View the Issue

Read the Texts

Mexican Folk Pottery

Editorial Statement

The Aesthetics of Oppression

Is There a Feminine Aesthetic?

Quilt Poem

Women Talking, Women Thinking

The Martyr Arts

The Straits of Literature and History

Afro-Carolinian "Gullah" Baskets

The Left Hand of History

Weaving

Political Fabrications: Women's Textiles in Five Cultures

Art Hysterical Notions of Progress and Culture

Excerpts from Women and the Decorative Arts

The Woman's Building

Ten Ways to Look at a Flower

Trapped Women: Two Sister Designers, Margaret and Frances MacDonald

Adelaide Alsop Robineau: Ceramist from Syracuse

Women of the Bauhaus

Portrait of Frida Kahlo as a Tehuana

Feminism: Has It Changed Art History?

Are You a Closet Collector?

Making Something From Nothing

Waste Not/Want Not: Femmage

Sewing With My Great-Aunt Leonie Amestoy

The Apron: Status Symbol or Stitchery Sample?

Conversations and Reminiscences

Grandma Sara Bakes

Aran Kitchens, Aran Sweaters

Nepal Hill Art and Women's Traditions

The Equivocal Role of Women Artists in Non-Literate Cultures

Women's Art in Village India

Pages from an Asian Notebook

Quill Art

Turkmen Women, Weaving and Cultural Change

Kongo Pottery

Myth and the Sexual Division of Labor

Recitation of the Yoruba Bride

"By the Lakeside There Is an Echo": Towards a History of Women's Traditional Arts

Bibliography

Jehanne H. Teilhet

Examine the claim: nonliterate art is a system of communication which manifests the ideologies and beliefs that bring order and definition to a person's culture. This statement seems fine, but who makes these art forms and whose view does the culture indeed reflect? I have come to realize that the arts, the hieratic arts in particular, reflect male behavior and opinion, for it is men who dominate the "important" arts. Women artists (and their art forms) play a more equivocal cultural role because they cannot work in certain materials or use specialized tools or technology and, in many cultures, cannot make figurative images. But we shall neither analyze nor interpret the role of the woman artist in nonliterate cultures until we have examined the role of the male artist.

Most of the documentation of nonliterate art assumes that only a man can be an artist. This man, depending on the cultural area, must possess talent, skill, intelligence and, on occasion, genealogical rights of privilege. Polynesia has a distinct class of professional artists to which one can belong only if one is born male and has the appropriate lineage and natural talent. In Melanesia talent and competitive skill rather than genealogy are the requisites for the coveted position of artist, but it is still only the male who qualifies. The men often serve an apprenticeship since the ritual meaning and knowledge of the objects they make are as important as learning the essential skills and exercising the necessary talent. In contrast to Oceanic cultures, in the Arctic it is generally believed that all male adults are able to make art. As Edmund Carpenter comments: "carving is a normal, essential skill [for the Eskimo], just as writing is with us." In Africa the position and training of the male artist ranges between the extremes of Polynesia and the Arctic.

Though the social status of the male artist varies in these societies, as do their artistic skill and training, the women have uniformly limited access to the art arena. Even in societies such as that of Polynesia, where they have political and economic importance, women work in "barkcloth and weaving, but the important hard-media crafts [are] the preserve of men." In Melanesia, where the political and economic power lie mainly in the hands of the "Big Men," women work in pottery and weaving. In many African cultures, the Yoruba of Nigeria for example, women can achieve political and/or economic importance and are not entirely excluded from ritual, yet "the women do the spinning, dyeing, matting, and the potting; and the remainder of the crafts are practiced by men."

Douglas Fraser points out that "primitive man," though he may not have a word for "art," "almost always differentiates between objects produced by a slow, repetitive process, such as weaving or pottery (crafts), and other objects of paramount significance for his culture. He relegates craft work to inferiors (i.e., women); only men, as a rule, practiced carving and painting." Fraser's observation is accurate, but Andrew Whiteford, in response to Fraser, raises the question of whether the crafts made by women can be considered, from a Western perspective, any less an art form than the "art" made by men. In reference to American Indian cultures, Whiteford writes:

‘"That one type of painting is realistic, religious, and male-produced, while the other is geometric, secular—although it may have religious connotations we do not know about—and female-produced does not suffice to put them in different categories. If we insist upon separating them, we are led to the disparaging conclusion that Indian men created sacred art: women only manufactured mundane crafts."’

