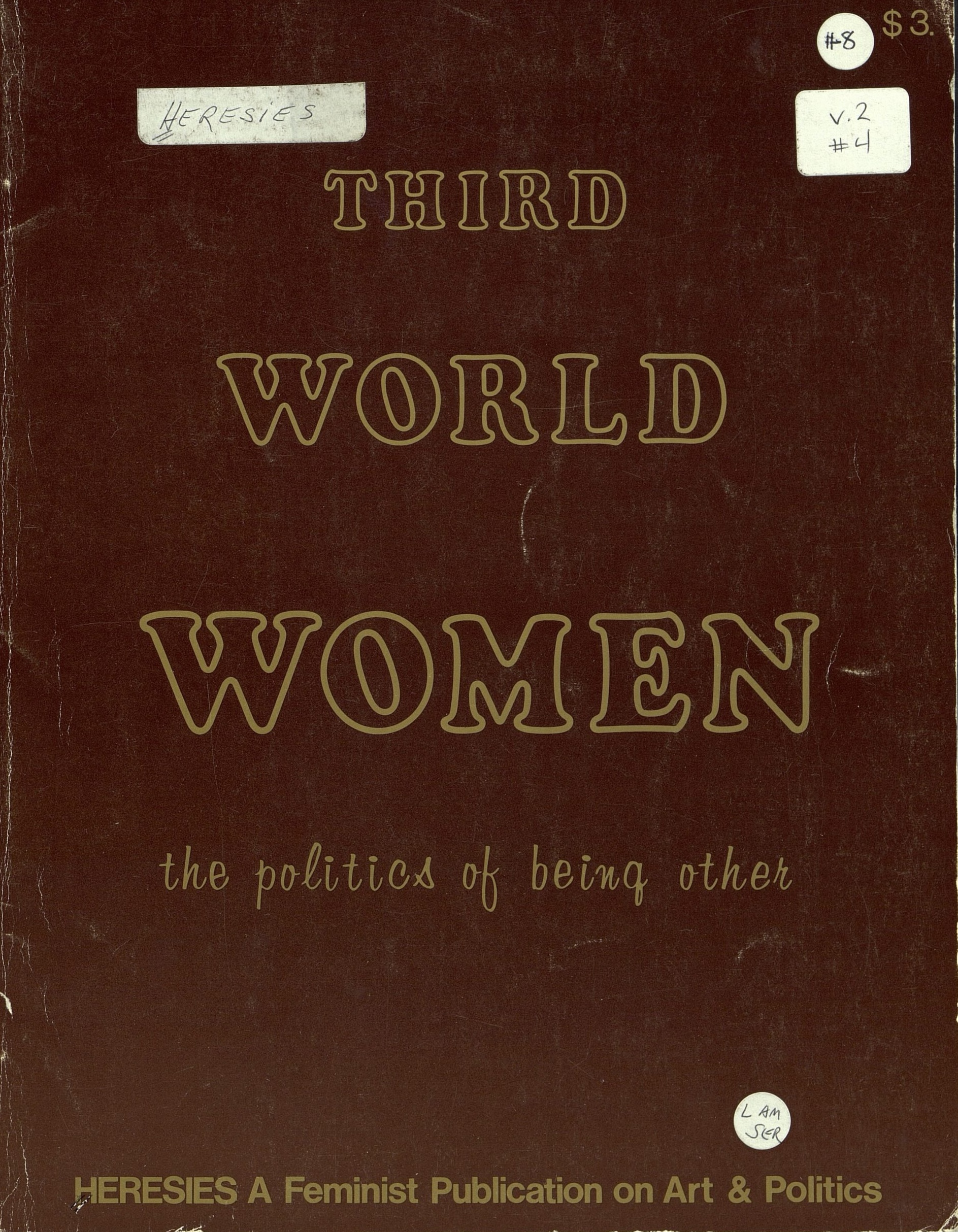

Third World Women: The Politics of Being Other

Heresies Vol, 2, No. 4, 1979

-

-

Issue 8 Collective

Editorial Collective: Lula Mae Blocton, Yvonne Flowers, Valerie Harris, Zarina Hashmi, Virginia Jaramillo, Dawn Russell, Naeemah Shabazz

Design Group: Lula Mae Blocton, Zarina Hashmi, Virginia Jaramillo

Staff: Sue Heinemann, Alesia Kunz, Sandy De Sando

Others who helped: Su Friedrich, Harmony Hammond, Lucy Lippard

From the Issue 8 Collective

Some of us came to this editorial collective wanting to work with other Third World women to break the isolation of racial/sexual tokenism experienced in college, on the job, in the women’s movement and in the “art world.” To exchange ideas. We realized our invisibility in the women’s, feminist and art communities. Some of us had questions about accomplishing the work of putting out this magazine, given the myths about us and our lack of experience in working together. Others did not question the work itself, given the energies and skills that we have used to survive. Some were leery and frightened of the interactions that might occur during the process; others were intrigued by these possibilities.

