View the Issue

Read the Texts

Mexican Folk Pottery

Editorial Statement

The Aesthetics of Oppression

Is There a Feminine Aesthetic?

Quilt Poem

Women Talking, Women Thinking

The Martyr Arts

The Straits of Literature and History

Afro-Carolinian "Gullah" Baskets

The Left Hand of History

Weaving

Political Fabrications: Women's Textiles in Five Cultures

Art Hysterical Notions of Progress and Culture

Excerpts from Women and the Decorative Arts

The Woman's Building

Ten Ways to Look at a Flower

Trapped Women: Two Sister Designers, Margaret and Frances MacDonald

Adelaide Alsop Robineau: Ceramist from Syracuse

Women of the Bauhaus

Portrait of Frida Kahlo as a Tehuana

Feminism: Has It Changed Art History?

Are You a Closet Collector?

Making Something From Nothing

Waste Not/Want Not: Femmage

Sewing With My Great-Aunt Leonie Amestoy

The Apron: Status Symbol or Stitchery Sample?

Conversations and Reminiscences

Grandma Sara Bakes

Aran Kitchens, Aran Sweaters

Nepal Hill Art and Women's Traditions

The Equivocal Role of Women Artists in Non-Literate Cultures

Women's Art in Village India

Pages from an Asian Notebook

Quill Art

Turkmen Women, Weaving and Cultural Change

Kongo Pottery

Myth and the Sexual Division of Labor

Recitation of the Yoruba Bride

"By the Lakeside There Is an Echo": Towards a History of Women's Traditional Arts

