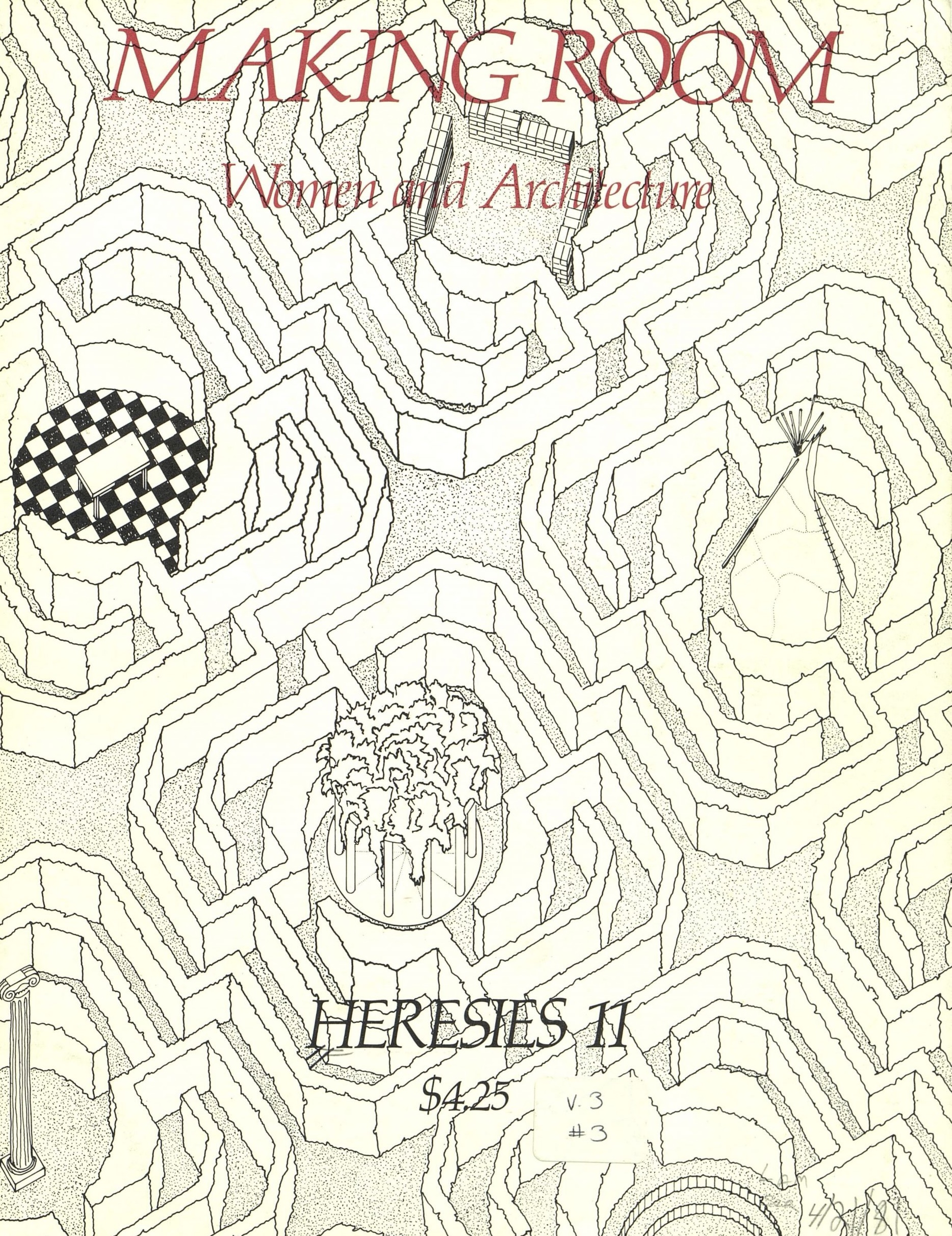

Making Room: Women and Architecture

Heresies Vol. 3, No. 3, 1980

-

-

Read the Issue

Explore Issue #11 in PDF format with full-text search or as individual entity-tagged TEI documents (coming soon).

