolent civil disobedience campaigns. Santok and her children spent some time at Tolstoy Farm, Gandhi’s second intentional community in South Africa, when Maganlal was in prison in Johannesburg for civil disobedience. Santok participated in the Great March for Indians’ civil rights in South Africa in 1913, and was herself sentenced to three months in prison with hard labor.

When Gandhi departed South Africa in 1914, Santok, Maganlal, and their children elected to return to India, where they helped to build Sabarmati Ashram, Gandhi’s third intentional community. Santok and Maganlal took on increasing responsibilities at Sabarmati Ashram, with Maganlal serving as the de facto figure in charge whenever Gandhi was away. Given their orthodox Hindu background, Santok and Maganlal struggled at times with some of the communal values, most notably the effort to remove untouchability and to cohabit with a Dalit family. Santok elected to leave Sabarmati Ashram in 1928, after her husband passed away.

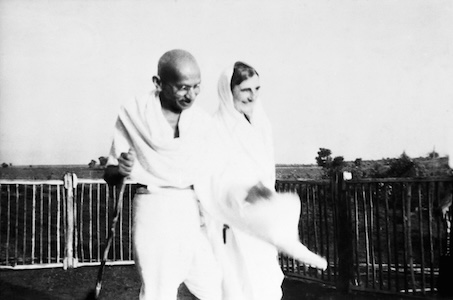

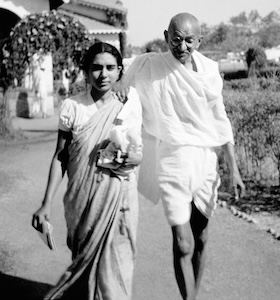

Mirabehn (Madeleine Slade)

Mirabehn’s birth name was Madeleine Slade (1892-1982). She was originally from England, and was the daughter of Sir Edmond Slade, a Royal Navy officer who served as Director of the Naval Intelligence. She first learned of Gandhi from her friend Romain Rolland, the French author who wrote a biography of Gandhi in 1924. Slade read Rolland’s biography and felt called to Gandhi, writing in her memoir The Spirit’s Pilgrimage (published in 1960), “The call was absolute, and that was all that mattered.” Slade wrote to Gandhi, who invited her to come and join him. In 1925, Slade gave away her possessions, said goodbye to her family, and arrived in India.

Gandhi embraced Madeleine Slade as both a coresident and a spiritual co-seeker. Madeleine Slade became known as Mirabehn, the name that Gandhi affectionately bestowed upon her. Mirabehn first lived at Sabarmati Ashram with Gandhi, and then at Sevagram Ashram. At Sabarmati Ashram, Mirabehn began to study Hindi and Gujarati languages, and joined the life of the community by taking turns on sanitation duty, learning to cook Indian meals, spinning cotton, and joining group prayer sessions. During these years at Sabarmati Ashram, Mirabehn grew increasingly active in the Indian freedom struggle. When the Salt Satyagraha began in 1930, Mirabehn took part in the civil disobedience movement. She accompanied Gandhi to the second Round Table Conference in London (1931); was imprisoned for civil disobedience (1932-33); and wrote news essays and traveled to England and the United States to meet dignitaries and make the case for India’s freedom (1934).

Mirabehn was instrumental to the founding of Sevagram Ashram, Gandhi’s final intentional community. It was Mirabehn who initially went to live in Segaon village, which was later renamed Sevagram Ashram, seeking (at Gandhi’s suggestion) to teach the villagers methods of sanitation as well as spinning. When Mirabehn fell ill and could not continue this constructive work, Gandhi came to take her place. Eventually, a new community arose around Gandhi and the villagers as more volunteers came to join Gandhi there. Gandhi particularly admired Mirabehn’s skill in building simple huts out of local materials. This skill can still be observed at Bapu Kuti (Gandhi’s Cottage), which has been preserved at Sevagram Ashram. Mirabehn remained active in the freedom struggle while living at Sevagram Ashram. Gandhi sent her to organize nonviolent Quit India protests in eastern India in 1942, and she was eventually arrested and imprisoned. Mirabehn remained in India for a dozen years after the nation attained independence, where she continued to engage in constructive work in villages until 1959. She then moved to Austria in 1960 for her retirement, where she continued to live a simple life.

