View the Issue

Read the Texts

Mexican Folk Pottery

Editorial Statement

The Aesthetics of Oppression

Is There a Feminine Aesthetic?

Quilt Poem

Women Talking, Women Thinking

The Martyr Arts

The Straits of Literature and History

Afro-Carolinian "Gullah" Baskets

The Left Hand of History

Weaving

Political Fabrications: Women's Textiles in Five Cultures

Art Hysterical Notions of Progress and Culture

Excerpts from Women and the Decorative Arts

The Woman's Building

Ten Ways to Look at a Flower

Trapped Women: Two Sister Designers, Margaret and Frances MacDonald

Adelaide Alsop Robineau: Ceramist from Syracuse

Women of the Bauhaus

Portrait of Frida Kahlo as a Tehuana

Feminism: Has It Changed Art History?

Are You a Closet Collector?

Making Something From Nothing

Waste Not/Want Not: Femmage

Sewing With My Great-Aunt Leonie Amestoy

The Apron: Status Symbol or Stitchery Sample?

Conversations and Reminiscences

Grandma Sara Bakes

Aran Kitchens, Aran Sweaters

Nepal Hill Art and Women's Traditions

The Equivocal Role of Women Artists in Non-Literate Cultures

Women's Art in Village India

Pages from an Asian Notebook

Quill Art

Turkmen Women, Weaving and Cultural Change

Kongo Pottery

Myth and the Sexual Division of Labor

Recitation of the Yoruba Bride

"By the Lakeside There Is an Echo": Towards a History of Women's Traditional Arts

Bibliography

The Aesthetics of Oppression: Traditional Arts of Women in Mexico

Judith Friedlander

What do we mean by the traditional arts of women? All too often we are talking about activities that are not considered art either by the women who perform the tasks or by the societies in which they live. Some peoples do not conceptualize transforming mere cultural When I talk about culture and cultural activities, I am using the terms in the anthropological sense. I am not referring to CULTURE as it has been developed in Western society. Following T. Parsons, C. Geertz, and D. Schneider, by culture I mean a system of symbols shared by a group of people (D. Schneider, 1968, p. 1). activities into the domain of art. When the category does exist, women rarely emerge as the great artists. Coming from a society where art is recognized, valued and produced almost entirely by men, it is not surprising that American feminists are interested in looking at the relationship women have to art in other cultures, to see if the comparison sheds additional light on the American condition. Before entering into such a discussion with material from Mexico, however, we should provide a more specific context for the cross-cultural analysis by reviewing some issues concerning art in the United States.

Our society has a hierarchical view of art, making rigorous distinctions Page: 4between the so-called fine arts and the traditional or folk. The nature of fine arts is individualistic, that of the folk, collective. The fine arts represent the work of specialists, recognized personalities who dedicate themselves almost exclusively to their art. Even when they supplement their incomes with additional jobs, the culture sees them as artists first. The folk arts, on the contrary, are the work of nonspecialists, unknown people who are, perhaps, farmers, fishermen, miners, individuals who make modest livings in "old-fashioned" ways and happen to produce folk art on the side. What is more, according to cultural definitions, folk artists do not create so much as carry on timeless traditions. They are living vestiges of the past and the more obscure they are, the more authentic they appear.

In a culture where progress, specialization, and rugged individualism are valued, why have we created and maintained such a static category as the traditional arts? We could argue that the anonymity and timelessness imposed on folk art permit those who practice the fine arts to borrow freely from traditional motifs. Who would accuse a Bartók of plagiarism just because he used Hungarian peasant melodies? Less cynically, but troubling all the same, we might suggest that the alienation of our lives in modern America has awakened in many a yearning for simpler times and forms. Yet in order to have the "folk," a group of people must preserve for us the ways of the past—in the hills of Appalachia, in the African bush, or in mud huts in Mexico.

Feminists today are well acquainted with the cultural strategy that keeps folk artists in the obscurity of their grass-roots authenticity, for women have been erased in similar ways. Like the folk artist, woman is by definition a nonspecialist and a carrier of traditions. She is first and foremost a wife-mother whose social and economic duties prevent her from having the time to specialize. Then, even if class privilege gives her the option to refuse her sex's destiny, she still has to fight the culture's traditional view that her creative powers are limited by her biology.