To describe who we are is exciting. We are painters, poets, educators, multi-media artists, students, shipbuilders, sculptors, playwrights, photographers, socialists, craftswomen, wives, mothers and lesbians. In the beginning we were Asian-American, Black, Jamaican, Ecuadorian, Indian (from New Delhi) and Chicana; foreign-born, first-generation, second-generation and here forever. We are all of these and this is extremely hard to define. The phrase Third World has its roots in the post-World War II economic policies of the United Nations, but today it is a euphemism. We use it knowing it implies people of color non-white and, most of all, “other. Third World women are other than the majority and the power-holding class, and we have concerns other than those of-white feminists, white artists and men.

Those of us on the collective spoke of being nonmarketable artists. We talked about how our creativity is drained off by menial labor in order to survive, and how, as Third World women artists, we are invisible in the white feminist art culture that operates on a buddy system like that of the white male culture at large.

It was frightening when we spoke of not always understanding each other, not trusting each other, and valuing different ideas and ways of being. With all the sameness of our double racial/ sexual oppression, our differences frequently did get in the way. We had a lot to learn about each other, our varying class identifications, cultural history, symbols and tones of our lifestyles, customs and prejudices. It was too much to learn even in almost two years of working together. We still do not always understand each other in terms of who our cultures, lifestyles and oppressions have made us be. But in working together we had to acknowledge the personal power inherent in who we are.

Our initial meetings were exploring, supportive, reaffirming—sometimes like group therapy. But this changed as we got deeper into the work. We established various kinds of working relationships around the tasks to be done, based on skills, interests, work schedules, proximity, etc. Sometimes becoming very close and remaining that way; other times the closeness fading as soon as the shared task was done.

Certain questions arose and were only partially answered. Is there a difference in the way feminism functions among Third World women and white women? Can working relationships be established and maintained between lesbian and heterosexual Third World women? Can Third World women afford to participate in volunteerism, since we have little, if any, financial security as it is? Can we as Third World women work collectively? Do we recognize that many of us actually practice feminist modes of being while rejecting them in theory?

There is one issue that was a surprise, but maybe we always knew about it. It is the intensity of our way of relating to each other. We trigger deep feelings and equally intense responses. We yell and shout and curse and laugh, get angry or protective or critical, caring or domineering, all on a grand scale. It can be frightening, and it probably was for most of us. Some realized that it was all right, while others couldn’t take it and left. There are probably very real and sound reasons for this to be the way we relate to each other. In the future, when we understand it, we will probably be able to change. But until then we should not let it stop us from working together. Too often in the past it probably has. We can and will move beyond this.

Another issue that plagued us throughout the year and a half was our relationship with the Heresies collective. It vacillated from our being vaguely aware of their presence while we were engrossed in our work, to reactions of anger and suspicion because of unclear or double messages that we felt were racist and paternalistic. Interestingly enough, we all recognized these incidents when they happened. Since there are no Third World women on the Heresies collective, our editorial group did not have a liaison who was knowledgeable or sensitive to Third World women’s issues. Communications were frequently awkward, confusing and presumptuous. Some writers, artists and activists would not submit their work, viewing the Heresies collective as racist and feeling the collective was using us, making no real efforts to correct the ongoing situation. When decisions were being made about our efforts and issues without any consultation with us, it was enraging and exploitative. We found ourselves without the resources, organizations, connections or the finances to do anything about it. Too often we had to come to a reassessment of why we were here in the first place.

What did we envision the end product to be? A reflection of all of us—those of us who stuck it out and those who couldn’t take it. Those women we understand in terms of their lives, their art and their politics, and those women who live their lives very differently from us, who express themselves differently through their choice of subject matter, media and style. Of course, we realized it was impossible to actually represent all the experiences and concerns of every Third World woman, but omissions on our part in no way deny the meaningfulness of their existence or art. We tried to put their work and ideas out there for others to see, for that was our primary reason for coming together. Isn’t that what the “politics of being other should be about? Let all our sisters come out of the shadows. We are alive and real and creating, too.