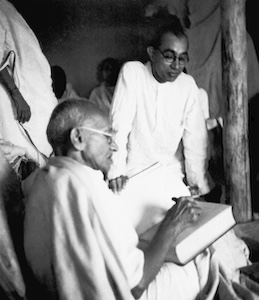

Pyarelal Nayar

Pyarelal Nayar (1899-1982) was born in Kunjah, India (now a part of Pakistan). Pyarelal first saw Gandhi give a talk when he was a college student and attended a meeting of the Indian National Congress in 1919. The next year, Pyarelal decided to quit graduate school (he had been studying for his Master’s degree in English literature at Government College, Lahore) to join the Noncooperation Movement. The Noncooperation Movement, which was led by Gandhi from 1920-1922, was a nonviolent anticolonial campaign wherein Gandhi asked his fellow Indian citizens to boycott colonial rule by refusing to buy imported British products and by withdrawing from colonial-run schools and positions of employment.

Pyarelal was drawn to Gandhi’s nonviolent activism and his idealism, and he soon joined the Sabarmati Ashram community. While living there, Pyarelal was increasingly incorporated into Gandhi’s inner circle. In 1930, when Gandhi launched the Salt March from Sabarmati Ashram, Pyarelal was one of the seventy-eight residents who was selected to march at Gandhi’s side throughout the nonviolent march and to help lead the protest. He was eventually arrested in this protest; and indeed, Pyarelal served time in jail in this and every later satyagraha movement that Gandhi led.

Pyarelal Nayar also lived at Sevagram Ashram. During these years he continued to serve as a close aide to Gandhi, and became one of Gandhi’s personal secretaries. His professional duties in this role entailed keeping a record of all of Gandhi’s correspondence and talks, as well as copyediting his writing; he also engaged in personal service of Gandhi such as cooking and cleaning for him. Pyarelal spent a total of twenty-seven years living with Gandhi. After Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, Pyarelal remained devoted to him, spending the next several decades writing a multi-volume biography of Gandhi, among other works.

Henry Polak

Henry Polak (1882-1959) was originally from Dover, England. He first came to South Africa in 1903, and worked as a journalist on the editorial staff of The Transvaal Critic newspaper. Polak met Gandhi at a gathering of a vegetarian society in Johannesburg in March of 1904. Shortly after meeting Gandhi, Polak also began to work as a freelance writer for Gandhi’s newspaper, Indian Opinion, and grew increasingly involved in the “Indian Question” – the question of Indian civil rights in South Africa. Gandhi also persuaded Polak to study law, and then hired him to work in his law firm in Johannesburg.

In September 1904, Gandhi needed to make a trip from Johannesburg to Durban, where Indian Opinion was published, in order to deal with some financial affairs for the newspaper. As Gandhi boarded the overnight train for this trip, Polak gave him a copy of John Ruskin’s essay “Unto This Last” to read, suggesting that Gandhi might also find it interesting. Reading this essay was a transformative moment in Gandhi’s life, and sparked the idea for establishing his first intentional community, Phoenix Settlement, later that same year.

Polak married Millie Graham Polak (nee Downs), in 1905, with Gandhi serving as Polak’s best man during the wedding ceremony. Initially after their marriage, Henry lived half time at Phoenix Settlement with Gandhi and the other press workers, and travelled back and forth regularly between Phoenix Settlement and Johannesburg, while Millie remained in Johannesburg where she lived with Gandhi’s wife and children and became their teacher. In 1906, Millie moved to Phoenix Settlement to join Henry there, though she decided to return to Johannesburg after just two months. Henry, on the other hand, continued to split his time between Johannesburg and Phoenix Settlement for over a decade, working both on the Indian Opinion newspaper while at Phoenix Settlement, and also in his legal capacity out of Gandhi’s Johannesburg law office. After Gandhi had departed South Africa to return to India (in 1914), Henry and Millie Polak elected to go to India and lived briefly with him at Sabarmati Ashram, before returning to England.