Our culture has so successfully confined the arts to the male sphere that it has developed sex-specific vocabularies to distinguish work done by men (specialized) from that done by women (generalized). Thus, although tasks traditionally assigned to women usually fall outside the arts entirely, a number of skills become lesser arts when performed by male specialists. Women, for example, do sewing and cooking. Men are couturiérs or chefs. Careful to mark the status relationships, we borrow terms from the lofty French to describe the specialized work of a man, leaving the lower-class Anglo-Saxon to identify the chores that fragment a woman's day. Of course, there are female couturiéres and chefs, and the numbers are undoubtedly growing as women today succeed in becoming professionals in these and other fields. Yet recent changes do not negate the long cultural history of the sexes in American society in which men (at least of certain classes) have been encouraged to specialize, while women (despite their class) have almost always been less rigorously trained, at best educated to dabble in a few areas, but by and large inadequately prepared for anything other than, perhaps, wifing and mothering.

While feminist artists continue their struggle to change cultural definitions and thereby gain entry into the male-dominated world of the fine arts, some are also trying to open the Academy to work usually associated with the "inferior" crafts or simply with the domain of women’s work. In the process, they have been collecting the nearly forgotten traditions of women in rural America and abroad, creating a specifically female folk culture by bringing to light previously unrecognized skills of unknown women who never had the chance to specialize. Given feminist consciousness, we can hope that those who produce the recently recognized art will emerge from obscurity as individuals, instead of being reduced to the collective anonymity so characteristically the fate of traditional artists. Still, lingering questions must be raised, for it is not entirely clear that we see what our interest in folk art may mean for those women who happen to be carrying on our timeless, authentic female culture.

Other political movements have heralded the art of the folk while fighting to end their oppression—i.e., the Narodniks in czarist Russia, intellectuals in the Mexican Revolution and Irish revolutions, leaders of Black power movements and Native American Power movements—and it might be useful to analyze their histories carefully. As a start, let us look at post-revolutionary Mexico, where we shall see how the enthusiasm expressed by urban political leaders for traditional culture has been a mixed blessing, particularly for those who have been living the impoverished reality which seems to preserve folk art the best. Specifically, we shall see how Indian women from Hueyapan, a highland village in the state of Morelos, have been encouraged to maintain their so-called Indian culture—in essence, their lower socioeconomic status—by a nation whose "revolutionary" ideals call for the preservation of Mexico's indigenous heritage.

A Mexican Indian Example

Looking at the traditional culture of Hueyapan is like looking into a reservoir of oppression. It is a mixture of cultural hand-me-downs from the ruling class, combined with a few vestiges from pre-Hispanic times that have managed to survive over 400 years of Spanish/Hispanic occupation. We find, for example, under the rubric of indigenous culture, sixteenth-century Spanish colonial dress, medieval miracle plays, and Renaissance double-reeded instruments played only to celebrate Catholic fiesta days. As for those customs which are truly of pre-Hispanic origin, they have been transformed almost beyond recognition to conform to the dictates of Hispanic cultural rules. What is more, these modified indigenous forms frequently exist only because they have become part of the dominant culture as well.

After the Revolution of 1910-1920, the Mexican government began actively to preserve and reinforce so-called indigenous customs. For ideological purposes, political leaders wanted to glorify the country's unique heritage, partly Spanish, partly Indian. Artists painted, choreographed, and wrote about Indians, while philosophers philosophized about them. Archeologists, sculptors, and architects labored to restore and celebrate pre-Hispanic culture. Folk arts began to flourish. So successful was this cultural renaissance that by the 1950s tourists were flocking to Mexico to visit museums and pre-Hispanic ruins, to purchase inexpensive traditional art objects and to travel into the interior to see how the Indians lived in their natural habitats.

In the eyes of many Hueyapeños, this glorificaiton of Mexico's "roots" can do little more than reinforce their oppression. Living in a community where the socioeconomic realities of their traditional culture prohibit them from enjoying the conveniences of modern Mexico, they claim that the only viable future for the villagers lies in losing their Indian identity. Many of the young people, particularly women, are not waiting for changes to take place in Heuyapan and have migrated instead to Mexico City and Cuernavaca. Page: 5As far as they are concerned, it is better to work long hours as maids in comfortable homes, or live in the urban slums, than to remain in Hueyapan and continue their tedious – albeit "folkloric" – Indian existence.

