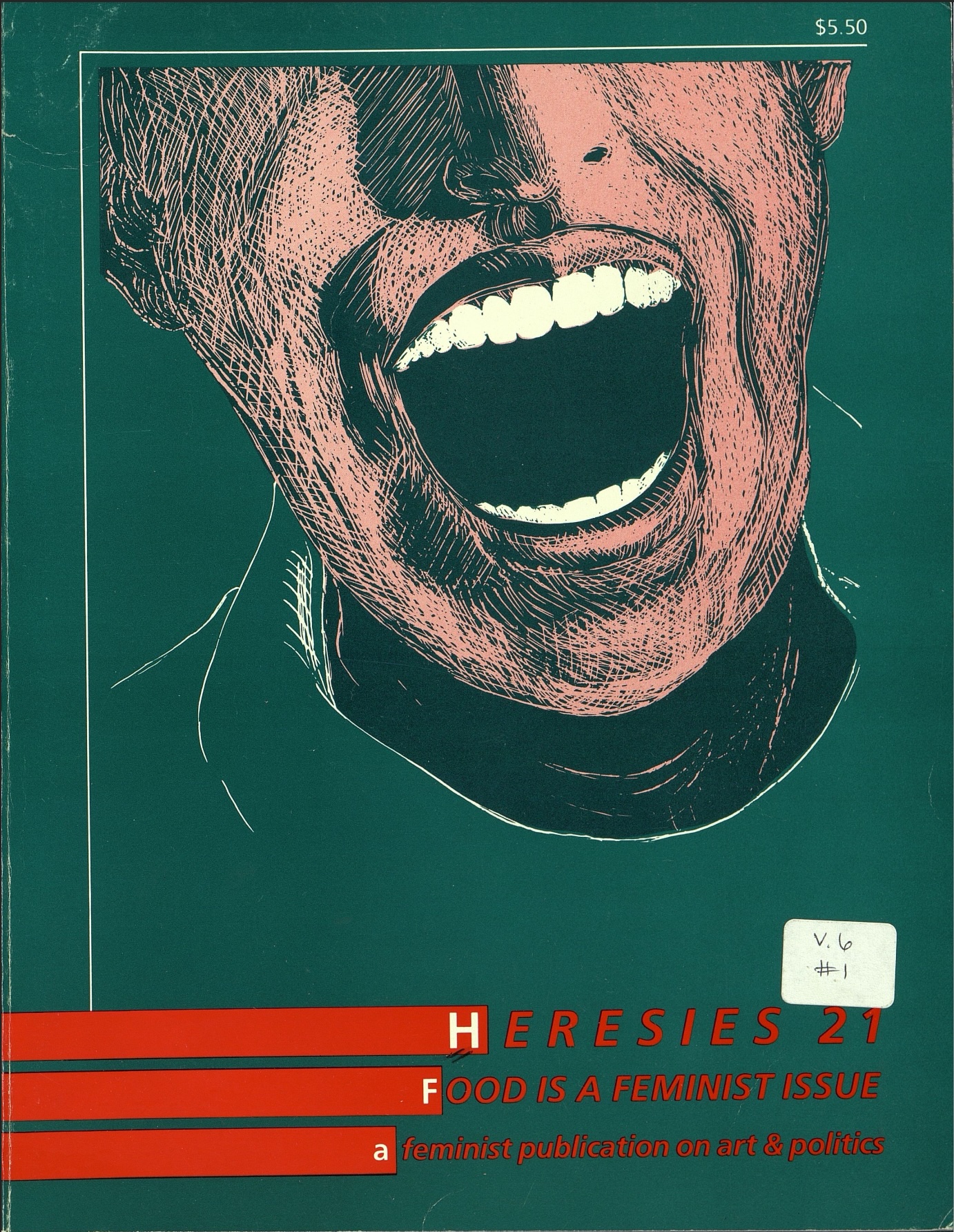

Food is a Feminist Issue

Vol. 6, No. 1, 1987

-

-

Read the Issue

Explore Issue #21 in PDF format with full-text search or as individual entity-tagged TEI documents (coming soon).