Millie Graham Polak

Millie Graham Polak (nee Downs, 1881-1962) was originally from England. She had met her future husband, Henry Polak, at the London Ethical Society prior to Henry’s move to South Africa in 1903. After Henry to proposed to her, Millie moved from London to Johannesburg to join Henry, where they were married in 1905. Initially after their marriage, Millie lived in Johannesburg at the Gandhi household, where she took on the role of teacher to the Gandhi children. Henry, meanwhile, lived half time at Phoenix Settlement with Gandhi and the other press workers, and travelled back and forth regularly between Phoenix Settlement and Johannesburg.

In the summer of 1906, when Gandhi decided to shift his whole household to Phoenix Settlement, Millie relocated to the new intentional community with the Gandhi family. In her book Mr. Gandhi: The Man (published in 1931), Millie provides a vivid description of Phoenix Settlement at the time of her arrival, emphasizing that “the colony was to be as much as possible self-supporting, and life’s material requirements were to be reduced to a minimum,” and recalling that she was “disappointed and depressed” by her first view of the intentional community.

After just two months at Phoenix Settlement, Millie decided to leave and returned to the Gandhi house in Johannesburg, preferring a more urban setting over the rural farm life. Henry, on the other hand, had a greater fondness for Phoenix Settlement and continued to split his time between it and Johannesburg for over a decade. During these years Millie continued to aid the Gandhi family and support Gandhi’s causes from her Johannesburg location. After Gandhi had departed South Africa to return to India (in 1914), Millie and Henry Polak elected to go to India and lived briefly with him at Sabarmati Ashram, before returning to England.

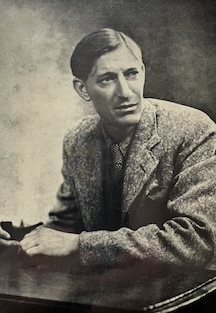

Reginald Reynolds

Reginald Reynolds (1905-1958) was born in Glastonbury, England. He was raised in a Quaker family and educated at Quaker institutions, including Friends School in Essex and Woodbrooke College in Birmingham. As a young pacifist with anticolonial leanings, Reginald was drawn to Gandhi’s teachings, and after exchanging letters with Gandhi, Reginald left his home to embark upon the journey to join Gandhi at Sabarmati Ashram. Reginald arrived at Sabarmati Ashram in 1929, at the age of 24, and recorded in his journal that he was joining the community for an “indefinite duration” and with “a determination to make amends, so far as one person could do so, for all the degradation that Indians had suffered from the British.”

At Sabarmati Ashram, Reginald began to study Hindi and Sanskrit languages, and joined the life of the community by learning to spin cotton, working in the fields, taking turns on sanitation duty, cooking duty, and at other daily chores, and participating in the ecumenical group prayer sessions. While at Sabarmati Ashram, Reginald grew increasingly active in the Indian freedom struggle. When the Salt Satyagraha civil disobedience movement began in 1930, Reginald was eager to participate. Gandhi selected only Indian coresidents to join him on the Salt March, but asked Reginald if he would participate in a different way: Gandhi dispatched Reginald to hand deliver a letter to the British Viceroy, Lord Irwin, informing him of the terms of the Salt March, and stating that in order to demonstrate that he did not consider the British as enemies he was having the letter “specially delivered by a young English friend who believes in the Indian cause and is a full believer in nonviolence.” Gandhi also asked that Reginald not court imprisonment during the Salt Satyagraha, so that he could be available to help edit and publish his newspaper Young India if needed during the movement as more and more coresidents were arrested.

As Reginald faced ongoing health challenges in India, he ultimately decided to return to England in the summer of 1930, determined to there continue to advocate for the cause of Indian independence from colonial rule. Reginal Reynolds remained dedicated to the ethics of nonviolence throughout his lifetime, and was a conscientious objector to World War II. When his health permitted he undertook significant travels, returning to India once again after its independence. He authored several books about his travels and his views on global politics and culture.