That more women than men want to leave Hueyapan is directly related to the distribution of so-called traditional culture in the village. In a society where being traditional or indigenous still brings both low social status and hard work, the world of Hueyapan women is decidedly more Indian than that of its men. What is true here simply supports what anthropologists writing about modernization have found elsewhere: almost always men assimilate more quickly in Third World countries, for capitalist and socialist systems integrate them more rapidly into urban and rural work forces. Women who do not become maids in the cities are often isolated at home where they provide unpaid labor by taking care of their husbands and reproducing new workers, remaining, as a result, more "conservative" culturally. Even in places where men no longer practice traditional customs, women often continue to do so, speaking the local language among themselves, dressing in the old way and continuing to work with little help from labor-saving technology. This argument has been particularly well developed by Ester Boserup, 1970 As any Hueyapan woman will explain, women who stay in the village are the last to change.

The Mexican government has further contributed to the division between the modernizing man and the traditional woman by its interest in promoting indigenous culture. On the one hand, it has provided more training and technology to change the nature of men's work than women's. On the other hand, it has encouraged women more than men to develop their traditional skills. In Hueyapan, for instance, where weaving still exists, government programs have tried to interest local women in making shawls, ponchos and scarves for the tourist trade. What is more, when government representatives come to the village on official visits—an event that happens several times a year—they appreciate it if the Hueyapeños welcome them with an ethnic reception. Thus, in the name of paying homage to Mexico’s Indigenous heritage, young girls are dressed up in the so-called Indian costume The clothing traditionally worn by the women conforms to the dictates of Carlos V, who during the early part of the colonial period sent formal orders to Mexico that Indians had to dress according to Spanish styles and an Iberian sense of decency. (Foster, 1960, pp. 101-102). native to the area and receive the honored guests with flowers and little speeches in Nahuatl. Nahuatl was the language of the Aztecs and is still spoken in Hueyapan—in a form strongly influenced by the Spanish—by the old, particularly the women. To this day, the villagers believe what they were told in colonial times, that Nahuatl is not a language, but only a dialect, which has no grammar or literature. Furthermore, women prepare a mole mealMole is most commonly used as a sauce or dressing for meats. It can be made in a variety of different ways, but often times has nuts or seeds, chili peppers, and fresh spices. They can also have fresh or dried fruits as well. , the traditional fiesta dish, for these government representatives.

To move to a more specific analysis, we could look at almost any one of the so-called indigenous traditions found in Hueyapan today to illustrate in concrete terms how the villagers' culture reflects their long history of being dominated by a non-Indian society. Although industrialization has hardly brought liberation, it is still a fact that the poorest rural communities throughout Mexico are generally the most "Indian." What is more, as these villages begin to change, traditional culture holds on the longest among the most oppressed inhabitants, particularly the women, who for social, economic and cultural reasons remain more isolated from the influences of modernization. Given that Mexico is interested in both industrializing the country and preserving its so-called indigenous heritage, we could suggest that one resolution of the problem has been to "develop" one sex and sustain the past with the other. Drawing on traditional Hispanic definitions of sex roles and status differentiations between men and women, the choice was easily made. For purposes of this discussion, then, let us turn to traditional cooking to see what the preservation of this "folk art" has meant in the daily lives of Hueyapan women.

The Art of Cooking

In a recent article entitled "The Magic of Mexican Food North of the Border,” Craig Claiborne whimsically begins:

For some confounding reason known only to a few Aztec gods, the authentic flavors of the Mexican kitchen, like certain fine wines and some exotic plants, do not travel well. They transport poorly through some curious dilution of tastes, some diminution of savor, some evanescence of essences [New York Times, September 21, 1977].

Could Claiborne have written this if he had tasted Mexican food prepared in an indigenous peasant village? His calling forth of mystery, humor, and romance inadequately describes what one experiences in today's closest equivalent to an Aztec kitchen. There, it is true, the ingredients are very fresh and the food has that special aroma of the open hearth, but it also has been ground first, for tedious hours, on special volcanic stones (metates) that are generations old, and cooked in earthenware pots seasoned by years of use. There is no secret why Mexican food does not travel; it cannot even be recreated properly in Mexico City, much less New York. What we lack are the necessary "rustic" working conditions and equipment.

While members of the privileged classes, particularly from abroad, have come to appreciate Mexican cooking as one of the world's great cuisines, for Hueyapeños it remains one of the endless chores that women must attend to in the course of a day's work. As far as many villagers are concerned, the food they eat and the process involved in its preparation are merely additional indications of their inferior status. If they had the means, therefore, they would stop eating like Indians and would eat as they think the rich do, buying food in tin cans and cellophane packages which they—or preferably a maid—would heat quickly over a gas stove. Although most Hueyapeños recognize that certain foods, tortillas for example, taste better when prepared at home, the labor entailed is enormous, encouraging the women, more than the men, to seek ways of simplifying the work.