Our aesthetic and cognitive response to these art forms made by women is often different from the response in the cultures that produced them. We may indeed designate many of the objects made by women as "art." But we must realize that we differentiate between "art" and "craft" in terms of ideas of "innovation," "creativity" and "significant form;" by strict Western definition most nonliterate arts would then fall into the category of craft. This distinction between art and craft by Western standards is thus an arbitrary one when applied out of context to nonliterate art: women artists are neither more nor less innovative and creative within the media they use than are men artists.

"The specific difference between the artist and non-artist seems to be one of degree. This is more obvious in a non-literate, or so-called primitive society, than in our own. In pre-European Hawaii, for example, nearly all women made bark cloth called kapa (tapa), decorating it with highly creative designs. In a broad sense most of these women were artists, some better than others, for some examples of tapa display more intuitive inventiveness and mastery of technique than others."

Many nonliterate cultures distinguish between what might be called secular, utilitarian objects and religio-political, status objects. The latter are classified either by their use or their A Samoan woman from Vailoa village showing the author a tapa cloth she has just finished. The bark cloth is used in their homes as room dividers and decoration, and they also give tapa-cloth gifts to people building new homes, as a kind of house-warming gift. (Savaii, Samoa, 1972) ritual process of manufacture, or in some cases, by a finer quality of workmanship. For example, in the Marquesas, a serving bowl not made by a male artist with deep knowledge of magic and ritual would be just a bowl because it had not been properly initiated into the Universe. Both men and women produce secular objects, but in most cultures it is the expert male artist who usually works on the culturally determined, more important "art" objects. (We must remember that it was the Western world—mainly via male anthropologists and art historians—that introduced the concept of "art" to nonliterate cultures, and determined what would qualify as "art," with until recently, little corroboration from the indigenous people themselves.) The issue here, however, is not whether we accept the objects produced by women as "art," but why most women were and are traditionally denied access to the specialized role of artist as creator of religio-political objects. The relevant factor is that however art is defined, all nonliterate cultures distinguish between the "art" produced by men and that produced by women; and this is our concern here.

The disparities of style, technique and media between men and women artists appear to be universal. In most cultures women are rarely allowed to make anthropomorphic or zoomorphic forms; these are the prerogative of men. In most cultures women are rarely permitted to make objects requiring the knowledge of ritual process or the skill and knowledge of manipulating certain specialized tools. And there seems to be a universal taboo against women's sculpting in hard materials such wood, bone, ivory, stone, gold and metal compounds; these materials are used exclusively by men. Women can work only with soft, malleable materials: clay, gourds, basketry, leather or weaving. We can therefore say that a distinction exists (in traditional nonliterate societies) between the arts made by men and women.

Franz Boas has commented that the stylistic differences he observed in an Eskimo community arose both from differences in the technical processes and (even more) from the fact that men do the realistic work and women the clothing and sewn leather work. William Bascom pursues Boas's notion that a sexual division of labor must also be considered in regard to stylistic differences:

In painting, for example, there are marked contrasts between the representational designs of men and the geometric patterns of women among the American Indians of the Plains and the Great Basin; and the same is true in bead-working. Among the Ashanti and the peoples of the Cameroun grasslands, the anthropomorphic pottery pipes made by men contrast sharply with the pottery produced by women.

He has also noted that artists divided within a society by sex and/or craft may develop distinct styles, just as isolated subtribes do. Both Boas and Bascom address the broad issue of distinct styles within one society, and each notes that when the men and the women work in the same medium their products are markedly distinguishable. Robert Rattray, working among the Ashanti of Ghana, also notes this distinction: "Men do not fashion pots or pipes unless they represent anthropomorphic or zoomorphic forms, for women are forbidden to make these." Such a distinction is also observed among American Indians: Whiteford found that women's art, excluding tourist art, rarely portrayed animal and human forms. The media shared by men and women are also distinguished by technique or process. For example, Yoruba men and women both weave. The men use a horizontal, narrow band loom. The women, however, use a vertical cotton loom. Men may have adopted the horizontal loom because it can produce an endless strip of cloth, thereby relegating the more restrictive or "inferior" process of the vertical loom for the women. Roslyn Walker, however, suggests that the women's use of the vertical loom is "a practical distinction," since the vertical loom is not placed against the abdomen and allows a woman to continue weaving during pregnancy. Her argument is not compelling since women are only pregnant for a few years of their working life.