Amtul Salaam

Amtul Salaam (1907-1985, also known as Bibi Amtus Salam) was born in Patiala, India. Raised in an aristocratic and conservative Muslim family, she observed purdah and did not receive a formal education. As a young woman she was drawn to politics, perhaps through the influence of an elder brother. By 1931, at the age of 24, she decided to leave home behind and moved to Sabarmati Ashram. Amtul was drawn to Gandhi’s teachings about the need for Hindu-Muslim unity in the struggle for India’s independence. Gandhi insisted that Amtul should study while living at Sabarmati Ashram to make up for her lack of formal education, and encouraged her to improve her Urdu reading and writing skills, as well as study the Quran. Amtul also learned spinning and participated in the labor of everyday life (cooking, cleaning, farming, etc.) at the community. Amtul regularly suffered from bouts of malaria and other ailments while in residence at Sabarmati Ashram, and though she was a strong advocate of nature cure, she often had to leave for medical attention beyond what could be provided by Gandhi and others living at the ashram.

After Gandhi had disbanded Sabarmati Ashram and settled at his final intentional community, Sevagram Ashram, Amtul joined him there. She resided at times at Sevagram Ashram during Gandhi’s years there, and at times Gandhi sent her to various Dalit colonies to engage in service work in the effort to abolish untouchability. While at Sevagram Ashram, Amtul was one of Gandhi’s partners in his controversial experiments in celibate sexuality. Whenever Amtul was away, whether for service work, medical attention, or in jail for civil disobedience, she and Gandhi regularly wrote letters to one another. Their correspondence reveals a somewhat tumultuous relationship, with Gandhi often expressing paternal affection for Amtul, and also frequently expressing exasperation with her for being too suspicious of him and other coresidents.

When colonial India gained its independence in 1947 and India and Pakistan were partitioned into two countries, Hindu-Muslim riots flared across South Asia. Amtul accompanied Gandhi as he traveled to Bengal to try to restore peace there, and she undertook a fast for 21 days to promote Hindu-Muslim unity. Amtul elected to remain in India after independence, even as her family moved to Pakistan. After Gandhi’s death, Amtul continued to promote Hindu-Muslim unity, founding the Kasturba Seva Mandir in Rajpura, Punjab to help displaced refugees and promote to way of life she had learned at Sabarmati Ashram and Sevagram Ashram.

Lakshmi Dafda Sharma

Lakshmi Sharma (nee Dafda, 1914-1984) was born to Dudabhai and Danibehn Dafda. As members of a Dalit (“untouchable”) subcaste, the Dafda family was ascribed to the bottom of the caste hierarchy. In September of 1915, when Lakshmi was just a young toddler, the Dafda family joined Sabarmati Ashram at Gandhi’s invitation. Gandhi has been introduced to the family through a colleague, Thakkar Baba, who was engaged in anti-caste work through the Servants of India Society, and who encouraged Gandhi and his coresidents to consider how Sabarmati Ashram could be more proactive in contributing to the effort to abolish untouchability. The arrival of the Dafda family challenged upper-caste residents of Sabarmati Ashram to think through their commitment to inclusivity and equity. As the residents wrestled with practical questions of day-to-day life in a mixed caste community, such as whether a commitment to equity also entailed intercaste dining, the Dafda family decided to leave just nine months later.

But when Lakshmi was 6 years old, Dudabhai and Danibehn brought her back to Sabarmati Ashram. They gave up their parental rights, and in exchange Gandhi promised to raise Lakshmi as his “adopted” daughter, educating her and treating her as equal to the other children. Lakshmi grew up at Sabarmati Ashram under the care of Gandhi and his wife Kasturba and other senior residents. Gandhi spoke often about his efforts to educate and “refine” Lakshmi, seeking to mold her into a model Dalit. In her teenage years, Lakshmi did not always act as Gandhi wanted her to. In letters to her father, Gandhi complained that she indulged in “pranks,” that she could not “control her mind,” and that she disobeyed the community’s rules.

When Lakshmi was 19, Gandhi arranged her marriage to a young upper-caste man named Maruti Sharma. The wedding, which took place in 1933, defied the orthoprax norm that Dalits only marry other Dalits. After the wedding, Lakshmi left Sabarmati Ashram for good, moving to her husband’s village, where she became the mother of two children.