In almost every home in Hueyapan, the basic daily diet consists of tortillas and boiled beans served with chile peppers, sometimes in a sauce, sometimes just off the vine. Descriptions of the ingredients and preparation of most of the dishes mentioned can be found in the recipe section at the end of this article. My information comes from experiences cooking with women in Hueyapan during fiestas in 1969-70 and on subsequent visits in 1971, 1973, 1974, 1975, 1976 as well as daily exposure during the same time in the home of Doña Zeferina Barreto, where she and her daughter-in-law cooked for 14 people. At every meal, even among the poorest, one is sure to have these staple foods and then, depending on the family’s income, the productivity of the barnyard, fields and orchards, other dishes may be added. At breakfast and supper—the latter being a very light meal with perhaps only one tortilla wrapped around a few beans— weak and highly sweetened coffee or herbal tea is served, substituted on rare occasions by hot chocolate. Coffee, like chocolate, is expensive and must be purchased, while most of the teas are grown locally. Sweet rolls (pan dulce) baked in the village and bought at nearby stores are also frequently served at breakfast or dinner, particularly to children.

If the family can afford it, women usually prepare additional dishes for the main meal at midday. Lunch specialties may be nothing more elaborate than one of several kinds of chile sauces, beans prepared with the flavorful ayocote flower or fried in a bit of lard. But on market day, a piece of beef or pork may also be added (one kilo for about 14 people), boiled with seasonings and served in its broth. Beef may be cooked in a beef mole soup instead. When meat is unavailable or too expensive, noodle soup, prepared with pork fat, or pork rind fried in a soupy, green chile sauce provide substitutes. Although chickens and turkeys are fiesta foods only, eggs fried in pork fat and a chile sauce may also appear, perhaps once a week, in the diet of families Page: 6 who raise laying hens or have enough money to purchase eggs at the store (four or five eggs would serve 14 people). Another popular dish, when they are in season, is stewed prickly pear cactus shoots (nopalitos). Finally, after fiestas, the leftover mole sauce (see below) is used to make enchiladas and chilaquiles.

Women prepare the most elaborate meals on fiesta days. Traditionally Hueyapeños celebrate at least ten village-wide Catholic fiestas as well as the individual saint days of members of the family. Since the Mexican Revolution, about five national holidays have been added. All celebrations, be they religious or secular, village-wide or family, are feted by serving a traditional menu. Although Hueyapeños share responsibilities by sponsoring one fiesta or another in a given year, at which time they have an open house, most families who can manage to—and most sacrifice so that they can—still celebrate at home as well, at least for the most important fiestas. Relatives, compadres, and comadres (individuals with whom the family has a formal ritual relationship blessed by the Church), and political friends, visit one another at these times, eating the same traditional dishes at each home.

For birthdays and other family-based holidays, there is a special breakfast of atole and meat tamales as well as the elaborate midday meal. Meat tamales take hours to prepare and must be made the night before by a team of women—usually the mother-in-law, the wife, perhaps a teenage daughter still living at home, and a compadre or two (in particular widows with no family left in the village who have time to help on such occasions). Since the work goes on late into the night, only to begin again before dawn the next day, the invited assistants do not bother to go home, but wrap themselves up in blankets they bring along with them and curl up on straw mats placed on the dirt floor in the kitchen. Thus, by the time the male family members and a few guests—mostly men as well—are enjoying a tamale-atole breakfast, the women have long been at work, some looking after the hot atole corn meal drink and others attending to the main meal of the day, butchering turkeys or chickens, cooking the soup, the rice, the mole colorado, For less formal affairs, the preferred mole colorado may be substi- tuted by one of the less complicated green moles, like the pum- pkin seed mole listed in the recipe section. the bean and plain tamales, the boiled beans, and the countless tortillas.

Fiestas, it is true, give women the chance to cook, eat, and drink together, certainly providing some relief from their normal routines. Still, the work is exhausting and may go on for several days, rarely letting up enough for women to have a chance to leave the kitchen and enjoy the dancing or other party activities. What is more, once the holiday is over, women, particularly mothers with young children, are faced once again with their strenuous daily schedules.