The Issue 11 Collective

Editorial Collective: Barbara Marks, Jane C. McGroarty, Deborah Nevins, Gail Price, Cynthia Rock, Susana Torre, Leslie Kanes Weisman

From the Issue 11 Collective

The idea of a HERESIES issue examining the relationships between women and architecture was an outgrowth of projects and research which we had been engaged in collectively since 1976. Initially the proposal for this issue met with some skepticism both from the HERESIES Collective and other feminists. The feminist analysis of built space has come later than comparable critical evaluations of, for example employment, politics, health, and sex roles. This is no doubt related to the common belief that architecture is something only the wealthy can afford or that it is a neutral background which doesn’t affect people’s lives.

The notion of the Other, as understood by Simone de Beauvoir when she wrote about women as “defined and differentiated with reference to man,” as “the incidental, the inessential,” also applies to architecture. The history and practice of architecture have ignored, for all their lip service to humanism, the lives, needs, aspirations, work, and creativity of women. In this issue we refer to and expand on the humanist tradition of architecture through viewpoints, themes, and strategies that demonstrate how the connections between women’s lives and their environment are to a large extent a consequence of political and economic actions, both in a repressive and a liberating sense. Without these concerns architecture, as a profession and as an art, will utterly fail to fulfill its role in creating appropriate settings for all human life. The range of articles and projects selected for this issue are intended to open a debate and to create links between feminism and architecture, both in theory and in practice.

Women taking charge of their own spatial destiny is a theme of several articles and projects. Wekerle, Adam/Aitcheson/Sprague, Lindquist, S. Francis, Weisman, Harris, Marks/Bishop, and Sutton all describe a present-day self-help and community development movement in which women are working to define and fulfill their special needs, long ignored by developers, planners, and designers. Similarly, articles by Wright, Gilman, Hayden, and Rock show that in the past women have on occasion attempted to create alternative spaces for themselves, outside the limited sphere of the single-family home.

The powerlessness women feel in not being able to control their own environments as well as their frustration at being relegated to the domestic sphere come out in articles by Pollock and P. Francis. In different ways Rubbo, Barkin, and Cranz document how women frequently have not been asked to participate in spatial decision-making processes directly affecting their lives. All these authors underscore the difficulties women face in changing both their roles and their environments. The interior of the house has been the only area over which women have had any spatial control. An appreciation of women's creative responses to domestic confines and the identification of an ongoing woman’s culture in the home are themes taken up by Hess, Maglin, and Greenbaum.

Articles by Nevins, Balmori, Dietsch, and Boutelle focus on the work of women designers in the past and lead us to speculate about a female approach to design and career. Julia Morgan’s architectural practice owed much to a network of women clients and women’s organizations and can be seen as a consequence of the spirit of cooperation and enthusiasm among women which flourished during the Suffrage era. The work of Eileen Gray and Lilly Reich, European designers of the early modern movement, suggests a concern for human comfort and multiplicity of use which goes beyond the formal characteristics of the prevailing International Style.

Whether women design differently from their male counterparts seems to be a predictable question about women and architecture. While this HERESIES issue does not address this question extensively, certain articles and projects suggest that women do bring different attitudes to the design process (Rondanini, Kennedy, Birkby, Price, Connor/Dennis Rutholtz/Sung, Tsien, McNeur, Morris, Torre).

Even the most superficial examination of how the built environment is organized—how many and what kinds of services are available in what neighborhoods, who owns and who rents, who has spacious or cramped living and working quarters and where—reveals that the size, character, location, and quality of space accorded to an individual or class reflect the values of a society. Change in spatial allocation is therefore inherent to change in power distribution. We believe that what is broadly termed “architecture” indeed has a particular significance for women. As architects, designers, educators, critics, and feminists, we assert that a political interest in the design and planning of dwellings, communities, public spaces, and cities should be a concern of all feminists.

The Editors