Mexican Folk Pottery

Editorial Statement

The Aesthetics of Oppression

Is There a Feminine Aesthetic?

Quilt Poem

Women Talking, Women Thinking

The Martyr Arts

The Straits of Literature and History

Afro-Carolinian "Gullah" Baskets

The Left Hand of History

Weaving

Political Fabrications: Women's Textiles in Five Cultures

Art Hysterical Notions of Progress and Culture

Excerpts from Women and the Decorative Arts

The Woman's Building

Ten Ways to Look at a Flower

Trapped Women: Two Sister Designers, Margaret and Frances MacDonald

Adelaide Alsop Robineau: Ceramist from Syracuse

Women of the Bauhaus

Portrait of Frida Kahlo as a Tehuana

Feminism: Has It Changed Art History?

Are You a Closet Collector?

Making Something From Nothing

Waste Not/Want Not: Femmage

Sewing With My Great-Aunt Leonie Amestoy

The Apron: Status Symbol or Stitchery Sample?

Conversations and Reminiscences

Grandma Sara Bakes

Aran Kitchens, Aran Sweaters

Nepal Hill Art and Women's Traditions

The Equivocal Role of Women Artists in Non-Literate Cultures

Women's Art in Village India

Pages from an Asian Notebook

Quill Art

Turkmen Women, Weaving and Cultural Change

Kongo Pottery

Myth and the Sexual Division of Labor

Recitation of the Yoruba Bride

"By the Lakeside There Is an Echo": Towards a History of Women's Traditional Arts

Bibliography

Carolyn Berry

Quillwork, the decoration of animal skins with dyed and natural porcupine quills, was unique to North American Indian culture and practiced only by women. This art form probably originated in the Great Lakes area and the surrounding woodlands. As white invasion and colonization intensified, the various tribes of corn farmers originally inhabiting the area migrated west to the Plains where eventually their culture centered on buffalo hunting. The Cheyenne were one such tribe who brought with them women's ancient art of quillwork.

A balance of power existed within Cheyenne society. Chiefs were men, but there were memories of women's holding this position. Cheyenne society was matrilineal. Women owned the tipis in which they lived with their husband, daughters, daughters' husbands and unmarried sons. A wealthy man could have more than one wife; frequently sisters married the same man. If the first wife didn't approve of her husband's choice she could divorce him, although she might commit suicide (by hanging herself with her braids). Chastity was highly honored; girls and women wore the chastity rope. Seduction and rape were extremely rare (as was murder). Girls' puberty was celebrated ritually, and women maintained their own societies, traditions, religious beliefs and secular position. Sharing of work by women made possible the long hours necessary for such a precise and painstaking art as quillwork.

Quills, obtained from porcupines which the men hunted, were removed promptly, sorted into different sizes and stored in bladder bags. The largest and coarsest quills, taken from the tail, were used in broad masses of embroidery. Medium quills came from the back of the animal and small ones from the neck. The finest were taken from the belly and were used for "the most delicate lines so noticeable in the exquisite work to be found in early specimens."

After sorting, the quills were boiled with natural dyes usually found locally, although Cheyenne would travel great distances to find plants needed for particular colors. Dye stuffs included moss, stones, buffalo-berries, wild grapes, cattails, oak bark and many other barks, flowers and seeds. The ingredients and process were often kept secret. Eventually quills were colored with commercial dyes or soaked with dyed trade cloth.

Quills were sewn onto skins tanned by the women; in this process, many days long, the skin was stretched, scraped, bleached, softened and stretched once again. Tanning tools were handed down by women from generation to generation. After tanning the skins, the woman would cut and shape the leather into the object she intended to embroider with quills.

As she worked, the woman held a supply of quills in her mouth to soften them so they could be flattened. Since they would split if punctured, quills were held to the skin between rows of stitches or with a stitch over each quill. Sinew, dried black grass and fine roots were used for sewing. The sinew thread was kept moist except for one end, which was licked, twisted and let dry to stiffen. This was then threaded through holes made in the hide with an awl. Extra sewing supplies were carried in a quill-decorated purse trappers called possible-sacks, in which women also kept small ornaments, medicine, counters for gambling, plum stones for the seed game and clothes for small children.