Bibliography

Elli Siskind

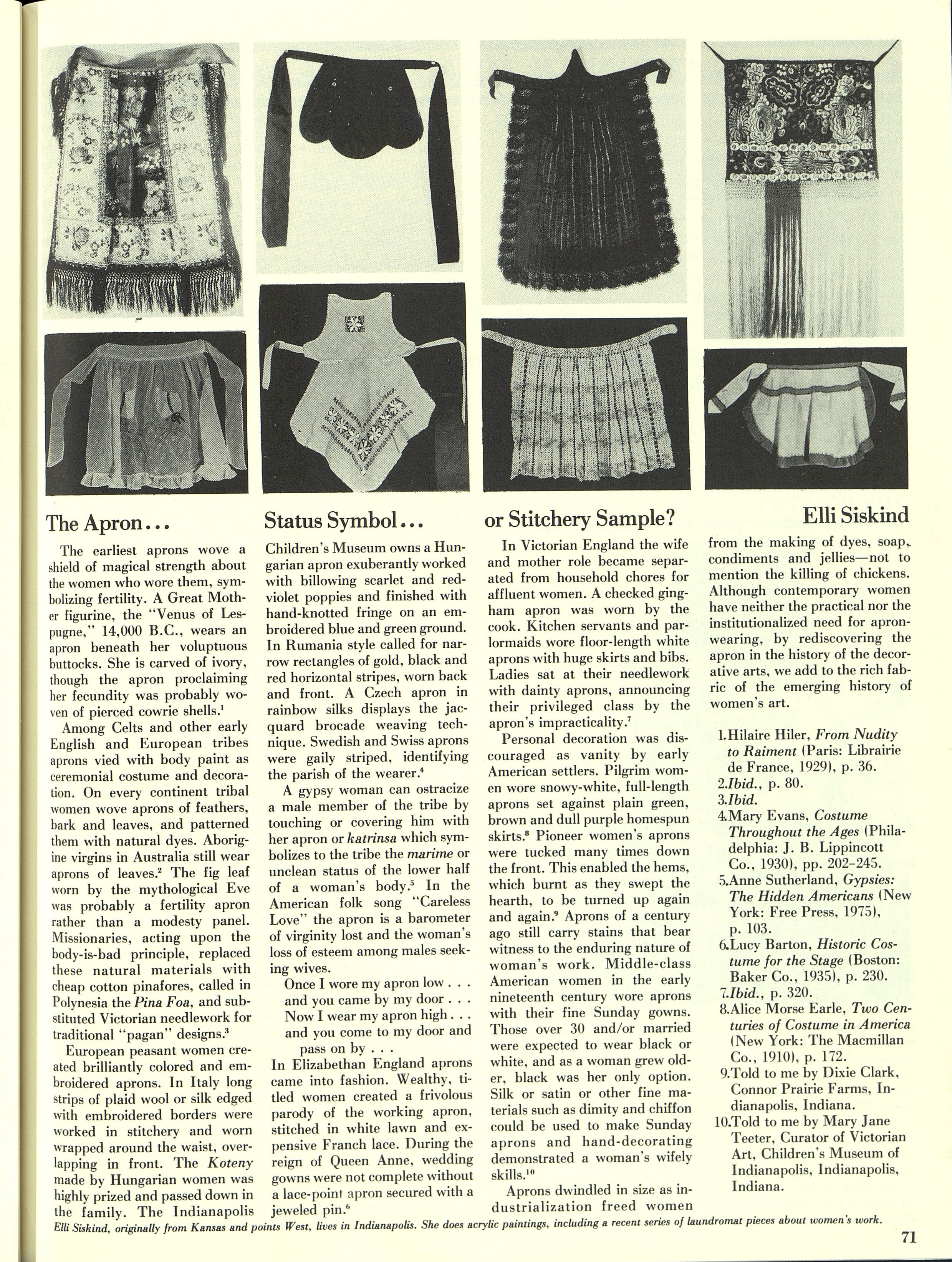

The earliest aprons wove a shield of magical strength about the women who wore them, symbolizing fertility. A Great Mother figurine, the "Venus of Lespugne," 14,000 B.C., wears an apron beneath her voluptuous buttocks. She is carved of ivory though the apron proclaiming her fecundity was probably woven of pierced cowrie shells.

Among Celts and other early English and European tribes aprons vied with body paint as ceremonial costume and decoration. On every continent tribal women wove aprons of feathers, bark and leaves, and patterned them with natural dyes. Aborigine virgins in Australia still wear aprons of leaves. The fig leaf worn by the mythological Eve was probably a fertility apron rather than a modesty panel. Missionaries, acting upon the body-is-bad principle, replaced these natural materials with cheap cotton pinafores, called in Polynesia the Pina Foa, and substituted Victorian needlework for traditional "pagan" designs.

European peasant women created brilliantly colored and embroidered aprons. In Italy long strips of plaid wool or silk edged with embroidered borders were worked in stitchery and worn wrapped around the waist, overlapping in front. The Koteny made by Hungarian women was highly prized and passed down in the family. The Indianapolis Children's Museum owns a Hungarian apron exuberantly worked with billowing scarlet and red violet poppies and finished with hand-knotted fringe on an embroidered blue and green ground. In Rumania style called for narrow rectangles of gold, black and red horizontal stripes, worn back and front. A Czech apron in rainbow silks displays the jacquard brocade weaving technique. Swedish and Swiss aprons were gaily striped, identifying the parish of the wearer.

A gypsy woman can ostracize a male member of the tribe by touching or covering him with her apron or katrinsa which symbolizes to the tribe the marime or unclean status of the lower half of a woman's body. In the American folk song "Careless Love" the apron is a barometer of virginity lost and the woman's loss of esteem among males seeking wives.

Once I wore my apron low...

and you came by my door...

Now I wear my apron high...

and you come to my door and

pass on by...

In Elizabethan England aprons came into fashion. Wealthy, titled women created a frivolous parody of the working apron, stitched in white lawn and expensive Franch lace. During the reign of Queen Anne, wedding gowns were not complete without a lace-point apron secured with a jeweled pin.

In Victorian England the wife and mother role became separated from household chores for affluent women. A checked gingham apron was worn by the cook. Kitchen servants and parlormaids wore floor-length white aprons with huge skirts and bibs. Ladies sat at their needlework with dainty aprons, announcing their privileged class by the apron's impracticality.

Personal decoration was discouraged as vanity by early American settlers. Pilgrim women wore snowy-white, full-length aprons set against plain green, brown and dull purple homespun skirts. Pioneer women's apron were tucked many times down the front. This enabled the hems, which burnt as they swept the hearth, to be turned up again and again. Aprons of a century ago still carry stains that bear witness to the enduring nature of woman's work. Middle-class American women in the early nineteenth century wore aprons with their fine Sunday gowns. Those over 30 and/or married were expected to wear black or white, and as a woman grew older, black was her only option. Silk or satin or other fine materials such as dimity and chiffon could be used to make Sunday aprons and hand-decorating demonstrated a woman's wifely skills.

Aprons dwindled in size as industrialization freed women from the making of dyes, soap, condiments and jellies—not to mention the killing of chickens. Although contemporary women have neither the practical nor the institutionalized need for apron-wearing, by rediscovering the apron in the history of the decorative arts, we add to the rich fabric of the emerging history of women's art.

Elli Siskind, originally from Kansas and points West, lives in Indianapolis. She does acrylic paintings, including a recent series of laundromat pieces about women's work.