View the Issue

Read the Texts

Mexican Folk Pottery

Editorial Statement

The Aesthetics of Oppression

Is There a Feminine Aesthetic?

Quilt Poem

Women Talking, Women Thinking

The Martyr Arts

The Straits of Literature and History

Afro-Carolinian "Gullah" Baskets

The Left Hand of History

Weaving

Political Fabrications: Women's Textiles in Five Cultures

Art Hysterical Notions of Progress and Culture

Excerpts from Women and the Decorative Arts

The Woman's Building

Ten Ways to Look at a Flower

Trapped Women: Two Sister Designers, Margaret and Frances MacDonald

Adelaide Alsop Robineau: Ceramist from Syracuse

Women of the Bauhaus

Portrait of Frida Kahlo as a Tehuana

Feminism: Has It Changed Art History?

Are You a Closet Collector?

Making Something From Nothing

Waste Not/Want Not: Femmage

Sewing With My Great-Aunt Leonie Amestoy

The Apron: Status Symbol or Stitchery Sample?

Conversations and Reminiscences

Grandma Sara Bakes

Aran Kitchens, Aran Sweaters

Nepal Hill Art and Women's Traditions

The Equivocal Role of Women Artists in Non-Literate Cultures

Women's Art in Village India

Pages from an Asian Notebook

Quill Art

Turkmen Women, Weaving and Cultural Change

Kongo Pottery

Myth and the Sexual Division of Labor

Recitation of the Yoruba Bride

"By the Lakeside There Is an Echo": Towards a History of Women's Traditional Arts

Bibliography

Patricia Patterson

The island women love to talk but they seldom talk in aesthetic terms about the houses which are their medium and arena for a lifetime. They talk maliciously, sentimentally, tartly, and vividly about people, animals, crops, and weather, things that move and change. "Hasn't he a God-forsaken appearance?" "Nothing for it now but to put the thought of the evil day on the long finger." "You have two firm little ankle bones that'll walk you there and back again." Animated and daring while describing any event, living intensely inside their all-purpose kitchen, the chameleon like hub of Aran life, which changes constantly with each chore, meal and ceremony, Kate Conneeley and Nan Mullin treat their kitchens like their worn clothes, as things to be taken for granted. But the two crafts executed by Aran women, interior design and knitting, are decidedly legitimate art forms, each with its aesthetic devices, which could not have been developed anywhere except on this slab of rock twelve miles out in the Atlantic.