Anthropomorphic and zoomorphic forms are usually reserved for the more important or sacred religio-political representations of deities, ancestors and benevolent and malevolent spirits or divine personages. One might conclude that women are restricted from making these forms because of their powerful association with the supernatural. But, among the Anang of Nigeria and other societies, human and animal figurines are used as house decorations and toys. Since these figures are purely secular, we might question why women are not allowed to make them. Women cannot make them because they are carved in wood; they would probably be allowed to make a rudimentary toy figure in clay. But as women do not generally make these images they would not necessarily be able to make even a clay figure, so it is not surprising to discover that women do not try. In the final analysis, one must conclude that anthropomorphic and zoomorphic forms are of such paramount importance that making them is a privilege given almost exclusively to men. There are exceptions to this restriction: certain women have extraordinary talents and skills not unlike a shaman, for which particular societies make allowances. I will return to this point later.

Certain oral traditions relate how women once made anthropomorphic images. One such story is reported by Rattray. The Ashanti people told him about a potter, Denta, who became barren because she modeled "figure pots." Thereafter, according to the Ashanti, women did not make highly ornamented pottery. Rattray was also told that women were forbidden to make anthropomorphic forms because they required greater skill. (In connection with the grave punishment of becoming barren, Ashanti women are forewarned that they do not have the greater skill, which implies the skill of ritual knowledge.) Little literature is available relating specifically to the prohibition against women's making anthropomorphic or zoomorphic forms, but of the accounts that I know, women who initiated the making of such images were either killed, sworn to secrecy or made barren. That some women initially created figurines may relate to their innate role as natural creator of anthropomorphic forms. Adrian Gerbrands writes: "... it is no wonder that the woodcarver, the maker of wooden images, has a special place in the Asmat society. Just as a new human being develops in the body of a woman, so does wood come to life in his hand. His creativity, however, belongs to another sphere. From the woman comes the life of this world, whereas he creates supernatural life. One might also argue that women, as creators of human beings, had no subliminal need to create anthropomorphic representations. But if that were the case, men would not have thought it necessary to restrict the women's imagery. One could surmise that women, with their innate powers to give birth in the real world, were already too powerful and to balance that power men took as their prerogative the right to create supernatural life in the forms of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic images.

Some women, mentioned above, are allowed to make anthropomorphic and zoomorphic forms in soft materials such as clay. A survey showing the cultural distribution of these women has not been compiled. Women in Melanesia (i.e., Wusi, New Hebrides, and the Chambri lakes district of New Guinea) and Africa make figurative images in terra cotta. Robert Thompson, in his article "Abatan: A Master Potter of the Egbado Yoruba," gives us an excellent portrait of a woman artist. Both Abatan's mother and maternal grandmother were potters. Unlike male artists, she had no formal training. She learned her technique and inspiration from the constant observation of her mother. Abatan is known for her figurative vessels (awo ota eyinle), a vessel for the stones of Eyinle, a Yoruba god with "an amazing synthesis of powers of the hunt, herbalism, and water." Abatan's "parents believed that she came into the world through the grace of Eyinle. Accordingly, as an invocation, she received the name of the deity before his transformation, Abatan... As the senior member of the cult of Oshun and Eyinle at Oke-Odan, Abatan lives a life of prestige, balanced just short of hauteur..." Thompson stresses the fact that Abatan is a women artist of stature among the Egbado Yoruba. She is not an ordinary woman, she has religio-political and economic status. But had she not been born the daughter of a potter and not come into the world through the grace of Eyinle and not been talented, she would not have had the opportunity to make figurative pots and accrue status. This safeguards the making of figurative images from incursion by just any woman.