Sevagram Ashram

Gandhi founded Sevagram Ashram in 1936 in Segaon Village, Maharashtra, India. This was Gandhi’s final experiment with utopia, and his home from 1936 until his death in 1948. Seagon Village was located in rural central India, and had a mixed caste population of approximately 600 residents, a majority of whom were Dalits (“untouchables”). Membership at this community fluctuated, but everyone joining Sevagram Ashram was expected to undertake service work in the village, such as shoveling excrement, growing vegetables, and spinning. A subset of residents who were young and female were also expected to engage in selfless service through participation in Gandhi’s controversial experiments with celibate sexuality. Eventually, Gandhi also called upon his coresidents to engage in selfless service for the nation of India, culminating in the Quit India anticolonial campaign.

Vinoba Bhave

Vinoba Bhave (1895-1982) was born in Gagode Budruk, India. From a young age he was a voracious reader with an aptitude for languages, and interest in Hindu philosophy as well as social reform. At the age of twenty he decided to embrace a spiritual path and forego higher education as well as the married life of a householder. In 1916, Bhave arrived at Sabarmati Ashram after reading about Gandhi in the press and briefly exchanging letters. Gandhi invited Bhave to join the community. Bhave initially helped with the education program, and increasingly took on more responsibilities. Gandhi approved of Bhave’s commitment to nonviolence and celibacy, and appreciated his intellectual contributions to the community, enjoying especially their ongoing discussion of the Bhagavad Gita (Bhave eventually published his own translation and commentary on this Hindu text). When Gandhi decided to establish a satellite community of Sabarmati Ashram near Wardha, Maharashtra (India), in 1921, he sent Bhave to manage it.

Bhave worked alongside Gandhi during various anticolonial campaigns, and was imprisoned for his nonviolent civil resistance on multiple occasions. During the Quit India campaign of 1942 Bhave was sent to Yeravda Central Prison, where he served a five-year sentence. Bhave recorded in his memoir that he remained ever ready to fulfill his pledge to fast unto death if Gandhi sent him the order, writing “I would have done it not from knowledge (like Bapu/Gandhi) but from faith. I have no doubt at all that an individual can make such a sacrifice, with the fullest reverence and love, in obedience to an order accepted in faith.”

In the months and years immediately following Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, Bhave managed the day-to-day affairs of Sevagram Ashram, traveling between the Sevagram community and the nearby community that he had founded in Paunar, Maharashtra. In the 1950s, Bhave walked throughout central India on a Bhoodan Yajna, or Land Gift Pilgrimage, persuading landowners to give small plots of farmable land to landless villagers so that they could live rent-free and engage in subsistence farming. In 1959, Bhave gave the Paunar ashram to a small group of women who had joined him in walking on his Land Gift movement, and who wanted to form their own spiritual community (which they called the Brahma Vidya Mandir); Bhave in turn went on to establish several additional ashrams before his death in 1982.

Abha Gandhi

Abha Gandhi (1927-1995, nee Chatterjee) came to live at Sevagram Ashram in 1939 or 1940, at the age of 12 or 13. She and several of her siblings were brought there by her father, Amrita Lal Chatterjee, who read about Gandhi in the news and came from Bengal to join Sevagram Ashram and engage in the constructive work program there. Although Amrita Lal eventually returned to Bengal, Abha remained and received her education in the alternative school that had been set up in the community. There she was trained in the ideals of universal wellbeing (sarvodaya) and selfless service (seva). As a young woman Abha became a close aide to Gandhi, and she was also one of Gandhi’s partners in his controversial experiments in celibate sexuality.

Abha married Kanu Gandhi, Gandhi’s grandnephew and a fellow resident of Sevagram Ashram, in 1944. The marriage took place after a prolonged engagement due both to Abha’s status as a minor, and also to some resistance from Abha’s family over the idea of her marrying someone from outside her caste and region. When the wedding eventually took place it was with the consent of Abha and Kanu, their parents, and Gandhi and Kasturba – although Gandhi insisted that they must continue to observe celibacy while they lived at Sevagram Ashram.

Abha was at Gandhi’s side when he was assassinated in New Delhi on January 30, 1948. After Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, Abha and Kanu continued to promote the way of life they had learned at Sevagram Ashram in Rajkot, Gujarat, teaching spinning and promoting cottage industries there at Rashtriya Shala.

