Janet MacGaffey

The superb work done by some African potters has been neglected as an art form and, since pottery is fragile and hard to transport, few examples of their work appear in museums. Potters among the Kongo people of Western Zaire in Central Africa are women and, in the region in which I lived during the course of anthropological fieldwork, they make a matte black ware. Its production continues to flourish in the face of competition from factory-made products, although on a smaller scale than in the past, because the potters have adapted the form and function of their pots to changing social conditions.

One of these potters is Mayivangwa Thérèse. Watching her making a pot, one is struck by her absolute absorption and obvious satisfaction and enjoyment in perfecting its shape and decorating it. Sometimes she sings to herself as she smoothes a surface or incises a hatched band of decoration. Her meticulous care in achieving a perfectly shaped pot or delicately attached molded ornamentation is the mark of a perfectionist and her works are masterpieces of the potter's art.

To reach her village, Mbanza Manteke, I found a local truck carrying passengers and produce. The houses in Manteke are strung along the road and vary from cement block to adobe brick to wattle and daub. Arriving in the village on a hot afternoon I found Mayivangwa sitting on a mat behind her house making pots. She does not do this every day since potting is a part-time occupation that has to be fitted in with all the other things a Kongo woman does. Women produce and prepare all the food—sowing, cultivating and harvesting the crops—as well as fetching water and firewood, and caring for their homes and children. When potting, Mayivangwa works for most of the day, making a number of pots in each of several styles, drying and storing them until she has a number suitable for firing.

The village of Mbanza Manteke has a population of 582. It is the seat of local government for the district and has a school, dispensary and the offices of the mayor and police, but most of the villagers are subsistence farmers with little money. The village is isolated from town life with its stores and businesses, which is why Mayivangwa's pots are still in demand in the village despite the influx into Zaire of enamel ware, cheap crockery and aluminum pots and pans.

Traditionally pots were made for purely utilitarian purposes; their decoration and artistic merit varied according to the talent and creativity of the potter. Big conical vessels for cooking were set over an open fire on three hearthstones; small bowls were used for eating and drinking; small water carriers fit into a long, narrow, plaited palm-frond basket carried from the spring on a woman's head; large jars two feet high were kept in houses to store and cool water.

A Kongo woman has a budget separate from her husband's; once she has fed her family she can do what she wants with the surplus produce of her fields and keep the proceeds if she sells it. Likewise a potter keeps the money she earns from selling pots. Note: This aspect of the Kongo society ties into ideas of women's independence