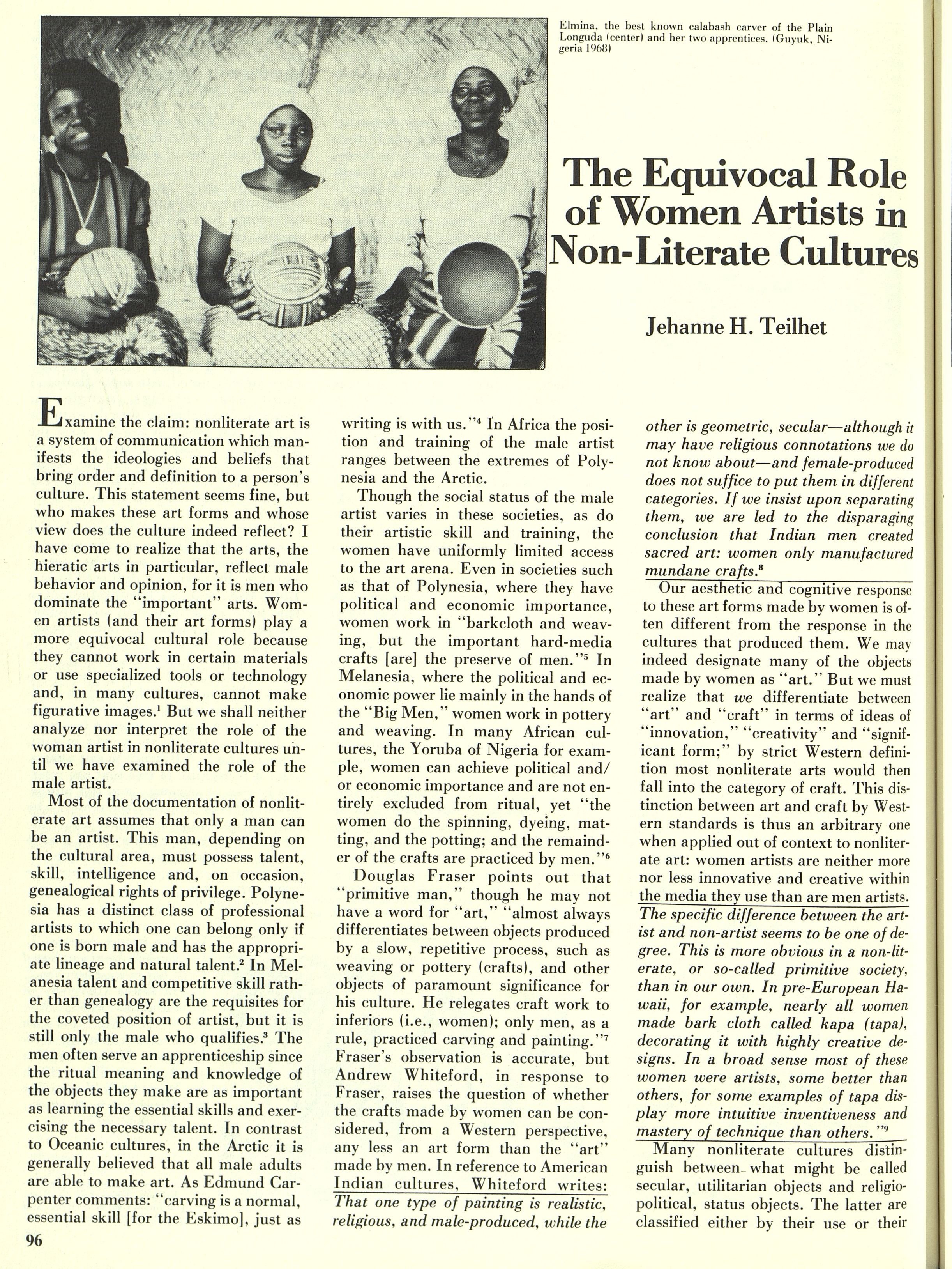

Among the Plain Longuda of Nigeria, certain women are allowed to make anthropomorphic and zoomorphic pots for the Kwandlha cult. The master of Kwandlha must be an artist as well as a healer, for the spirits of diseases will not take up their abode in poorly executed Kwandlha vessels. Dasumi, of the village of Guyuk, is respected for her knowledge and skill in making the Kwandlha pots. She is woman past child-bearing years, and unlike Abatan, she did not inherit her position. In the early 1960s Dasumi was plagued with a series of illnesses; she went to Moudo, an elderly woman living nearby, to be cured. Moudo told Dasumi that the Kwandlha were worrying her, they were calling her to be come a member of the cult. Dasumi apprenticed with Moudo for about two years before she became a master of the Kwandlha.

Dasumi specializes in children's diseases; when a child is sick, the mother will consult Dasumi. She examines the child and then takes one of her diagnostic Kwandlha pots from their own special hut (tanda Kwandlha). If the particular Kwandlha stays submerged in a basin of water, then her diagnosis is correct; if not, she will take another Kwandlha and repeat this process until one stays submerged. The child is given some medicine and the mother gives Dasumi some of the special red clay required to fashion a Kwandlha. Dasumi will touch the child's body with the red clay, beseeching the spirit of the disease to leave the child and acknowledge that she will be making an abode for it. In seclusion Dasumi will create, with the coil and mold method, a Kwandlha pot that personifies that disease. Gurguburile, for example, is a pot given a human form: the feet are the base of the pot, the legs, arms and belly make up the body of the pot, the neck is the neck and the open mouth of the head is the mouth of the pot. Gurguburile is covered with festering sores, one arm is eaten away and the other holds a calabash for water. This anthropomorphic pot is used to cure leprosy.

