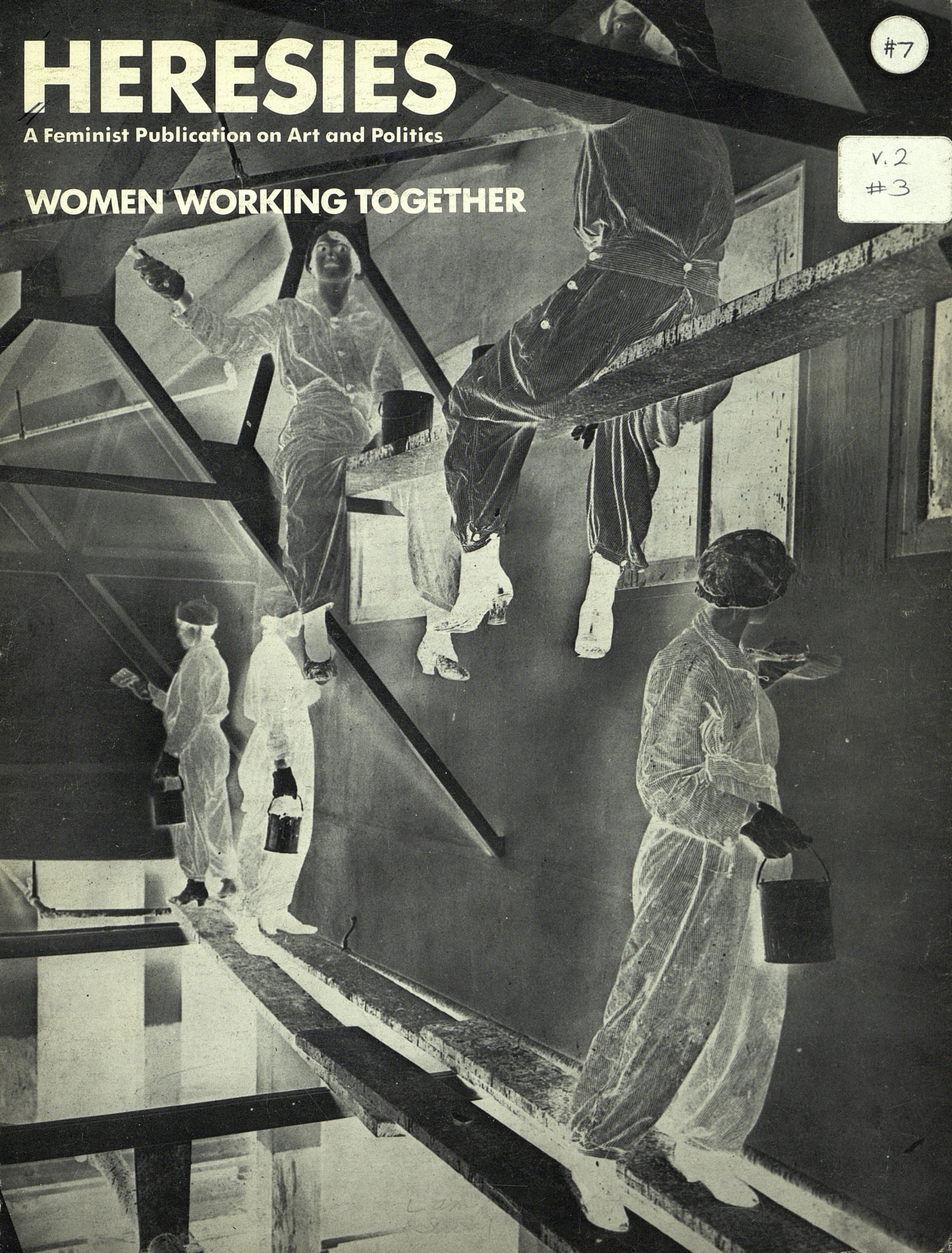

Women Working Together

Heresies Vol. 2, No. 3, Spring 1979

-

-

The Issue 7 Collective

Heresies collective: Ida Applebroog, Patsy Beckert, Joan Braderman, Su Friedrich, Janet Froelich, Harmony Hammond, Sue Heinemann, Elizabeth Hess, Arlene Ladden, Gail Lineback, Lucy Lippard, Melissa Meyer, Marty Pottenger, Carrie Rickey, Elizabeth Sacre, Miriam Schapiro, Amy Sillman, Elke Solomon, Pat Steir, May Stevens, Elizabeth Weatherford, Sally Webster

Associate members: Mary Beth Edelson, Joyce Kozloff, Joan Snyder, Michelle Stuart, Susana Torre, Nina Yankowitz

Staff: Birgit Flos, Sue Heinemann, Gail Lineback

From the Issue 7 Collective

EDITORIAL

The Heresies #7 Editorial Collective.

