Mexican Folk Pottery

Editorial Statement

The Aesthetics of Oppression

Is There a Feminine Aesthetic?

Quilt Poem

Women Talking, Women Thinking

The Martyr Arts

The Straits of Literature and History

Afro-Carolinian "Gullah" Baskets

The Left Hand of History

Weaving

Political Fabrications: Women's Textiles in Five Cultures

Art Hysterical Notions of Progress and Culture

Excerpts from Women and the Decorative Arts

The Woman's Building

Ten Ways to Look at a Flower

Trapped Women: Two Sister Designers, Margaret and Frances MacDonald

Adelaide Alsop Robineau: Ceramist from Syracuse

Women of the Bauhaus

Portrait of Frida Kahlo as a Tehuana

Feminism: Has It Changed Art History?

Are You a Closet Collector?

Making Something From Nothing

Waste Not/Want Not: Femmage

Sewing With My Great-Aunt Leonie Amestoy

The Apron: Status Symbol or Stitchery Sample?

Conversations and Reminiscences

Grandma Sara Bakes

Aran Kitchens, Aran Sweaters

Nepal Hill Art and Women's Traditions

The Equivocal Role of Women Artists in Non-Literate Cultures

Women's Art in Village India

Pages from an Asian Notebook

Quill Art

Turkmen Women, Weaving and Cultural Change

Kongo Pottery

Myth and the Sexual Division of Labor

Recitation of the Yoruba Bride

"By the Lakeside There Is an Echo": Towards a History of Women's Traditional Arts

Bibliography

Peg Weiss

Adelaide Alsop Robineau (1865-1929) who worked and lived most of her life in Syracuse, New York, was one of the foremost ceramists of her time and is today regarded by many as America's greatest ceramist. She was a perfectionist: in 25 years of continued creativity she produced only 600 works which she deemed worthy of survival. [1According to her husband’s recollection, "All the unsatisfactory pieces were reglazed and refired until they came out good or (were) entirely spoiled." (Samuel E. Robineau, “Adelaide Alsop Robineau, Design XXX, no. 11 [April, 1929], p. 205.)] Nearly every known piece is a superior example of its type, whether it be the grand feu (high-fire) porcelain at which she excelled or stoneware; crystalline glaze or flammé; excised or pierced egg shell.

Born in Middletown, Connecticut, the daughter of an engineer and inventor, Adelaide Alsop was artistically talented and determined to be self-supporting. She first turned to the decoration of porcelain, teaching herself the technique from books. She was soon proficient enough to become a teacher of porcelain painting, a career she pursued for several years at St. Mary's Hall school in Minnesota. In the early 1890s she returned to New York where she studied painting briefly with William Merritt Chase, still supporting herself as a china decorator.

At 34, she married Samuel Robineau whom she had met in the Midwest. They joined G. H. Clark in Syracuse to found and publish Keramic Studio with Adelaide Robineau as editor. The new porcelain painters' magazine soon dominated the field. A typical issue might include descriptions of new materials and techniques, an art historical article on Chinese porcelain painting and Robineau's own designs and writings. Keramic Studio complemented another nationally known magazine published in the Syracuse area, The Craftsman. Edited by Gustave Stickley, creator of "Mission" furniture, it promoted the ideals of the international arts and crafts movement inherited from William Morris. The magazines were extremely influential to the development and flourishing of the American arts and crafts movement, achieving national circulation in a short time.

In 1903, Samuel Robineau translated and published in Keramic Studio a series of articles by Taxile Doat, the Sevres master, on the making of grand feu porcelain. [2The essays by Doat were later published in book form as Grand Feu Ceramics (Syracuse, N.Y.: Keramic Studio Publishing Co., 1905).] Adelaide Robineau had longed to create new forms and inspired by these articles she went to study with Charles Binns at the pottery school in Alfred, New York. She then set up her own kiln at home and fired her first batch of porcelains, with her husband serving as her advisor and technician. She experimented alone, however, with different clay bodies and developed a remarkable range of glazes, fixed and flowing, crystalline and matte, for which she is famous. [3The distinction between Adelaide's creative work in inventing forms, glazes and decorations and in making the actual pieces, and Samuel’s advisory role as firing technician has been underscored by their daughter, Mrs. Elizabeth Lineaweaver, in a recent interview with the author.] She also experimented endlessly to adjust Doat's formulas to her own materials and discovered a special variety of Texas kaolin that lent itself to her requirements of translucency and strength.