Upon completing a pot, Dasumi gives it to the mother to sun dry for four days before firing. Once fired, Dasumi returns to begin the ritualized process of calling the spirit of the disease to leave the child and enter the Kwandlha; this entails a special Kwandlha language, the sacrifice of a chicken or goat and a special drink called Sinke contained in a special terra-cotta urn, Suthala. Dasumi is paid in kind or coin for her work.

Though Dasumi works within an iconographic tradition, she is allowed to introduce new elements as long as it pleases the spirits. She was, when I interviewed her in 1968, more famous than Moudo, her teacher. My informant, Elam Robaino, attributed this to her artistic skills as a maker of Kwandlha pots. The spirits of the diseases are pleased with her pots; they like their abodes.

I asked Dasumi if men made Kwandlha pots; she replied that a man in Purokayo village, some four miles from Guyak, makes small ones for children. There is also an old man in Kuryi village who makes Kwandlha from wood, but it takes him much time to do it. She added that her grandson, who was three, seemed to have a calling for the Kwandlha; her daughters were not called to the profession.

Both Dasumi and Abatan were called to their particular cults and both proved to have the necessary artistic skills to make figurative vessels; one inherited the profession, the other apprenticed. Of equal importance is the fact that their own society made allowances for women of unusual talent to enter the male domain of the figurative arts.

Lacking sufficient data from other societies, one can only conjecture that the tradition of making figurative imagery is open, in certain societies, only to exceptional women—women who cross the boundary between the sacred and profane.

More universal in its application is the taboo against women's working with hard materials and certain specialized tools. Although terra-cotta in comparison with wood is a relatively permanent medium, the women work this medium when it is soft and malleable. That it is transformed when fired into a relatively hard and durable substance does not appear to be an issue.

The hard materials used as a primary medium by male artists are usually rated in most nonliterate cultures according to their relative importance. The scale of relative importance, power or sanctity of the medium varies from culture to culture, but the culturally defined criterion is generally determined by the material's durability, scarcity, the skill and/or technology necessary to work it and the medium's innate magico-religious properties. As a general rule, the more important materials are reserved for the more important deities or supernatural forces. Among the Yoruba, wood is rarely employed to represent the gods because of its perishable nature. Wood is used, however, for votive sculpture representing priests or devotees. To the Asmat, who live in an alluvial mudflat that lacks stone or metal ores, wood becomes the important medium. Wood is so important in this culture that man and tree are regarded as interchangeable concepts: the human being is a tree and the tree is a human being. That wood is a "mortal" living substance can enhance its value as a symbolic referent, as intimated by the Asmat man/tree equivalent. In cultures that have a variety of materials to choose from, one also finds, as with the Yoruba, that the mortal-decaying aspect of wood relegates its use to the more human realms associated with ancestor spirits, culture heroes and demigods, as well as priests and devotees. Because of its accessibility and the varying skills of adeptness cessary to carve it, wood is a popular medium in nonliterate cultures.

Stone is valued for its durability, its magical origin and the skill necessary to carve it. Many nonliterate cultures have access to stone, but few utilize its potential (as sculpture in the round in contrast to petroglyphs)—possibly because they lack the tools and necessary knowledge to carve it. Polynesians knew how to work stone (volcanic tuff), but none achieved the monumental scale of the Moai on Easter Island. African artists worked in stone, but few if any today carry on the tradition of their forefathers.

Where stone is worked extensively, the stone (like wood) is graded in importance. To the Canadian Eskimos, for example, hardness is more important than color or shininess; only the weaker and less competent Eskimos carve soft stone which is "jokingly referred to as 'women's stone.'"

The hard, white ivory of the walrus tusk is still the Eskimos' favorite material. "The desire to use ivory as an adjunct to stone carving is powerful in nearly all areas, whatever the nature of the local stone." As Nelson Graburn explains, the ivory is desired for its maleness. The forward thrust of the natural form is associated with male assertion. It should be noted that with the introduction of the tourist market, women have been encouraged to carve. But the women only carve occasionally and "they do not seem to have impressed their values on the activity."