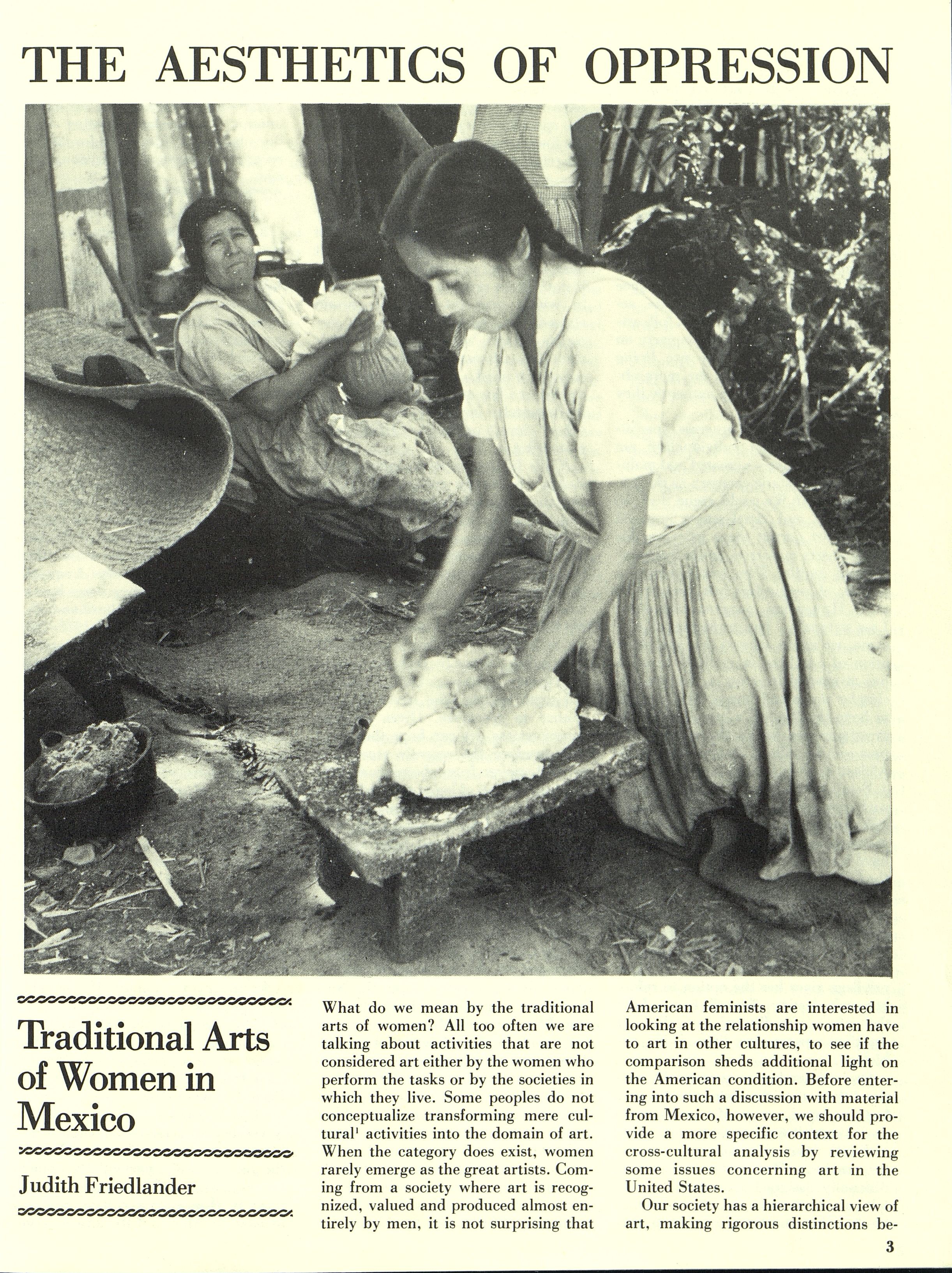

Mexican cooking is difficult and time-consuming under traditional conditions mainly because almost every ingredient must be ground finely by hand—from the corn used in tortillas tamales and atole, to every spice and vegetable added to a mole or chile sauce. The work is back-breaking, even for women used to it, and must be performed kneeling before the large grinding stone (metate), a kitchen utensil known pre-Hispanically throughout America.

Since the 1950s Hueyapan has actually had a number of corn mills, eliminating the need to grind corn by hand. According to the women, however, many men initially objected to the mills. Not only did they complain about the cost (two cents a bucket), but they did not like the texture of millground tortillas. Corn ground on the metates simply tasted better. Another innovation which met with a mixed reaction was the tortilla press, used to shape tortillas that traditionally are fashioned between a woman’s hands into paper-thin disks.

