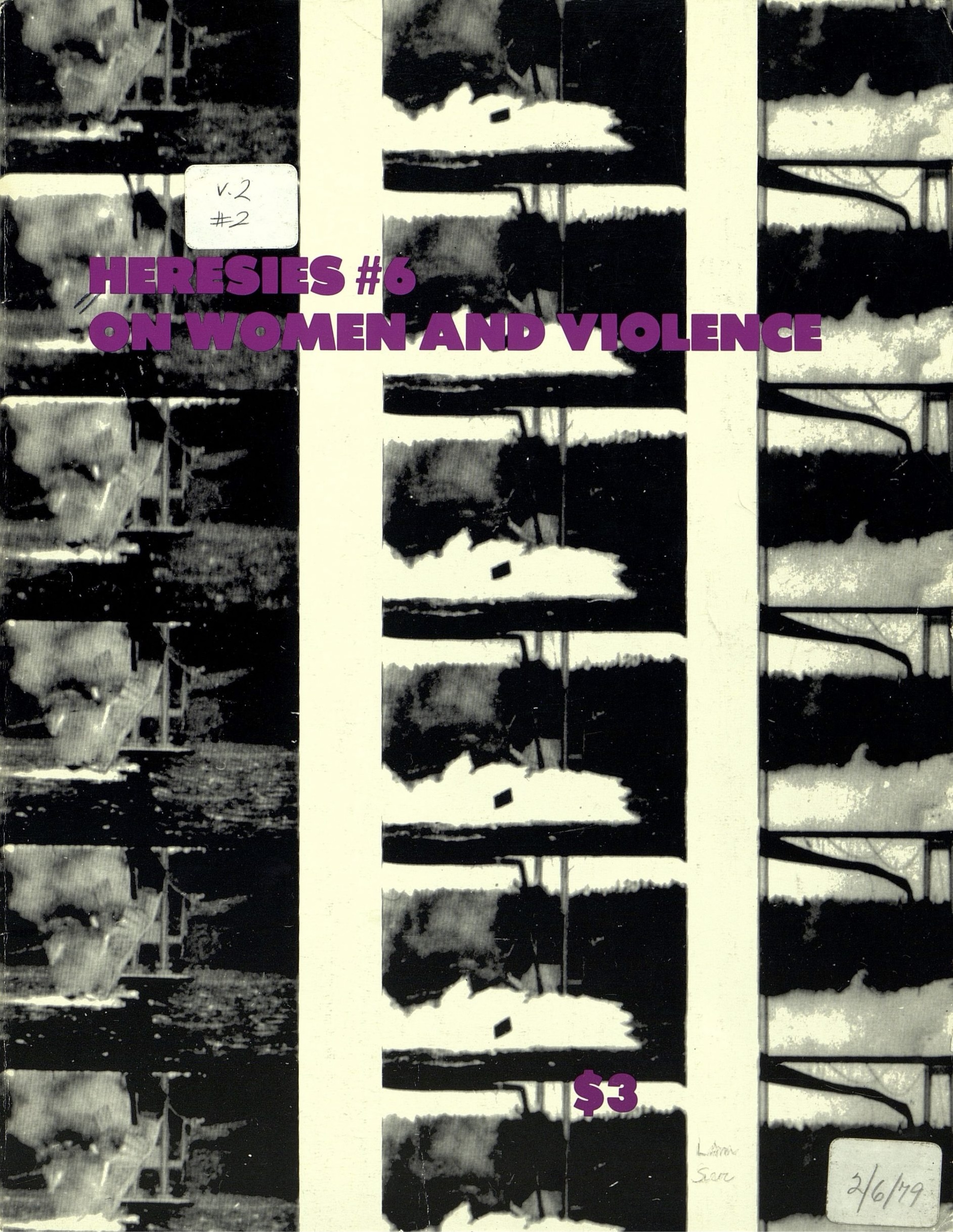

On Women and Violence

Heresies Vol. 2, No. 2, Summer 1978

-

-

From the Issue 6 Collective

We came together almost a year ago to examine violence. We operated as a

study group, a work group and a support group. Our individual reasons for

joining together to work on this issue included years of involvement in workplace organizing, work with tortured political prisoners in Chile, work with

battered women in New York City, three years’ work as a whore; to substantiate a psycho-sexual curiosity in violence; being molested and beaten by a

father, being raised by working-class communist parents, being lesbian, being

Indian in a White supremacist society. And all of us shared a commitment, as

women, to the radical restructuring of this society.

Readings and discussions about our individual experiences have helped us

clarify the inextricable connection between power, control and privilege: that

violence, in its broadest sense, is essential in maintaining any unequal relation¬

ship. We were forced to abandon linear notions about the causes, functions and

manifestations of violence and to replace them with an understanding that was

both multidimensional and itself a process.

In one-to-one relations, most of us at times have felt in control, powerful:

mothers over children, whores over tricks, females withholding something a

male wants. In a larger sense, however, this power is relative. If the laws, jobs,

money, and values that affect our lives are determined by men with power, then

the personal power we experience as mother, whore or girlfriend is never outside of this context.

Actual power can be elusive, not something you can hold in your hand. Power does not have a life of its own, but is established over and over again through

interaction. The power of some individuals, whether a caseworker, a husband

or a boss, and some institutions over others is culturally sanctioned and

enforced.

We recognize that violence is woven throughout the fabric of all social structures and that this violence is experienced differently according to cultural,

racial, sexual, class, ethnic, age and national identity. Those of us who are poor

in a classist society, Third World in a racist society, female in a sexist society,

homosexual in a heterosexist society know daily the violence directed at us because of who we are and the importance of uniting along these lines. But to

examine class and not race, class and race but not sex, or sex and nothing else,

perpetuates our isolation and undercuts the clarity of our analysis and the

strength of our united action.

Women have always fought back. We have fought for survival, for change

and for revolution. Recognizing and examining our identity as a gender class

enables us to challenge one of the most deep-rooted and long-lasting instances

of domination: that of men over women

Feminism takes as a central assumption that women as women are everywhere oppressed. The nature of this oppression may be modified by the partic-

ular male-dominated social system that a woman is part of, but as variable as

male domination may be, the central feature of the relations between the sexes

is differential access to societal resources and expropriation of one group’s

labor power by another group. So not only are women oppressed by social

custom and laws that deny them economic self-sufficiency, political visibility

and social status vis-à-vis men, but the labor power of all women (including

productive and reproductive) is ultimately under the control of men.

We have been working toward an issue that is more than a documentation of

the violence endured by women throughout herstory or a simple collection of

individual solutions. We have been working toward an issue that will stimulate

debate and contribute to the momentum of women effecting radical change.

Within the intersection of gender, violence and power exists one of the keys to

understanding oppression and resistance.

—The 6th Issue Collective