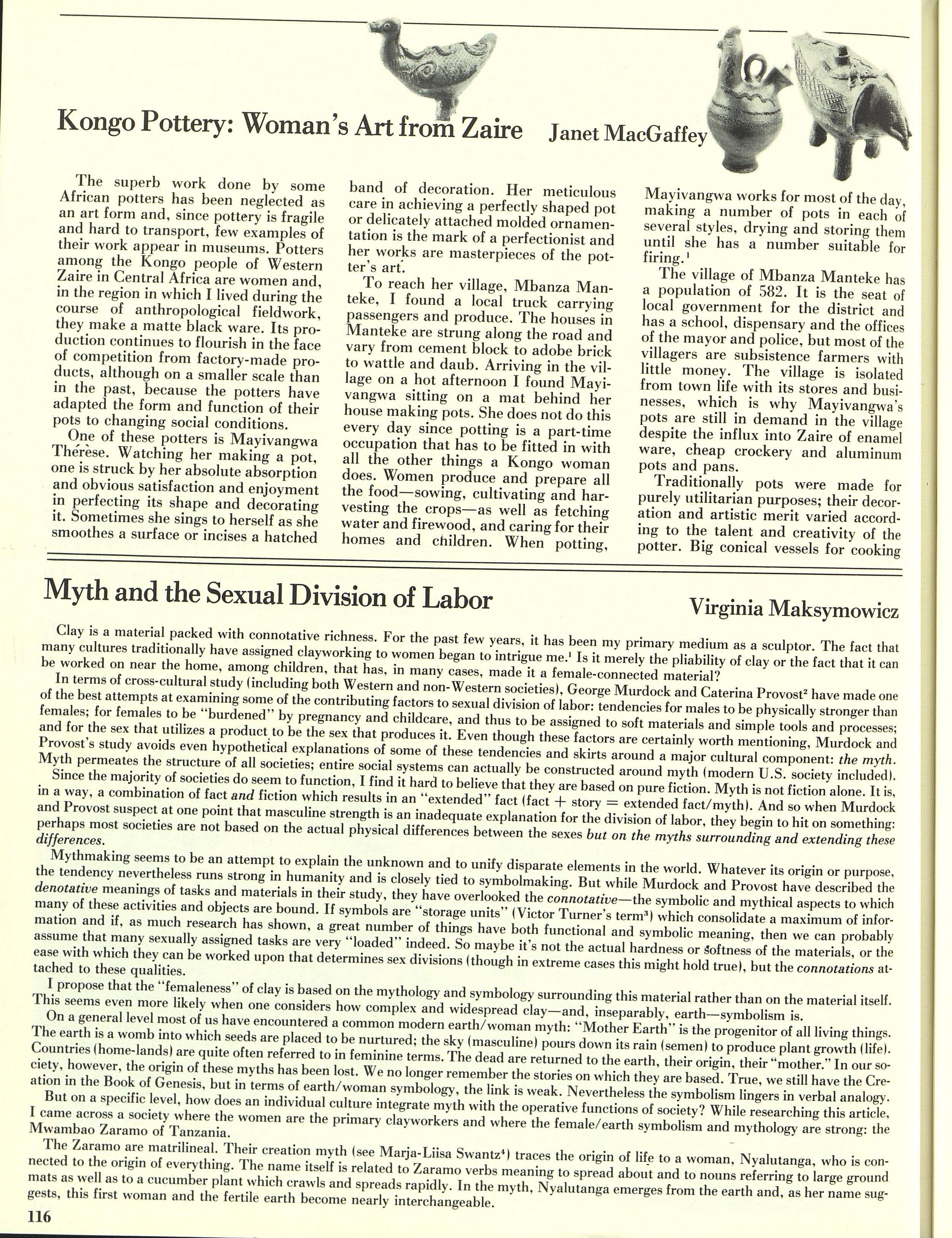

Mayivangwa sells her pots for a small sum in the village: in 1965 the price was about 25 cents. Sometimes she takes some to Kinshasa where they fetch about six dollars in the Ivor Market, a big market in the city center catering to tourists and the wealthy. The reason for the higher price in the city is a change in the function of these pots: from being considered purely utilitarian objects they are now in demand in the city as items of traditional art. For some time Mayivangwa has been making a number of purely ornamental pottery pieces, as well as the traditional utilitarian forms, to cater to this new art market. Some examples are shown here: two elephants, a water pot in the form of a chicken and a duck. They reflect the influence of European ornamental china animals that Mayivangwa has seen in stores or that have been brought home to the village by sailors, but she has created her own Africanized version, decorated with molded snakes and lizards. These creatures also appear on her water pots. Their significance is that they are considered by the Kongo to be mediators between this world and the other world of the dead: in Kongo cosmology water and amphibians are believed to mediate between the two worlds.

At the National Fair in Kinshasa in 1970 some of Mayivangwa's pitchers and ornamental pieces were exhibited. She had previously won prizes at similar events. Hers were the only pots from Lower Zaire in the exhibit; potters of her ability are rare in this area.

Generally potters pass on their skills to a relative. Mayivangwa is teaching her sister who lives in Kinshasa. These Kongo women are adapting to industrialization and urbanization by maintaining traditional forms appropriate to life today and responding creatively to changing needs.

1 For a detailed description of potmaking and pots see my article “Two Kongo Potters,” African Arts, Vol. IX, No. 1 (October, 1975).

Janet MacGaffey is an anthropologist and teacher. She lived in Zaire for two and a half years and has a special interest in African art and literature. She lives in Haverford, Pennsylvania.