Despite the new improvements, the work of "throwing" tortillas remains endless, for a family of 14 eats well over 50 at one meal and expects them fresh and hot off the griddle at least twice a day. What women really need to simplify their work is a tortilla factory, where hot tortillas can be purchased before each meal. While many non-Indian communities surrounding the village have such tortillerías, there is no talk as yet of introducing one into Hueyapan.

Given the argument developed so far we can now conclude with a few recipes, letting the descriptions of the preparations and the ingredients speak for themselves. No attempt will be made here to help the reader reproduce these dishes in a modern kitchen, nor will proportions be systematically provided. Traditional Mexican cooking, at least in Hueyapan, has been a matter of availability of resources: what has been harvested, what the family can afford to buy, how many people must be fed with a small fixed budget. One chicken, for example, can easily serve 20 people. When the soup gets low, one just adds more water and another leaf of peppermint. There are no exact amounts of this's and that's and it would therefore be an arbitrary exercise to suggest that there were.

What can be discussed is the labor involved in preparing a particular dish and whether the ingredients are grown locally or must be purchased. Furthermore, we can note the origins of the ingredients at the time of conquest to aid us in identifying the influences Hispanic tastes have had on so-called indigenous food.

It will become immediately evident that fiesta food, more than the basic staples, shows considerable Iberian/Old World influence. This is hardly surprising when we remember that all aspects of the Indians' ritual life became the solemn responsibility of the Catholic missionaries who settled in indigenous towns during the early colonial period, converting the people and transforming their culture. Hueyapan was conquered in 1524, only three years after the Aztec Empire fell. By the 1530s Augustinian missionaries had come to the area and by 1561 the Dominicans had already built a church, monastery, and several chapels in the pueblo (Martinez-Marin, 1968, p. 64ff). Page: 7

RECIPES

Tortillas

| Ingredient | Availability to Villagers | Origin of Ingredient At Time of Conquest |

| Corn | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Lime (CaCo2) | Must be purchased | Indigenous |

| Salt | Must be purchased | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

After the corn has been harvested and dried, women remove the kernels from the cob and store them in enormous sacks, weighing about 100 pounds each. Daily about ten liters measures of dry corn (for a family of 14) have to be boiled with a fistful of lime and a bit of salt. Originally the corn was boiled in large earthenware jars (ollas) but today it is more frequently boiled in tin cans. It takes several hours for the corn to soften to the right texture.

The corn cools, and then a standard-size bucket of kernels is ground for the breakfast tortillas. Before "throwing" tortillas, however, the corn meal must be kneaded to the proper consistency. Often water is added. Little round balls of the moist meal (masa) are shaped into thin round tortillas and toasted over the hearth on a clay disc that has been washed down with lime. Successful tortillas are thin and inflate just a bit while cooking. They should be served hot off the fire and are preferably prepared throughout the meal by a female member of the family who eats later. The tortilla is not only a food but is also used as an eating utensil, a scoop for beans and other food.

Boiled Beans (Frijoles de Olla)

| Kidney beans or | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Avocote (large brown beans) | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Onion | Grown locally | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

| Salt | Must be purchased | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

| Epazote | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Garlic | Must be purchased | European |

The dried kidney or ayocote beans are boiled with the above ingredients for several hours until tender. The garlic clove is left whole and the onion is sliced. Epazote leaves are added to season the water further as are, occasionally, the flowers of the ayocote.

The beans are boiled in an olla.

Fried Beans

| Lard | Usually purchased | European |

Other ingredients the same as for boiled beans.

A small portion of the boiled beans are fried in pork fat Pigs, like steer, are slaughtered in the village by the Hueyapan butcher. With the exception of chickens and turkeys, few families butcher their own animals, but sell them alive and purchase back a small quantity of meat. in an earthenware casserole and then mixed together with the beans in the olla.

It should be noted that although the wealthier Aztecs ate wild boar (peccary) (Soustelle, 1961, p. 151), the pork eaten in the village seems to come out of Spanish culinary practices.

Green Chile Sauce

| Green chile (ancho) | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Green tomato or | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Red tomato | Must be purchased | South American |

| Onion | Grown locally | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

| Fresh coriander | Grown locally | East Indian |

| Salt | Must be purchased | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

| Water |

The chile pepper is briefly roasted over the coals and peeled. The tomato is also peeled after it has been dipped into boiling water. All the ingredients are then ground together either on the metate or in a volcanic stone mortar and pestle.