In 1903-1904, the Robineaus built a house and separate studio on a hillside overlooking Syracuse which Adelaide designed with an architect friend, Katharine Budd. The studio building consisted of three stories: the kiln area on the first floor, the pottery on the second and a playroom for the three Robineau children on the third. Having the children nearby while mother pursued her profession was considered drastically "modern" when the Robineau home was featured in American Homes and Gardens in 1910. [4Grace Wickham Curran, "An American Potter, her Home and Studio," American Homes and Gardens (Sept., 1910), pp. 364-366.] The buildings still stand on Robineau Road in Syracuse.

Adelaide Robineau's brilliant experiments included the oxblood flammé of Chinese tradition, crystalline glazes in blue, white and maize, crackles and inlaid slip designs. She undertook a challenge most of her contemporaries thought was impossible: the creation of eggshell "coupes" or shallow rimless bowls with excised designs. Because the paper-thin porcelain clay is so brittle, it can only be worked in the dry state and carving it requires extraordinary patience and delicacy. Of her 12 attempts at eggshell pieces, only three survived. The third, with "a beautiful, excised design of swans," was broken in Detroit on its way to an exhibition.

In 1910 Robineau was invited by Edward G. Lewis, founder of the American Women's League, to teach at University City Pottery at St. Louis, Missouri, and to work there with Taxile Doat. According to Paul Evans, "for a short time the University City Pottery had the most notable group of ceramic artists and experts thus far associated with an institution in this country." [5Paul Evans, Art Pottery of the United States, an Encyclopedia of Producers and their Marks (New York: Charles Scribners Sons, 1974), pp. 243-247. The American Women’s League, founded in 1907 to provide "wider opportunity for American women," sponsored correspondence courses and invited talented women to study under the personal instruction of the staff. The Women's League failed financially in 1911 and the Robineaus returned to Syracuse.] While there the Robineaus founded another magazine, Palette and Bench, under Lewis's sponsorship.