Kanu Gandhi

Kanu Gandhi (1917-1986) was Gandhi’s grandnephew. He was the son of Narandas and Jamuna Gandhi, who lived at Sabarmati Ashram and then at Sevagram Ashram. Kanu’s father, Narandas, served as the de facto manager of Sabarmati Ashram whenever Gandhi was away. Kanu was raised in these intentional communities in India and received his education there. He was trained from his youth in the ideals of universal wellbeing (sarvodaya), nonviolent civil resistance (satyagraha, and he first went to prison in 1932 at the young age of 15), and selfless service (seva). As a young man Kanu became a close aide to Gandhi, and he was frequently found at Gandhi’s side both within the community and also when Gandhi was traveling for political engagements.

Kanu developed an interest in photography as a young man, though he never received formal training in the photographic arts. For the last decade of Gandhi’s life (from 1938-1948), Kanu captured many intimate and invaluable photos of the communal life at Sevagram Ashram, as well as photos of Gandhi at significant political events and moments. Some of the photos of the residents of Sevagram Ashram that are featured on this archive are the work of Kanu Gandhi, which are now in the public domain.

Kanu married Abha Chatterjee (married name: Abha Gandhi) in 1944, who had lived at Sevagram Ashram from the age of 13. After Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, Kanu and Abha continued to promote the way of life they had learned at Sevagram Ashram in Rajkot, Gujarat, teaching spinning and promoting cottage industries there at Rashtriya Shala. Kanu also continued to practice photography until his death in 1986.

Kasturba Gandhi

Kasturba Gandhi (1869-1944) was born in Porbandar, India. She met Gandhi when they were both young teenagers, in a marriage arranged by their parents. When Gandhi accepted a position in South Africa in 1893, Kasturba initially stayed in India. However, after Gandhi decided that he would stay in South Africa longer than his initial twelve-month contract, Kasturba moved to there to join him. Her first two sons, Harilal and Manilal, were born in India, while her youngest two sons, Ramdas and Devdas, were born in South Africa. In the summer of 1906, Kasturba and her sons moved to join Gandhi and the newspaper press workers at Gandhi’s first intentional community, Phoenix Settlement.

The transition to rural farm life and to a new set of communal rules at Phoenix Settlement was not easy for Kasturba, and she did not always agree with all of the communal rules that Gandhi sought to implement. For instance, Kasturba voiced her skepticism on multiple occasions about the alternative education her sons were receiving in place of attending more accredited educational institutions. Gandhi wrote about some of the disagreements they had in his autobiography as well as in personal correspondence, and occasionally discussed them in his public talks. We have less insight into Kasturba’s mindset, however, as she did not write about her life experiences.

Kasturba was in residence with Gandhi at all of his intentional communities. Although Kasturba and Gandhi remained married until her death in 1944, they practiced celibacy from 1906 forward. Kasturba grew politically active in South Africa, and she elected to participate in the Great March there in pursuit of greater civil rights for Indians. After Kasturba and Gandhi returned to India in 1915, Kasturba continued to participate in nonviolent anticolonial movements, including taking a leading role in the Dharasana Salt satyagraha of 1930 as well as the Quit India satyagraha of 1942. Kasturba received multiple prison sentences for participating in nonviolent civil disobedience movements, beginning with her first imprisonment in South Africa, and ending with her final prison sentence in India during the Quit India campaign. Kasturba died in the Aga Khan Palace prison in 1944.

Manu Gandhi

Manu Gandhi (1927-1969) was Gandhi’s grandniece. She was the youngest of four daughters born to Jaisukhlal Amritlal Gandhi, who was Gandhi’s nephew, and his wife Kasumba. Manu joined Sevagram Ashram, Gandhi’s final intentional community, at the age of fourteen in early 1942, having been brought there by her father (her mother had passed away in 1939). At Sevagram Ashram, Manu began to study at the community school, and was trained in the communal ideology of seva, selfless service.