Beef, Pork, Chicken or Turkey Soup

| Turkey or | Raised locally | Indigenous |

| Chicken or | Raised locally | European |

| Beef or | Usually purchased | European |

| Pork | Usually purchased | European |

| Peppermint | Grown locally | European |

| Onion | Grown locally | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

| Garlic | Must be purchased | European |

Any one of the above meats is boiled with the other ingredients in an olla. The soup is served with a small piece of meat and then the following ingredients are added to taste by the person eating.

| Lime juice | Must be purchased | Mediterranean fruit |

| Green delgado chile (chopped) | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Onion (chopped) | Grown Locally | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

| Salt | Must be purchased | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

Beef Mole Soup

| Beef | Usually purchased | European |

| Peppermint | Grown locally | European |

| Fresh coriander | Grown locally | East Indian |

| Green tomato | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Onion | Grown locally | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

| Salt | Must be purchased | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

| Water | ||

| Green chile (ancho) | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Cloves | Must be purchased | Moluccan |

| Black pepper | Must be purchased | East Indian |

The chile pepper and green onion are peeled and ground together with the cloves and black pepper. All the ingredients are then boiled in an olla. Each person is served a small piece of meat with the broth.

Enchiladas

| Fresh tortillas | See above | See above |

| Mole colorado sauce | See below | See below |

| Fresh cream or white crumbly cheese | Must be purchased | European |

| Lard | Usually purchased | European |

Fresh tortillas are fried in lard and rolled into tubular shapes. Mole colorado sauce is then poured over them and the mixture is heated in an earthenware casserole. If it is available, the enchiladas can be served with fresh cream or white crumbly cheese. Mexican restaurants serve enchiladas with chicken or some other meat, but this is not the case in homes in Hueyapan.

Chilaquiles

The same as above only made with stale tortillas that have been torn into pieces.

Tacos

Tacos are fresh tortillas filled with meat, rice, or hard-boiled eggs. They are always served with chiles.

Nopalitos

| Prickly pear shoots | Grown locally | Indigenous w/Mediterranean equiv. |

| Onion | Grown locally | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

| Red tomatoes | Must be purchased | South American |

| Chile ancho | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Lard | Usually purchased | European |

| Salt | Must be purchased | Indigenous w/ European equiv. |

The prickly pear shoots are scraped clean of their spines and cut into small cubes. The onion, peeled tomatoes, and chiles are ground together and seasoned with salt. All ingredients are fried in lard in an earthenware casserole.

Fiesta Food

Atole

| Corn meal | See above | See above |

| Powdered milk (optional) | Must be purchased | European |

| Cane sugar | Must be purchased | Middle Eastern and Oriental |

| Chocolate or | Must be purchased | Indigenous |

| Cinnamon or | Must be purchased | Sinhalese and Chinese |

| Green corn kernels | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Water |

Corn meal is stirred into heating water and milk, making a thick but drinkable porridge. This mixture is flavored with ground chocolate, cinnamon or the whole kernels of corn and then heavily sweetened. It is cooked in an olla and served hot. It should be noted that although chocolate is indigenous to Mexico, it comes from the tropical lowlands and was probably not used by the highland Morelos Indians pre-Hispanically.

Meat Tamales

| Corn meal | See above | See above |

| Pork | Usually purchased | European |

| Lard | Usually purchased | European |

| Guajillo chile | Must be purchased | Indigenous |

| Corn husks | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Totomoscle leaves | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Water |

The pork is cubed and fried with the red guajillo chile which has been softened in boiling water and ground on the metate. Before making the tamales, the corn meal is kneaded to the proper consistency. Then, taking a bit of corn meal the size of a meatball and stuffing it with the meat and chile mixture, the tamale is wrapped carefully in a corn husk, assuming the shape of a small corn cob. Finally, it is placed in a huge olla where perhaps 200 similar tamales are huddled together and steamed for a couple of hours. The olla must be sealed closed with totomoscle bush leaves—huge, flat, and highly absorbent.

Bean Tamales

| Corn meal | See above | See above |

| Ayocote beans | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Salt | Must be purchased | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

| Water | ||

| Corn husks | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Totomoscle leaves | Grown locally | Indigenous |

The corn meal is kneaded to the proper consistency. Salt and water are added. The boiled ayocote beans (see above) must be ground on the metate. Some of the corn meal is then spread over the surface of the metate which in turn is covered by a layer of ground beans and another layer of corn meal. The "marble" corn is fashioned into tamales, again in the shape of small corn cobs, wrapped in corn husks, and steamed in a huge olla that has been covered with totomoscle leaves.

A plain tamale, made only of corn meal, is prepared in the same way. It is flat, however, not round, and serves as a scoop for food much like a tortilla.