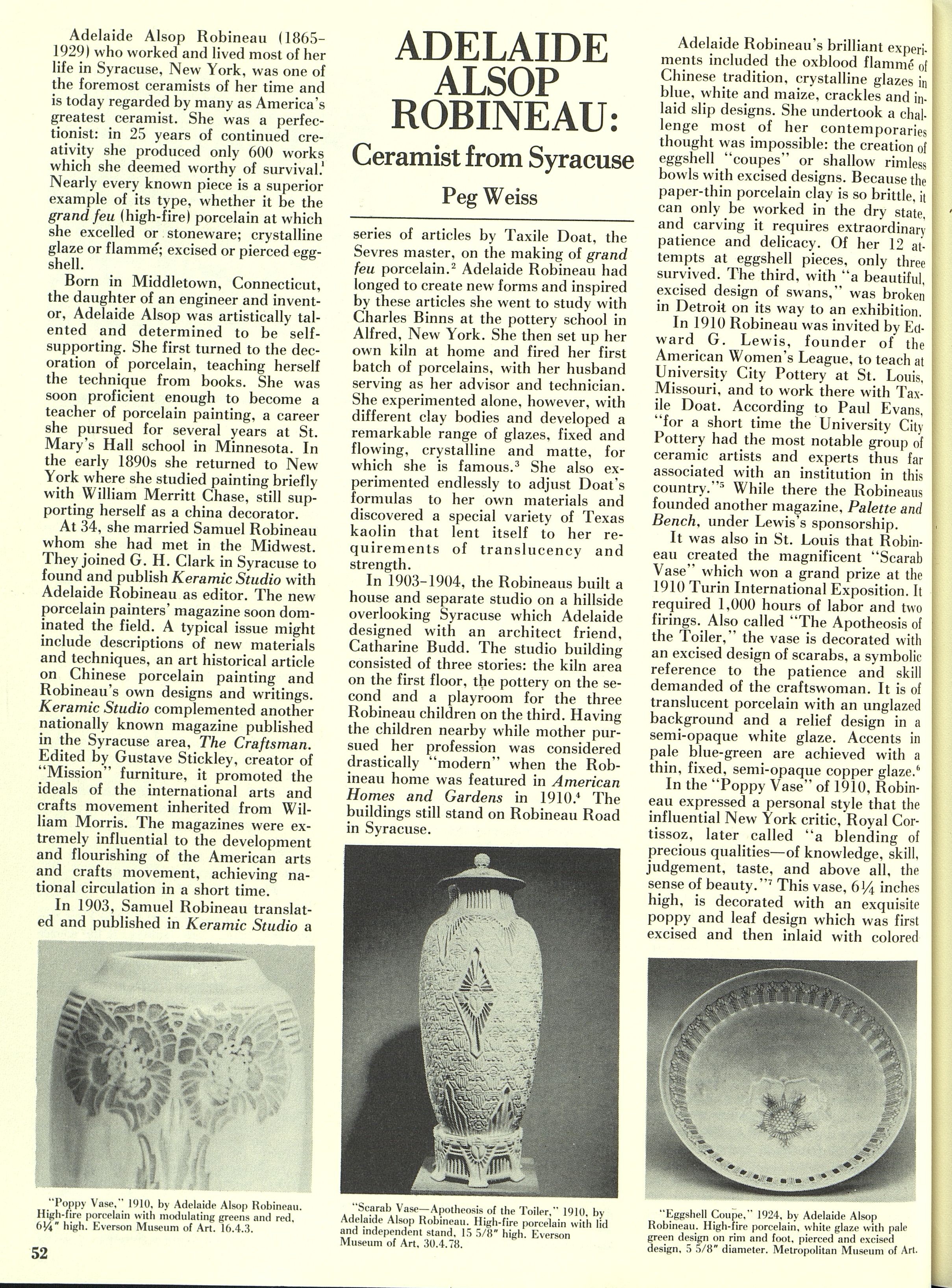

It was also in St. Louis that Robineau created the magnificent "Scarab Vase" which won a grand prize at the 1910 Turin International Exposition. It required 1,000 hours of labor and two firings. Also called "The Apotheosis of the Toiler," the vase is decorated with an excised design of scarabs, a symbolic reference to the patience and skill demanded of the craftswoman. It is of translucent porcelain with an unglazed background and a relief design in a semi-opaque white glaze. Accents in pale blue-green are achieved with a thin, fixed, semi-opaque copper glaze. [6Described in detail by Adelaide Alsop Robineau in an article on "American Pottery," The Art World, III (Nov., 1917), pp. 153-155.]

In the "Poppy Vase" of 1910, Robineau expressed a personal style that the influential New York critic, Royal Cortissoz, later called "a blending of precious qualities—of knowledge, skill, judgement, taste, and above all, the sense of beauty." [7Royal Cortissoz, New York Herald-Tribune (Feb. 24, 1929).] This vase, 6¼ inches high, is decorated with an exquisite poppy and leaf design which was first excised and then inlaid with colored slips. In the firing, the glazes remained perfectly set within the inlay, coloring and hardening to produce the effect of a transparent enamel over the whole. Small as it is, the vase has a monumental quality typical of Robineau's best work.

Another masterpiece is the "Viking Ship Vase" of 1905. With rich matte and semi-matte glazes of blue, green, brown and cream, the modest form is decorated with a typical Art Nouveau Viking ship motif, wave-tossed around its rim, a symbol of human transcendence over the vicissitudes of life. In a remarkable tour de force, the Viking ship motif is transformed from relief to sculpture in the delicately pierced, independent stand which supports the vase.

Vase after vase displays exquisite invention, from the subtle striations of the "Snake Bowl" with its delicate reptilian head, to the iridescent crystals of a small untitled white vase. Stylistically, the work ranges from restrained and elegant adaptations of Art Nouveau or arts and crafts movement taste to the orientalizing manner of the eggshell "coupes" to Art Deco urns.

Her work was so specialized and technically difficult that Robineau could not expect great monetary rewards. Whereas Louis Comfort Tiffany in New York and Lalique in France employed many workers and turned out multiple versions of their patterns, Robineau's creations were unique. Once in an attempt to increase her income, she tried to mass-produce porcelain doorknobs, but the endless repetition so frustrated and bored her that the operation ceased almost as soon as it began.