The Issue 21 Collective

Editorial Collective: Gail Bradley, Kathie Brown, Carrie Cooperider, C. Palmer Fuller, Pennelope Goodfriend, Kay Kenny, Bea Kreloff, Sondra Siegal

Editorial Help: Sue Heinemann, Elizabeth Hess, Avis Lang

Design: Kathie Brown, Carrie Cooperider, Kay Kenny, Bea Kreloff, Robin Michals

Typesetting: Kathie Brown, Morgan Gwenwald

Production: Bendel Hydes, Gail Bradney, C.C. Kinsman, Robin Michals

From the Issue 21 Collective

Food for Thought

Food is necessary for human survival. But it’s much more than that, for food is a primary pleasure. Social bonding and celebration take place around food. For women, in particular, our relationship to food is a very personal one. At the most fundamental level, human life depends on a woman for its very being. A woman’s body feeds the unborn child. Her breast milk provides the infant’s first food outside of the womb and contains antibodies, the child’s first medicine. An infant’s primary instinct is to survive; its first wail a callinq out for food. Food, then, is at the heart of lanquage and the first medium of exchange a child discovers.

As the original providers of food, women are sustainers of life and continue that role as cooks, smart shoppers, waitresses, health care professionals, social workers, market sellers, and small farmers. But since a woman’s individual power—the power to control her own conditions and the conditions of her children—has been taken out of her hands, issues related to feeding and nurturing have moved out of the personal, and into the political realm.

In the beginning, they say, Eve ate that tempting apple. And where did it get her? Eve gained knowledge, yes, but she would now have to suffer pain in childbirth. Her hunger caused humans to become mortal and ashamed, so the story goes. But the most important consequence of her ravenous appetite is that Eve lost her autonomy —man would rule over woman, and her desires would now be subject to her husband’s.

The Adam and Eve story symbolizes what has happened to women on a larger scale. Meeting women’s needs is now contingent on the will of patriarchal religious and economic powers; these powers have stepped into the role of husband to make decisions affecting our own, and our children’s, well-being. The loss of women's independence has had far-reaching effects.

Women are stillexpected to provide and/or prepare the family’s food even though we’re not given the resources and power to do so on our own. And industrialists and advertisers prey on women by offering us food that is more visually appealing, but less nutritious, giving us a false sense that we have options. The many foods available on the market divert women’s attention away from how very little real, significant choice we have about our lives, about our world.

A woman’s body and her relationship to food is a paradigm for the use and control of food in the world. Just as food, a powerful tool, is used as punishment or reward within families (eat your spinach or you won’t get dessert), on a larger scale, food policies are used as potent political weapons between and within nations. In the third world, women do more than consume food; they also produce the majority of the food in those countries. Yet these women have little control over its distribution and are thus impoverished as a direct result of their lack of power. Traditionally the last to eat, third world women get the least food, or are prohibited through food taboos from eating some of the most desirable (and nutritious) foods.

Those with less power come to be viewed as somehow less than human The predominant male attitude toward women is that we are objects, just like other products. In the not-too-distant past, women were seen as something to be devoured, which is apparent in male cannibalistic lanquage —the analogous use of such words as tomato, peach and cupcake to describe women and the met aphorical meanings behind such traditions as a woman popping out of a cake at a stag party. Being viewed as succulent, juicy and luscious has affected how we see ourselves. In the last two decades or so, our packaging has changed somewhat, but women are still seen as commodities. Now, especially in affluent cultures, to be thin (read "ideal") is to be desirable. Hence, many of us are obsessed with our body size. Through our refusal or over consumption of food, women get caught in cycles of meeting or defying societal standards. Anorexia, bulimia, and overeating are reactions to political situations that have become trivialized as personal ones. Our striving to conform to the ideal body size diverts women’s attention, energy, and thinking away from considering social and political action.

Central to each of these issues is how food and feeding are manipulated by others and how women’s power to nurture has been taken out of our hands. These are personal and political concerns. For women, issues relating to food can and must fuel feminist sensibilities. -GB for the Heresies 21 collective