Whale ivory was also valued in Polynesia; in Hawaii the whale ivory (lei niho pałaoa) necklace was tapu to all except the chief (alii). In Melanesia pigs' tusks are highly valued as are elephants' tusks in Africa. In former times, elephant ivory could only be possessed and used by the divine chief (Oba) of Benin, Nigeria. In addition to the given, man-defining metaphor of that particular ivory-bearing animal or mammal, the form, color and density of the ivory enhances its symbolic reference to the male genitalia. Ivory carved or in its natural state, always signals important religio-political concepts. Bone, human or otherwise, is also an intrinsic carrier of religio-political concepts.

Metals, because of their permanence and technical manufacture, are an esteemed material. Though the cultures of Oceania did not manufacture metals, they were quick to trade with Europeans for this desirous material. Among the Gola of Liberia, "the skill of working with metals was considered one of the most mysterious and remarkable forms of knowledge in the traditional culture." The traditional bronze or brass casters and the blacksmiths of Africa are often distinguished in that the former are creators of "art" objects and the latter creators of secular objects, such as tools and weapons. Both can, however, create art forms; both belong to a separate caste, guild or disjunctive social group signaling that both have "mysterious powers" in connection with the process of manufacturing metals. That the working of metals is a male prerogative also refers to the use of metal objects in war and hunting. Precious metals such as gold and silver reflect the splendor and panoply of the conjoined realms of man and god.

The above is not an exhaustive survey of hard materials, but it gives a summary view of the values and ideologies men have attributed to certain materials. In short, it seems that men have come to identify their maleness with materials they have explicitly or implicitly chosen as their exclusive prerogative. Women work in soft materials that "best" reflect their femaleness. In comparison with hard materials, these are generally less enduring, fragile, more pliable, secondary or subservient, common and secularly oriented to women's work: i.e., the home, garden. cooking and childraising. Originally there may have been little or no status differentiation between the media; that is, the men's materials were not necessarily better than the women's materials, until a conscious effort was made to give certain materials qualities of status and importance. It is plausible that women initially had less leisure time than men did and therefore turned their creative talents toward the materials close at hand to make the objects necessary for domestic life, without identifying with the material. But as sex roles became more defined, the artmaking habits developed into political moves, and the material that the men initially worked in was given an imaginary power to justify male seizure of power and status over women. I believe the values and ideologies attributed to certain materials were a male invention to keep women in their place because I find it curious that women did not choose to explore the use of different media once the society became more settled. Evidence in fact indicates that women must have tried to work in other materials, otherwise there would not be so many tapus against women achieving this goal.

In traditional cultures men have controlled women's use of materials by not allowing them to use the tools necessary to work hard materials. In many nonliterate cultures the artist's tools are somewhat animistic; they are thought to possess intelligence, given their own family names, and in some areas, such as Polynesia, their own genealogy. Tools can accrue prestige, power and sanctity, for it is the conscious, conjoined effort of tools and men that create carvings. Carving is a religious act; among the Ashanti and other African societies, sacrifices and prayers were made to the tools to ask them for their assistance and freedom from accidents. In Hawaii the artist "consecrated his tools by a sacrifice and a chant to insure that sufficient mana was contained in them, consequently insuring the efficacy of the image, 'the house of the god.'" By ritualizing the artist's tools, women were barred from using them because, as sources of pollution, women would nullify the tools' efficacy. Women were also handicapped in that they could not work in the hard materials necessary to make their own tools. By restricting women from using specialized artistry, tools or technology, men have safeguarded hard materials for their own use. Many scholars have commented on the fact that "the act of carving should exhibit those qualities central to the male hunting and sex role." Tools and technology in the hands of women would cause an imbalance in the equipose of sexual labor.

In addition, a certain cosmology often clearly ordains the privilege of carving to men. In the Anang society we are told that women do not carve because the Creator God, Abassi, "wills it and has instructed the fate spirit not to assign the craft to a female." In New Ireland there is a legend that the first woodcarver learned his craft from a ghost. The woodcarver instructed students who then became famous artists. Women were not only excluded from art and ritual, they could not even see the objects or use the sacred word for them, alik or uli, on threat of being choked to death by men.