We haven’t yet learned to analyze 'women working together.' When a group is working well,

we assume nothing is worth analyzing. When problems get hairy, we’re so bummed out that we grab

the handiest explanation (’If only she’d stop doing

that, everything would be okay’; Nobody is committed

enough’ ). Women need to develop ways of thinking,

looking, talking about our processes. That it is frequently painful to work together cannot be permitted

to excuse us from examining what is going on. In the

women’s movement, we finally started sharing bedroom secrets. It’s about time we talk as frankly about

the internal cleanliness and dirt in our collectives.

Eventually, the sacred moral tones can be replaced by

practical discussions that could also provoke exciting

analysis.

We have been working together

for about a year. We share a sense

of confusion, disappointment and

frustration as we look back. For a

while, the causes of our malaise

were obscure to us. Although we

had our share of angry exchanges,

we did not suffer from evident political division or serious, chronic, per-

sonal antagonism.

I have really enjoyed the people

working on the issue. Getting to

know the women has been important

to me.

In general, the women in our group

are clear about themselves and their

lives and have shown themselves to

be pretty open and direct in dealing

with each other.

We established a “friendly-but-

impersonal collegial atmosphere’

which we would only later call a

conspiracy of niceness. Months

later, we remain friendly, more often

than not “cheerful and polite with

“comfortable in our

each other,

work.

Yet something went wrong.

It was far more boring than it was

stimulating.

The decision-making processes have

been tedious and verbose.

It seemed that we so often looked for

the weak points in the articles we received (or in the back issues of Heresies) that I began to lose confidence

and interest.

Our “conspiracy of niceness” took

its toll. Although we might have been

“appalled that one or two people

could, at times, so effectively control

the time, energy and direction of the

group,” we were usually “too polite’

to name—let alone to deal with—the

problem. A kind of disaffection set

in; as a result, “we did not allow

ourselves to respect our mutual decisions. And, it seemed:

We know very little about one another’s lives.

We don’t respect each others’ feelings about writing solicited or submitted.

Everyone in the collective seemed to

connect through a web of mutual

acquaintances with other members

of the collective or people outside—

whom I never knew or had heard of.

I ended up feeling insignificant.

While we made some alliances

based on past friendships and current social, sexual and political allegiances, they were neither fierce nor

exclusive. Yet most of us felt locked

out, by and large, from what seemed

to be a cohesive group for the others.

Not surprisingly, in such an atmosphere,

We never became a work group, only the seeds of one. We did not agree

on our goals or the means we would

and wouldn’t use to meet them. Since

we did not commit ourselves to anything, we have not been able to demand much from each other nor has

the main Heresies Collective been

able to demand much from our group.

A certain cynical pragmatism became the dominant element of our

working together.

We talked, argued a bit, but never

became passionate. We became very

pragmatic decision-makers, reluctant workers, bare friends.

It is not a work environment I would

choose if there were other possibilities.

Now, toward the end of the time

we’ve worked together, we have

identified at least three of the causes

of our situation: our subject, our relation to the main collective, and our

prior self-identification as artists or

writers. From the outset, we found it

difficult to focus our issue’s topic.

We agreed that we were interested

in the experiences women had had

and the methods that had been developed in working together, in

either alternative or traditional

work structures. We did not want

sentimentality or idealization, but

“true confessions” of conflicts,

doubts and ambitions. Some of us

were primarily interested in traditional structures and ways of changing them. Others dwelt on general

questions about the meaning of work

or on conflicts between professionalism and feminism. Occasionally, it

seemed we wanted to include almost

anything women might do together

as part of our interest. These differences in emphasis caused some

misunderstanding and difficulty

within our group as we evaluated

the material we received or discussed solicitations.

Much more serious were the problems with our topic as we mutually

understood it. We—women in general—scarcely have a vocabulary

for talking about women working together. We hardly know the outline

of the subject, much less how to define solutions to its problems. There

are serious obstacles to “truth-

telling” among women, of which we

are only now aware. It often means

identifying specific people, which

threatens relationships and projects;

it requires self-exposure and makes

us feel vulnerable. For weeks, our

group could not understand why it

was so difficult to get material which

addressed our questions in an interesting, intelligent way. Now we

know that we are all inexperienced

in dealing with our subject, emotionally and conceptually.