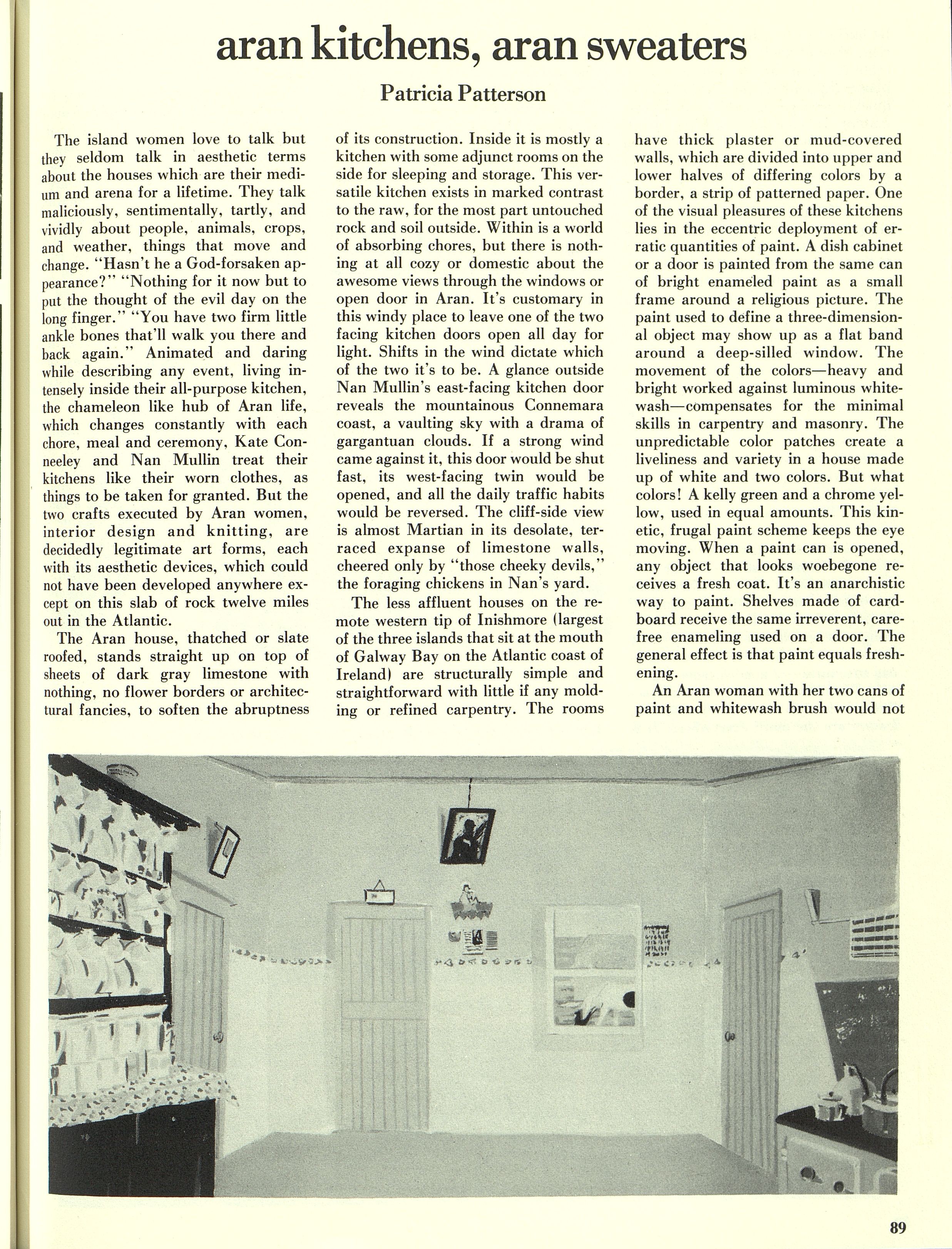

The Aran house, thatched or slate roofed, stands straight up on top of sheets of dark gray limestone with nothing, no flower borders or architectural fancies, to soften the abruptness of its construction. Inside it is mostly a kitchen with some adjunct rooms on the side for sleeping and storage. This versatile kitchen exists in marked contrast to the raw, for the most part, untouched rock and soil outside. Within is a world of absorbing chores, but there is nothing at all cozy or domestic about the awesome views through the windows or open door in Aran. It's customary in this windy place to leave one of the two facing kitchen doors open all day for light. Shifts in the wind dictate which of the two it's to be. A glance outside Nan Mullin's east-facing kitchen door reveals the mountainous Connemara coast, a vaulting sky with a drama of gargantuan clouds. If a strong wind came against it, this door would be shut fast, its west-facing twin would be opened, and all the daily traffic habits would be reversed. The cliff-side view is almost Martian in its desolate, terraced expanse of limestone walls, cheered only by "those cheeky devils," the foraging chickens in Nan's yard.

The less affluent houses on the remote western tip of Inishmore (largest of the three islands that sit at the mouth of Galway Bay on the Atlantic coast of Ireland) are structurally simple and straightforward with little if any molding or refined carpentry. The rooms have thick plaster or mud-covered walls, which are divided into upper and lower halves of differing colors by a border, a strip of patterned paper. One of the visual pleasures of these kitchens lies in the eccentric deployment of erratic quantities of paint. A dish cabinet or a door is painted from the same can of bright enameled paint as a small frame around a religious picture. The paint used to define a three-dimensional object may show up as a flat band around a deep-silled window. The movement of the colors—heavy and bright worked against luminous white-wash—compensates for the minimal skills in carpentry and masonry. The unpredictable color patches create a liveliness and variety in a house made up of white and two colors. But what colors! A kelly green and a chrome yellow, used in equal amounts. This kinetic, frugal paint scheme keeps the eye moving. When a paint can is opened, any object that looks woebegone receives a fresh coat. It's an anarchistic way to paint. Shelves made of cardboard receive the same irreverent, carefree enameling used on a door. The general effect is that paint equals freshening.

An Aran woman with her two cans of paint and whitewash brush would not be likely to win a home arts competition. Most of the items she uses to decorate her home are 80-cent purchases: plaster statuettes of the Virgin Mary or quickly put-together cardboard shelves. nothing to compare with the hand-painted wonders of the Pennsylvania Dutch. But the placement of these store-bought objects throughout the room is witty and innately elegant. Rooms dominated by a vivacity of language and dramatic physical gestures pick up sparkle from the stray spots of decoration, the luminous white walls, and the vivid shifting of wall levels. Except for the religious items, everything in the room is intensely handled: buckets, kettles and dishes. There is a natural flow between room decor and people. Objects with multiple uses seem fitting for a talkative people with a variety of skills. The stove is used for warming the room, washing and drying clothes, and cooking.