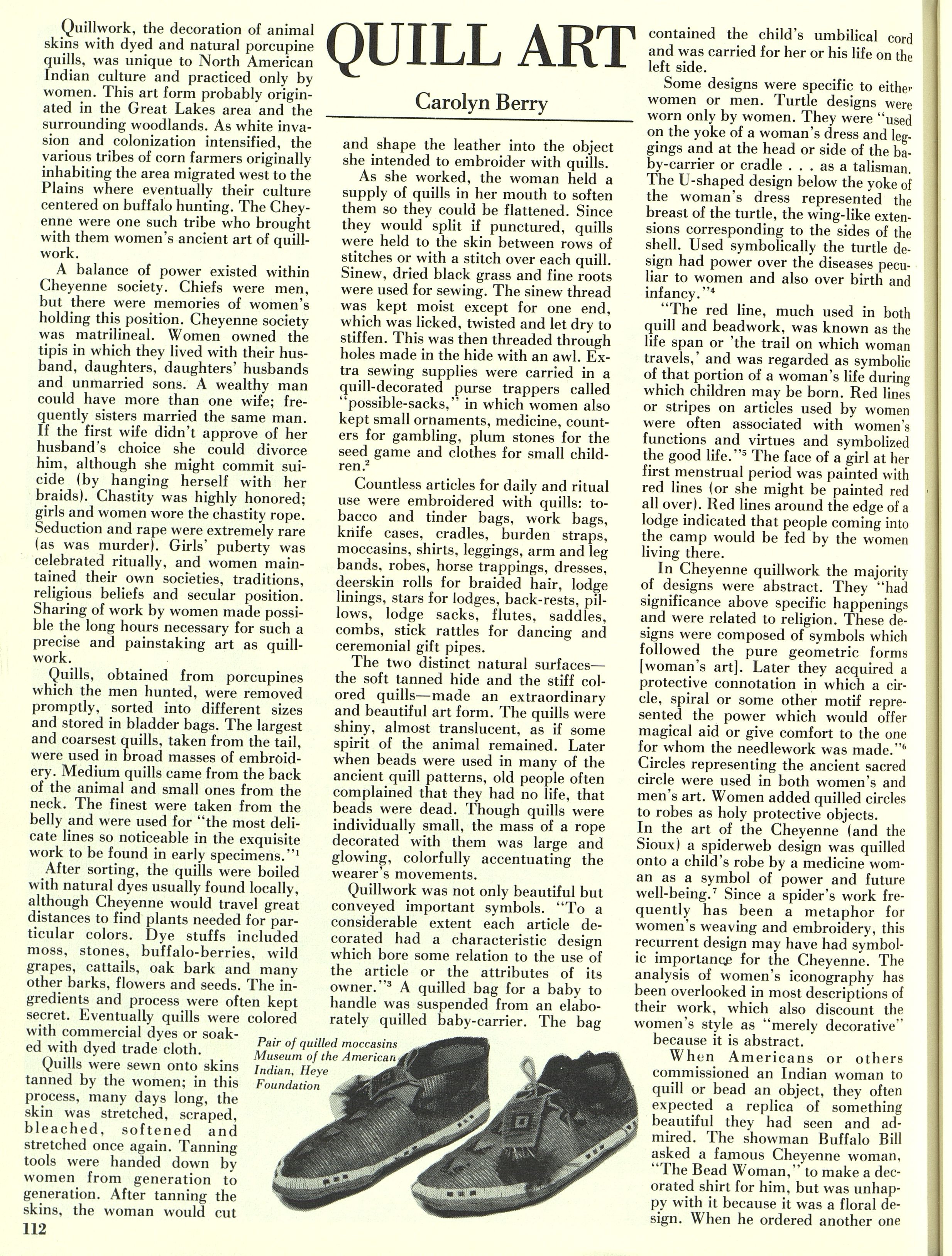

Countless articles for daily and ritual use were embroidered with quills: tobacco and tinder bags, work bags, knife cases, cradles, burden straps, moccasins, shirts, leggings, arm and leg bands, robes, horse trappings, dresses, deerskin rolls for braided hair, lodge linings, stars for lodges, back-rests, pillows, lodge sacks, flutes, saddles combs, stick rattles for dancing and ceremonial gift pipes.

The two distinct natural surfaces—the soft tanned hide and the stiff colored quills—made an extraordinary and beautiful art form. The quills were shiny, almost translucent, as if some spirit of the animal remained. Later when beads were used in many of the ancient quill patterns, old people often complained that they had no life, that beads were dead. Though quills were individually small, the mass of a rope decorated with them was large and glowing, colorfully accentuating the wearer's movements.

Quillwork was not only beautiful but conveyed important symbols. "To a considerable extent each article decorated had a characteristic design which bore some relation to the use of the article or the attributes of its owner." A quilled bag for a baby to handle was suspended from an elaborately quilled baby-carrier. The bag contained the child's umbilical cord and was carried for her or his life on the left side.

Some designs were specific to either women or men. Turtle designs were worn only by women. They were "used on the yoke of a woman's dress and leggings and at the head or side of the baby-carrier or cradle...as a talisman. The U-shaped design below the yoke of the woman's dress represented the breast of the turtle, the wing-like extensions corresponding to the sides of the shell. Used symbolically the turtle design had power over the diseases peculiar to women and also over birth and infancy."

"The red line, much used in both quill and beadwork, was known as the life span or the trail on which woman travels, and was regarded as symbolic of that portion of a woman's life during which children may be born. Red lines or stripes on articles used by women were often associated with women's functions and virtues and symbolized the good life." The face of a girl at her first menstrual period was painted with red lines (or she might be painted red all over). Red lines around the edge of a lodge indicated that people coming into the camp would be fed by the women living there.