For the "important arts" men have developed an elaborate process of manufacture regulated by a prescribed set of rituals. The special, prescribed actions, repeated over and over again, lend continuity and stability to the ritual. These formal actions, sanctioned by religion, are thought to have an esoteric importance which is only fully comprehensible to the initiated male artists. Rituals have many levels of significance, but it is possible that the ritualization of the art process developed, in part, as a further precaution to prevent women from entering this domain. Women have rituals of their own and in some cases are allowed to join the men's rituals, but women do not have a prescribed set of ritualized actions in the creation of their arts. Even though Abatan and Dasumi worked in the realm of the supernatural, made figurative images, and, in the case of Dasumi, used a special red clay, thein artistic processes were not ritualized. This signifies that women's artistry deals with the more profane real time and space.

The ritualized making process has many variants among nonliterate cultures, but the majority, if not all, share the belief that women are sources of pollution. Strict precautions must therefore be taken to exclude women from these ritualized activities. In Polynesia tapus of unsacredness "were associated for the most part with women, to whom dangerous spirits were likely to attach themselves, and who were at times in a contaminated state psychically; and with sickness and death which were the signs of the presence of fearful demons." This equation is present (in varying degrees) in other nonliterate cultures, and an important aspect of the ritualized artistic process is to purify and protect the male artist from malevolent forces, which include women. In all nonliterate cultures the most dangerous form of pollution is connected with menstrual blood. Menstrual blood was regarded among the Maoris of New Zealand as a human being manqué. The Mbum and Jukun of Nigeria segregated menstruous women because the household gods found the menstrual blood abhorrent. An Ashanti "woman might not carve a stool—because of the ban against menstruation. A woman in this state was formerly not even allowed to approach wood-carvers while at work, on pain of death or of a heavy fine. This fine was to pay for sacrifices to be made upon the ancestral stools of dead kings, and also upon the wood-carver's tools." Rattray believes that the abhorrence of the unclean woman "is based on the supposition that contact with her, directly or indirectly, is held to negate and render useless all supernatural or magico-protective powers possessed by either persons or spirits or objects. Even by direct contact, therefore, an un-clean woman is capable of breaking down all barriers which stand between defenseless man and those evil unseen powers which beset him on every side." This belief, with subtle variations, is common to all nonliterate cultures.

Not only is there a tapu against menstrual blood, but, in addition, most male artists have to abstain from sexual intercourse because they believe it has an adverse effect on their work. In Oceania sexual intercourse can endanger or nullify a carver's mana. In Africa an Anang carver will not have sexual intercourse the night before he begins an important carving because his work is impeded. "Too many acts of intercourse is thought to weaken him for a day or two, inhibit his desire to carve and his creative impulse, cause him to shape his pieces poorly, and lead him to cut himself." The carver's fear of wounding himself, of bleeding, is a prominent concern which can relate to punishment, death and menstrual blood. Equally common is the belief that should the wife be unfaithful, without her husband's knowledge, his tools will cut him when he goes to carve.

Warner Muensterberger (1951) was the first, to my knowledge, to address the issue of women's exclusion in the arts of nonliterate cultures. His article emphasized why men felt it necessary to exclude women from the major art-making processes. In summing up he writes:

The overanxious exclusion of women discloses the regressive tendency involved. The artist relinquishes communication with an inhibiting or disturbing environment. Women are phobically avoided...The regressive tendency for isolation is a security measure. Affect is being avoided. Objective reality is denied while strength is gained from the narcissistic retreat to a level of omnipotent fantasy...If these are the conditions under which artistic activity among primitive peoples is possible, then two seemingly contradictory tendencies are at work: the necessary isolation indicates that distance from the oedipal mother is sought. The menstruating woman is avoided or even dangerous. On the other hand, reunion with the giving mother of the preoedipal phase is wanted.

Muensterberger's Freudian interpretation is one viewpoint on the seemingl universal exclusion of women in the arena of "important arts." There are however, other ways to examine this phenomenon.

The paradigm for the ritualized process of man's creations may be found in the cultural behavior of women during their menstrual cycles, pregnancy and childbirth. When men work on important objects, they usually do so in seclusion or with other men of status. And should they carve in the sanctuary of the men's house, this interior is often referred to as the womb. When women have their menstrual period they usually move to a special house of seclusion or some equivalent; and in many cultures there is also a special childbearing area. In these situations both the men and women are, in effect particularly powerful, negatively or positively, and must be removed from the realm of the ordinary. During the process of creation, both men (creating important objects) and women (creating human life) are subject to specific tapus imposed upon them for their own and their creation's protection and the implied protection of others. These restrictions vary from culture to culture, but vulnerability in creation is common to both men and women in all nonliterate cultures. If the tapus are broken, men may cut themselves with their tools, miscarve a spiritless object or even die; women may miscarry, give birth to a dead or deformed child or die in labor.