The Aran people either emigrate or stay put—nothing else. Life is controlled by specific facts of nature and history. The lack of trees, the phenomenal wind and rain, and the astonishing contiguity of the swarming, changeful life in the homes exist side by side with the somber Celtic and Christian debris (prehistoric forts, beehive dwellings of the saints, and Celtic crosses). Everything goes on within a cultural-psychic frame. Just as life is lived within rigorous structures—of a subsistence economy, Catholicism, no big city distractions, no birth control, no divorce—the frames are the motif everywhere. It is an island framed by water, framed by the Gaelic language; the mantel frames the coal stove or the hearth and is itself framed by a march of mementos and photos across its top.

Not even Mondrian lived more within rectilinear plasticity than the woman who boils, bakes, mends, churns, washes, sweeps, skims, and spiffs up her gridded workroom. The frame is used mostly as a definer, signifying "this is a door, this is the cupboard," setting off religious chromos with an inexpensive wooden frame. The placements, choice of objects, designing of the frame never seem off-handed, although the spatial judgments are never as precise as those made by the Shakers. Much of the architectural play is achieved by hanging frames at various levels, setting up a rhythm of unpredictable unions and divisions. There are three basic conventions for hanging pictures. The first is to hang the largest, always Jesus or Mary, about six inches from the ceiling, its top edge angled out from the wall. The second is to arrange groups in relation to the patterned divider which circles the room. The third convention relates objects to the doors and windows. A framed prayer, suspended by a string smack in the center above the door, does double duty, blessing the house and welcoming the visitor. None of the objects is placed only for decorative effect: these presences are like protectors spotted around...or connections. They create a stage set of cultural locators, defining the family's world as Catholic, Republic of Ireland, Gaelic-speaking, and their lineage as either Hernon, O'Brian or Concannon.

The most baroque object in any kitchen is the dish cabinet with virtually every piece of dishware owned by the family on display, exposed and handy. A flood of plates, mugs, jugs, saucers, cups (either plain white or bearing stripes or floral patterns), in an inordinate number of layerings, stackings, hanging spots and pattern changes. The mantelpiece is runner-up for most objects per square foot. Statues of the Virgin Mary, the Infant of Prague, small porcelain roosters, windup clock, battery-run radio, official portraiture: John F. Kennedy, Padriac Pearse (the Irish nationalist and poet), at least one pope, Pius, John or Paul, or St. Martin de Porres, a black saint who is a popular favorite all over Ireland.

The baroque condition of the mantel top and dish cabinet emphasizes the tendency of Aran rooms to throw all items into sculptural relief. The smallest item, a minute frame with a baby photo, a tiny white plastic statue of Mary, are tactically transformed by framing, color and placement, so that each item is emphatically present, a strongly defined object. The foot-and-a-half thick walls contribute a massiveness that is echoed by other hard-edge devices, the space divisions created by the borders are made more dramatic by the interplay of the cool luminous whitewash and the glossiness and hard insistence of the thick, brilliant, full-strength enamel. Some of the most enticing designs occur along the room's equator, an inch-and-a-half wall divider, a strip of paper with a flower pattern. Teasingly deployed with themselves and with the border are a potpourri of small articles: ceramic mementos, calendars, postcards, sentimental homilies and illustrated prayers. A souvenir plate just nudges the edge of a door frame, while its other side touches a prayer card which sits an inch above the patterned divider. These small gifts work as touchstones to the culture, but their minute echoing and alteration, one against the other, is endlessly enticing to the mind and eye.

While the Aran women may take their work as interior decorators for granted, they are proud, byedad!, of their sweaters and well aware of the art involved in making them. Sculptural (with a surface level varying as much as an inch), monochromatic and tight-fitting, these encrusted sweaters are meant to be worn in a harsh climate. Textures are coarse like the fissured and gashed surface of the island. Made of wool from which the natural oil has not been removed they're close to waterproof. They are so tight that they have buttons at the neck so that the head can get comfortably through. The close fit cuts down the possibilities of entanglement and interference, allowing it to be easily worn under a worker's jacket.