Later in 1942 the Quit India anticolonial movement was launched from Sevagram Ashram. Though just a teenager, Manu joined this civil disobedience movement, and was arrested and imprisoned. Initially imprisoned in Nagpur Central Jail, she was transferred after nine months to the Aga Khan Palace prison where Gandhi had been imprisoned along with Kasturba and several other leaders of the movement. Gandhi was then weakened from fasting, and Kasturba was ill, and so Manu was transferred there so that she could serve Gandhi and Kasturba while carrying out her prison sentence. When not nursing Kasturba or Gandhi, she continued her education with Gandhi and the other residents of the Aga Khan Palace prison.

After Manu was released from prison in May 1944, she was at Gandhi’s side for his remaining years until his death in 1948, accompanying him at Sevagram Ashram and also when he traveled. During these years Manu helped to record some of Gandhi’s correspondence and speeches. She was also one of Gandhi’s partners in his controversial experiments in celibate sexuality. Manu was at Gandhi’s side when he was assassinated in New Delhi on January 30, 1948. After Gandhi’s death, she worked for the Ministry of Education and traveled throughout India visiting schools to teach about Gandhi’s life and message. She died from tuberculosis in 1969.

Amrit Kaur

Amrit Kaur (1887-1964, also known as Rajkumari Amrit Kaur) was born in Lucknow, India. She was educated in England, and completed college at Oxford University in 1918. After returning to India she first met Gandhi in Mumbai (Bombay) in 1919, and was drawn to his nonviolent politics. Kaur worked as one of Gandhi’s secretaries for sixteen years beginning in 1930, and during this time she grew increasingly involved in the independence movement. Kaur joined the Indian National Congress, co-founded the All-India Women’s Conference and served as its president in 1933, and advocated for many women’s rights issues throughout her lifetime.

Kaur joined Sevagram Ashram, Gandhi’s final intentional community. There she left her upper-class lifestyle behind, and embraced vows of voluntary poverty, celibacy (she never married nor had children), and service for the greater good. Because Kaur was committed to this lifestyle and had taken a lifelong vow of nonviolence, Gandhi entrusted her with significant tasks as he planned civil disobedience campaigns. Most notably, Gandhi sent Kaur to organize nonviolent Quit India protests in northern India in 1942, and she was beaten at one protest in Shimla by the colonial police and then arrested. She was discharged from prison after two months, due to the severity of her weight loss, and placed under house arrest in Shimla for the remainder of her three-year sentence. Kaur and Gandhi exchanged frequent and often very candid letters with one another when they were not in residence together.

Kaur left her residence at Sevagram Ashram around the time of India’s independence in order to serve the nation. Leading up to India’s independence in 1947, Kaur served on the Constituent Assembly of India, the working group that framed the Constitution of India. When India gained its independence, Amrit Kaur was appointed the first Health Minister of India, a position she served in from 1947-1957.

Mirabehn (Madeleine Slade)

Mirabehn’s birth name was Madeleine Slade (1892-1982). She was originally from England, and was the daughter of Sir Edmond Slade, a Royal Navy officer who served as Director of the Naval Intelligence. She first learned of Gandhi from her friend Romain Rolland, the French author who wrote a biography of Gandhi in 1924. Slade read Rolland’s biography and felt called to Gandhi, writing in her memoir The Spirit’s Pilgrimage (published in 1960), “The call was absolute, and that was all that mattered.” Slade wrote to Gandhi, who invited her to come and join him. In 1925, Slade gave away her possessions, said goodbye to her family, and arrived in India.

Gandhi embraced Madeleine Slade as both a coresident and a spiritual co-seeker. Madeleine Slade became known as Mirabehn, the name that Gandhi affectionately bestowed upon her. Mirabehn first lived at Sabarmati Ashram with Gandhi, and then at Sevagram Ashram. At Sabarmati Ashram, Mirabehn began to study Hindi and Gujarati languages, and joined the life of the community by taking turns on sanitation duty, learning to cook Indian meals, spinning cotton, and joining group prayer sessions. During these years at Sabarmati Ashram, Mirabehn grew increasingly active in the Indian freedom struggle. When the Salt Satyagraha began in 1930, Mirabehn took part in the civil disobedience movement. She accompanied Gandhi to the second Round Table Conference in London (1931); was imprisoned for civil disobedience (1932-33); and wrote news essays and traveled to England and the United States to meet dignitaries and make the case for India’s freedom (1934).