In retrospect, we realize that

there was a vacuum —a lack of focus around which we could define

political and intellectual issues. Because we weren’t clear about our

topic, it was easy to make our goal

merely to get out the magazine. We

complained that we weren’t talking

enough, that there was too much

business, too little camaraderie,

politics or debate. We momentarily

would become “passionate” about

procedural matters or a particular

article. But this was no substitute for

political passion about substantive issues—hard to achieve about a topic which is both new and disturbing.

Because of the lack of passion and

goals, we were not sufficiently motivated to explore and modify the

personal relationships we felt were

increasingly unsatisfying.

These problems were compounded

by the particular history of our issue.

This issue originally was intended

as a project of the main Heresies Collective. It was to be a statement about

and examination of their process

and history, along with “true confessions” from other women’s groups

and collectives. When Heresies

realized they could not follow

through with their project, they

opened up the issue to the feminist

community. Coming to this decision

took time and meant, paradoxically,

that the issue was “late” before our

editorial group had ever met. We

were confronted with a practical

task: to put out an issue quickly, according to the schedule demands

and topic definition of the Heresies

Collective.

At first we were a shifting group

of women who appeared to be under

the direction of whichever member(s) of the main collective hap-

pened to be at that night’s meeting.

It was their task to clarify the project and to communicate a sense of

urgency about Heresies’ schedules.

Throughout the production of this issue, we have worked with a series of

unrealistic and unnerving deadlines

which blighted our spirits, inhibited

our thinking and bred numerous

resentments. By the time we might

have calmly and productively talked

of ways of finishing our project, we

no longer trusted ourselves or Heresies to be honest about any deadline,

and many of us could no longer care.

The three members of Heresies

who were part of our group were

torn between our editorial interests

and those of Heresies. The rest of us

came with varying degrees of commitment to, and familiarity with, the

magazine. But whatever our initial

allegiances, most of us occasionally

felt harassed and misunderstood by

a collective whose operations were

confusing, even unintelligible to us.

It was easy to feel antagonistic

toward the very group for whom we

were working and who made our existence possible. We had conflicts

with the larger collective over the

size of the issue, its budget, and our

time schedule. These problems became more explicit as our project

wore on. We sometimes felt that the

final control over “our” magazine

lay in “their” hands. This tended to

reinforce the sense of an adversarial

relation.

In our final months we have developed still another division—a strongly marked version of the split between writers and artists, which we

tend to justify as a split between

editorial and design. This division

has compounded the disconnectedness of the group.

The schism between the artists and

writers is very apparent. There is a

politic in it that hasn’t been dis

cussed. I am appalled to think that

discussion could be considered bullshit and that visuals could be seen

as merely decorative.

We decided collectively about the

value of written material. We were

shown visuals, but we didn’t discuss

them much and certainly didn’t vote

on them collectively. I couldn’t find

words to ask about the politics or

meaning of the visuals. I feel cut off

from a large part of the magazine.

My level of ambivalence about the

content of the issue is enormous. l’m

primarily concerned about design

and visuals.

I care more for the look and feel of

the publication, now, than for the

editorial work. I want to design a

beautiful magazine with the few of

us who care about design. I hope

that the editorial material will carry

its own weight, but I seem to have

separated myself from that.

At times it has seemed as if we

have two subcollectives with occasional cross-overs. Some of us didn’t

see each other for weeks.

All this is disheartening. But we

have stayed on. There are still ten of

us actively putting out the magazine.

We came together recently to reflect

upon our individual and collective

experiences. Now, at last, we are

engaging in the kind of nonjudgmental self-criticism necessary to group

projects. We have worked hard,

laughed a lot, and are feeling better

about our experience.

Although we are not happy with

the way we’ve worked together, we

do like what we have produced. We

see this issue as a groundbreaking

one. We are presenting material

which, as a whole, may allow all of

us to begin to see what “women

working together” looks like. Women

have many options: more and more

women are exploring them and feeling good about the results. It is good

to work together, but it isn’t easy.

We must learn to make compromises

and relinquish control, at the same

time maintaining political passion

and assuming our responsibilities.

We hope that this issue adds to the

body of information and usable wisdom that women can draw upon, not

just for inspiration but for practical

help in analyzing and solving our

difficulties.