The patterns are arranged into clear representations of the island's physical terrain, with its staggering number of stone walls enclosing myriad tiny fields. The trellis, zigzag and diamond patterns crisscross the sweaters as walls cross the rocky island. Imagine a vertical row of diamonds enclosing a field of seed stitches with a bobble inside each of the diamond points, every diamond framed on its side by a band of cable stitches.

The sweaters are always a single color, usually a dark tweedy gray, indigo black or subtle browns with moss green or maroon casts to them. They possess an intriguing tone...nutty colors, like dark cinnamon or the shells of Brazil nuts. The women dress against the dourness of the island in bright primary colors, floral-print cottons and plaids; the men wear the colors of the landscape, brindled gray pants and sweaters, dark browns and dark blues, which harmonize with the stone walls, the fields, the sweep of limestone.

The names of the stitches and patterns refer to the trade of the men who originally wore them: the cable, rope, ladder stitch, the herring bone, triple sea wave, lobster claw, fishtail. These explicit names are different from the lyrical ones still used in Scotland, such as Sacred Heart, the Rose of Sharon, Star of Hope, Crown of Glory. But the Aran fisherman's sweater has its own biblical stitch, the Tree of Life. Originally, the sweaters were made by fishermen, a rather natural step from making and mending nets, weaving ropes and making knots. Now, and for an undetermined length of time, the women have taken over.

One of the finest knitters is Una Flaherty, a Bohemian spirit, her clothes held on by safety pins, who runs the shop in Bongowla, the last village on the western tip of the island. In between chasing chickens out of the open door, receiving a new shipment of goods from Galway with high-spirited witticisms and sarcastically getting tea for her husband Patrick, she knits. She has an energetic way with her works in progress, dragging them along the floor after her as she goes in search of a can of peas or couple of candles for a customer. An entertaining talker, she knits swiftly while carried away with her stories and suddenly throws her work to the floor to emphasize a point. Una's sweaters are exceptionally rich with interlaced designs, reminiscent of the patterning on Celtic stones and crosses.

Mary Flaherty, mother of nine, knits with amazing speed even while walking down the road with three of her youngest clutching at her skirts. Garrulous and multicrafted, these animated women live within a contradiction of clutter and simple geometry. In the rooms, the two most common design elements—frames and conscriptive devices which force the framed items into assemblies and groups—give the sense of rootedness, enclosure, a life of clear limits, a grounded life with few choices. Yet there are in both the sweater and kitchen design, contrary effects of intense, crowded together activity: the wildest puckishness within an economic pinpoint.

Kate Conneely’s kitchen was often transformed by a heady stream of language from Kate herself, her children and her cranky, bragging 87-year-old mother. A battery of kettles and pots were kept on the stove at all times. Shoe repairing, baking, butter churning. clothes washing, butchering, saddle mending, knitting. Often such activities required furniture to be shifted about and the room to take on an entirely different character. A heavy clothes washing called for the table and chairs to be moved out of the way, a massive amount of hot water boiled on the stove, the big tin tub moved in from the fields, sleeves to be rolled up and the floor to be doused with sudsy water. The long wall in the back of the house would be decked with clean wet sheets, shirts, underwear, trousers, pinafores, and these would have rocks placed on top of them so that the newly washed clothes would not blow away.

Two ancient grandmothers are stationed statuelike, in territorial possession of their spot in front of the fire. The population here, which includes animals welcome (dogs) and unwelcome (cats and chickens), is transformed during special occasions: dances with four accordionists, four or five singers taking turns between jigs, hornpikes, waltzes and polkas. During wakes, the corpse is laid out in the side bedroom and the kitchen is filled with people all night long.

Given the generations, needs, events of an Aran home, art is indeed not a central fact. As I was leaving, Kate said: "Patricia, it's a pity you're leaving now, because one of those two old ladies at the stove will be going soon. We'll have a great night here, that time." The two old women were nodding in agreement: "Yes, it’s a pity."

Life's conditions in the awesome stoneyard of Aran don't leave any apparent space for the visual arts. Yet, the cheapest item, as well as the most honored elder, gains "presence" by the way the women decorate the kitchens and design their sweaters. The intense, rectilinear use of space creates a fun, a garrulity, that is not unlike the famous Island talk. Wherever the eye lands, there is an elaborate fooling with decoration, intentional or otherwise.

Patricia Patterson is a painter and writes film criticism in collaboration with Manny Farber. She teaches drawing and painting at the University of California at San Diego.