Nevertheless, she was richly rewarded by professional recognition during her lifetime. Her work was introduced to the public at the 1904 St. Louis Exposition and in 1905 Tiffany and Co. became an agent for the Robineau porcelains. [8See Paul Evans, also “Robineau Porcelains," Tiffany & Co., Agents, Fifth Avenue, New York (undated catalog, ca. 1907).] She was selected to exhibit at the Musee des Arts Décoratifs and at the Paris Salon in 1911, was awarded Grand Prize at the 1915 San Francisco Exposition, and received special prizes and awards from the Art Institute of Chicago and the societies of arts and crafts in Detroit and Boston. She received an honorary Doctor of Ceramic Science degree from Syracuse University in 1917 and in 1920 she joined the faculty. The Metropolitan Museum mounted an unusual one-person memorial exhibition of her work.

According to Samuel Robineau's accounting, she earned only about $10,000 from the sale of her work. Today it is considered priceless, a fact she anticipated in an hitherto unpublished letter:

"In the days of the ancient Chinese potters, Emperors paid fabulous prices for examples of their work, and nobility vied with each other to posess [sic] each piece which came perfect from the potter's hands. All through the ages kings and wealth have been patrons and eager purchasers of art crafts, not only of former times but of contemporary artists. It remained for grand America, who [sic] has been too busy just growing, to neglect contemporary and native arts and crafts so that no country is so lacking in native craftsmen and crafts work...they [the few patrons] have failed to see that contemporary talent has to be encouraged by purchase of the best in native work. [She expresses pleasure in Carter's interest in adding her work to the museum's collection and to encourage him and his board, she suggests the following]...as a simple matter of "boosting" Syracuse such a collection might be a drawing card. When a city wishes to be called to sit up higher in the seats of honor, like a good business man she would put her best foot forward, if she has anything above the average, she writes it in large letters, if she has anything unique, she blazons it abroad—Syracuse has at least two unique boasts to make—there is the salt which gives its savor—And there are the Robineau Porcelains!

She then suggested a purchase plan involving her own donation of some works as an incentive to the board of the Syracuse Museum, and concluded:

In this way Syracuse will have such a collection as no other museum will ever have the opportunity of purchasing even for double the amount. And when the Syracuse Art Museum [sic] is quoted in future articles as having fine example of the work of this or that artist it will be added that Syracuse's unique glory is its collection of the porcelains of its townswoman the only individual maker of art porcelain in this country, one of the few—the very few in the world and the only woman to attain such prominence in ceramics. All of which sounds very conceited from me but which is true nevertheless... [9Letter dated November 12, 1915, from Adelaide Alsop Robineau to Fernando Carter (punctuation and italics follow the original), in the archives of the Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, N.Y. Present plans for the Everson’s Robineau Collection include an exhibition of the complete collection in a new installation to be accompanied by a major catalog in 1979, the 75th anniversary of the introductior of Robineau’s work to the public at the 1904 St. Louis Exposition.]

Clearly, Robineau was not one to be easily deterred. Her tenacity and confidence in her craft was further shown in an article she wrote for The Art World in 1917:

This fascinating work unfortunately is not a paying proposition, but it has given me the satisfaction of doing original work, work which has not been done in this country before and may not be done again...I often dream of all the things I would have done if I had begun earlier in life or if I had been financially independent so that I could have devoted myself entirely to my porcelains. The pieces I have produced are few in number, but they represent in design and shape the best that was in me and I hope that some of them may be an inspiration to some artist of the future, who perhaps will be able to do more and better work than I have done. [10Adelaide Alsop Robineau, "American Pottery," p. 155.]

Adelaide Alsop Robineau need not have been so modest. Just as she predicted, Syracuse does consider her work one of its "glories." The Everson Museum still celebrates her memory in its regular Ceramics Exhibitions, inaugurated in her honor in 1932. Nearly half a century after her death she is admired by aspiring artists who covet the perfection of the "Poppy Vase" or "The Viking Ship," or one of the unnamed but brilliant crystalline-glazed vases. She was a high-fire porcelain maker, a "high-fire person" and an artist of the highest caliber.

Peg Weiss is Curator of Collections at the Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York, and Adjunct Professor in Art History at Syracuse University.