Rice (Sopa de Arroz)

| Rice | Must be purchased | Old World |

| Red tomatoes | Must be purchased | South American |

| Green peas | Grown locally | European |

| Onions | Grown locally | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

| Lard | Usually purchased | European |

| Salt | Must be purchased | Indigenous w/European equiv. |

| Water |

The raw rice is sautéed with peeled tomatoes which have been ground with onions and seasoned with salt. Water and green peas are then added and the mixture simmers until done. The rice is cooked in an earthenware casserole and is usually served as the first course of a fiesta dinner.

Squash-Seed Mole

| Ancho chiles | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Green tomatoes | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Chicken or pork soup | See above | See above |

| Squash seeds | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Epazote | Grown locally | Indigenous |

| Lard | Usually purchased | European |

| Salt | Must be purchased | Indigenous w/ European equiv. |

The chiles and green tomatoes are peeled and ground on the metate. The squash seeds are very finely ground. These three ingredients, seasoned with salt, are fried in lard. Soup and epazote leaves are added and the mixture simmers for about an hour.

The sauce is served over chicken or pork. Although it should be reasonably thick and have a nutty taste, the sauce should also have a fine texture. Tamales (bean and plain) are served with the mole as are tortillas. Boiled beans (see above) follow as the last course.

Mole Colorado (Mole Poblano)

| Pasilla chile | Must be purchased | Indigenous |

| Sesame seeds | Must be purchased | E. Indian |

| Chocolate (bitter) | Must be purchased | Indigenous |

| Peanuts | Must be purchased | Indigenous |

| Cloves | Must be purchased | Moluccan |

| Cumin | Must be purchased | Hindustani |

| Black pepper | Must be purchased | E. Indian |

| Cinnamon | Must be purchased | Sinhalese and Chinese |

| Almonds | Must be purchased | Moroccan |

| Anise | Must be purchased | N. African |

| Raisins | Must be purchased | European |

| Garlic | Must be purchased | European |

| Onions | Grown locally | Indigenous w/ European equiv. |

| Salt bread (stale) | Must be purchased | European |

| Tortilla (stale) | See above | See above |

| Chicken or Turkey soup | See above | See above |

| Lard | Usually purchased | European |

To make enough mole to serve with one hen (to feed about 20 people), Hueyapan women usually use ¼ kilo of pasilla chile, ¼ kilo sesame seeds, and as much as they care to or can afford of the other ingredients—usually small quantities.

All the spices, including the onions, bread, and tortillas have to be ground very finely. The pasilla chile (a dark red, flat pepper) is purchased dry and soaked first in boiling water. The ground ingredients are then sautéed in lard and finally, the soup is added. The mixture simmers for about an hour and is then served over chicken or turkey. Bean and plain tamales as well as fresh tortillas are served along with it. Boiled beans follow as the last course.

Mole colorado is the most important fiesta food in the village. Keeping in mind what we have already said about the way Spanish priests probably influenced fiesta cooking, it is particularly interesting to see what happened to the pre-Hispanic mole.

According to Soustelle, in The Daily Life of the Aztecs, this dish originally was nothing more than a chile stew (Soustelle, 1962, p. 27). After the conquest, however, mole came to resemble an East Indian curry. Thus not only did Spaniards call the inhabitants of Mexico Indian, but they also altered one of the most common Aztec recipes to support this error of ethnic identity.

A standard curry has the following ingredients: coriander, cumin, turmeric, nutmeg, cloves, red pepper, onions, raisins, almonds, walnuts, cashew nuts, coconut, white poppy seeds and yogurt.

References

- Boserup, E., Woman’s Role in Economic Development. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1970.

- Claiborne, C., “The Magic of Mexican Food North of the Border." The New York Times, September 21, 1977, pp. CI, C8.

- Foster, G., Culture and Conquest: America’s Spanish Heritage. New York: Viking Fund Publication in Anthropology, No. 27. 1960.

- Friedlander, J., Being Indian in Hueyapan: A Study of Forced Identity in Contemporary Mexico. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1975.

- Martinez-Marin, C., Tetela del Volcan. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico Press, 1968.

- Schneider, D., American Kinship. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1968.

- Soustelle, J., The Daily Life of the Aztecs, trans. P. O’Brien. New York: Macmillan, 1962.

Judith Friedlander is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology teaching at the State University of New York at Purchase. She was one of the organizers of the N.Y. Tribunal on Crimes against Women, 1976, and is a member of the Marxist-Feminist Group III.