In Cheyenne quillwork the majority of designs were abstract. They "had significance above specific happenings and were related to religion. These designs were composed of symbols which followed the pure geometric forms [woman's art]. Later they acquired a protective connotation in which a circle, spiral or some other motif represented the power which would offer magical aid or give comfort to the one for whom the needlework was made." Circles" representing the ancient sacred circle were used in both women's and men's art. Women added quilled circles to robes as holy protective objects.

In the art of the Cheyenne (and the Sioux) a spiderweb design was quilled onto a child's robe by a medicine woman as a symbol of power and future well-being. Since a spider's work frequently has been a metaphor for women's weaving and embroidery, this recurrent design may have had symbolic importance for the Cheyenne. The analysis of women's iconography has been overlooked in most descriptions of their work, which also discount the women's style as merely decorative because it is abstract.

When Americans or others commissioned an Indian woman to quill or bead an object, they often expected a replica of something beautiful they had seen and admired. The showman Buffalo Bill asked a famous Cheyenne woman, "The Bead Woman," to make a decorated shirt for him, but was unhappy with it because it was a floral design. When he ordered another one from another Cheyenne woman he was again disappointed. He was not aware that "the Cheyenne designs are a sacred trust that comes down the woman's line, to be used only for full-bloods."

As quillworkers, women participated in creating ritually important objects. They worked with the men in the creation of scalp shirts which held the hair of enemies killed and horses wounded in battle. Only the bravest men could possess them, and only the most moral women decorated them. Men hunted the animal and women tanned the skin. Men painted the shirt and women quilled or beaded the panels with sacred designs. Each did the work under strict supervision of an honored person of their sex who had done the work before and was ritually approved.

Sacred quillwork was permitted only to members of the Quillworkers Society which, like the Women's War Society, consisted of the most courageous and skilled women, known as Mon in i heo, the selected ones. Quillwork "must be done in prescribed ceremonial fashion, and the [initiate] must be taught to perform it by some member [of the Society] who had previously done the same thing. The making and offering of such a robe [or other item] in the prescribed way secured the maker admission to the Society of women who had done similar things." A candidate would announce her intention to embellish a certain item, usually to bring protection to a child or warrior or to fulfill a sacred vow. If the Society approved, a crier announced the plan to the tribe.

The woman prepared a feast for members of the Society. These individuals reviewed past creations—the designs and the circumstances—very much as warriors recounted their coups. After the feast an old woman was asked to make the design for the robe, which she drew on the skin with a stick and white clay. Throughout the long period of work to make the robe or other objects there were many strict observances. If the woman made a mistake in sewing, a brave man who had counted many coups was called upon. Reciting his experiences, he slipped his knife under the sinew to cut the thread. The completion of the object was announced by the crier of the Society and ceremonies followed.

Cheyenne tradition respected the Quillworkers Society whose "origins were sacred, for their ritual and ceremonies came from the Man who married the Buffalo Wife. The traditions concerning the Buffalo Wife are, in turn, linked to the coming of the Sun Dance ceremonies from the Buffalo people themselves. Part of the strength and power that enabled the women to do the work emanated from the sacred bundle associated with the Society. Their work was so important that a warrior could count coups on a completed work under certain conditions.

Glass beads and woolen and cotton cloth became valued trade items for the Plains tribes. As early as 1595 Europeans were considering what color beads provided the best rate of exchange. Women adopted beads for traditional and innovated designs. By 1850 cloth was replacing skins for use as robes or being combined with skin on various articles. Quilling was the preferred way to embellish highly religious objects, even after beadwork had become popular.

Around the time the tribe was being relocated in Oklahoma (Indian Territory), many fine old pieces were traded for horses, especially when one group, the Northern Cheyenne, started returning to its native lands. Traders, aware of how extraordinary these objects were, had begun to obtain them in the mid-19th century and maybe earlier. It is remarkable that any of the fragile quillwork survived the years of warfare and relocations during which the Cheyenne struggled for their very existence as a culture. Because of the reverence in which sacred quillwork was held, skins decorated with ceremonial symbols were handed down for centuries from one generation to another.

Today Cheyenne women make beadwork in the old way, but it is slow, as it has always been. No one doubts its value or beauty, but the women say no one will pay for the labor necessary to make elaborate pieces with customary care. Despite the difficulty for Cheyenne women of obtaining materials and the necessity of their selling work for income, the Beadworkers Society still sponsors women's honored work, continuing traditional tribal values. Its existence reflects the strength of Cheyenne women—particularly as a force for maintaining their culture in the rapidly-changing world in which they now live.

Carolyn Berry is an artist and writer. She directs a sheltered workshop for handicapped adults in Monterey, California.