Analogous to this concept is the Polynesian belief that a new (art) object is comparable to a newborn child.

Like the child, the canoe, house, or other object had a soul and a vital principle that required strengthening, for all objects were conscious and animate...It is evident that the new object, as a living being, needed the same kind of rites to free and protect it against evil and to endow it with mana and other necessary psychic qualities, as did the human infant.

In looking at other nonliterate cultures we can find parallels between the "consecrating" of "important" objects and the consecration ceremonies for children, particularly the male infant.

A final point concerns the "creativity" of male artists. George Kubler writes: "Many societies have accordingly proscribed all recognition of inventive behavior, preferring to reward ritual repetition, rather than to permit inventive variations." Under different situations, inventive variations can and do occur, but in the main, the ritualized art process constrains innovation and free self-expression. Hieratic art emphasizes repetition and encourages clever and ingenious manipulation of the iconographic elements within a given iconography. Because women do not have their own ritualized process of art-making and their art is not hieratic, it follows that women artists can be more innovative and more self-expressive in the arts than men. Women, however are restricted in their use of materials and lack of specialized tools, but as typified by the work of Abatan and Dasumi, they have a great deal of freedom in the way they interpret the existing iconographic elements and add on new, inventive iconographic elements. I suggest that the style and technique of the arts produced by women is a better indicator of the society's changing notion of aesthetics than that of the arts produced by men. The objects made by women are used by everyone: as the culture's aesthetic norm changes, the women's art is the first to reflect this since these arts are nonhieratic. In the hieratic arts of men, an innovation conjoined with an aesthetic change introduces a state of anxiety as the artist's risk factor is high. To introduce an innovative form, the male artist risks his religio-political status. He risks offending the supernatural realm and the ruling chiefs. Male artists who do not work within a ritualized process and are not making hieratic art are apt to be the ones with lesser ability and are therefore not as reliable as a source of aesthetic notion.

It appears, then, that women are believed to have greater innate powers than men. Women have the power to create and control life. They control life through death as signified by the menses and abortion. Without children the family lineage dies, as do all the ancestors who live in the supernatural world. The continuity between the present and the past is broken. Women are feared and respected for their creative powers. Conversely, women who are barren lose status; in nonliterate cultures a barren woman is undisputedly grounds for divorce.

To balance women's innate powers, men have created external powers that slowly became steeped in ritual and ceremony and sanctioned by the authority of the supernatural realm. Women, in the main, were excluded from the rituals of men and more or less constrained in their economic and political power. There are exceptions, including those women past child-bearing age who are viewed as "men" among women. The male artists rival the women's innate powers as both are in the position to manipulate the forces of creation and continuity.

How and why women were relegated to the less important arts is a gray area of conjecture; I do not believe it is a question of female preference. Rather, it is likely that the dominant male group has claimed the hieratic arts for itself consistently: the men make them because they are important and they are important because the men make them. Should the less dominant group (which shall remain unspecified) do something valuable, then the men will adopt that too. It has been a zero-sum game of distribution. The hieratic arts became instruments to articulate meaning structures and problems; in addition they were a powerful way to control women. Male hieratic art has been promoted in general by males to maintain their own importance. It is no wonder that men, particularly in nonliterate cultures where women have achieved prominence on political, economic and even religious levels, have rarely, if ever, allowed the women to create the "important" arts. The old belief systems bound by tradition are hard to break, as witnessed by the scarcity of contemporary women artists from the third world.

In Surinam, the Aucaner women carve in soft materials, calabashes. What is unusual is the fact that the women only embellish the interior of the calabash. (LokoLoko village, Surinam, 1975) 102

*I wish to acknowledge Robert Elliott Moira Roth, Melford Spiro and especially David Antin and Zack Fisk for their critical comments on this paper.

Jehanne H. Teilhet is an art historian on the faculty of the University of California at San Diego. She has done fieldwork in Africa, Oceania and Asia and was curator of exhibitions at the La Jolla Museum and at the Fine Arts Gallery in San Diego. She is currently working on a Gauguin exhibition with Seibu in Tokyo.