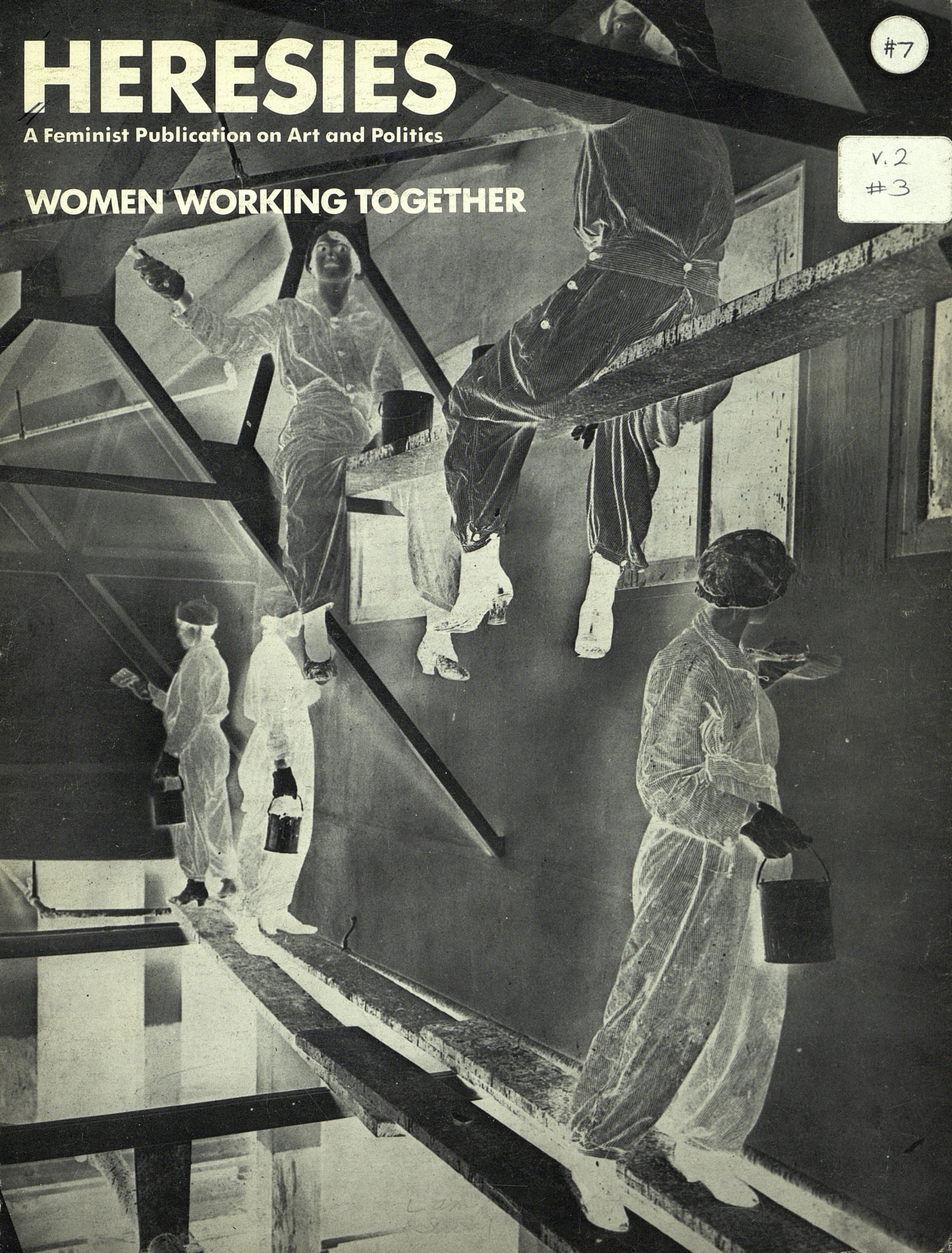

Women Working Together

Heresies Vol. 2, No. 3, Spring 1979

-

-

Read the Issue

Explore Issue #7 in PDF format with full-text search or as individual entity-tagged TEI documents (coming soon).

The Issue 7 Collective

Heresies collective: Ida Applebroog, Patsy Beckert, Joan Braderman, Su Friedrich, Janet Froelich, Harmony Hammond, Sue Heinemann, Elizabeth Hess, Arlene Ladden, Gail Lineback, Lucy Lippard, Melissa Meyer, Marty Pottenger, Carrie Rickey, Elizabeth Sacre, Miriam Schapiro, Amy Sillman, Elke Solomon, Pat Steir, May Stevens, Elizabeth Weatherford, Sally Webster

Associate members: Mary Beth Edelson, Joyce Kozloff, Joan Snyder, Michelle Stuart, Susana Torre, Nina Yankowitz

Staff: Birgit Flos, Sue Heinemann, Gail Lineback

From the Issue 7 Collective

EDITORIAL

The Heresies #7 Editorial Collective.

"We haven’t yet learned to analyze 'women working together.' When a group is working well, we assume nothing is worth analyzing. When problems get hairy, we’re so bummed out that we grab the handiest explanation (’If only she’d stop doing that, everything would be okay’; Nobody is committed enough’ ). Women need to develop ways of thinking, looking, talking about our processes. That it is frequently painful to work together cannot be permitted to excuse us from examining what is going on. In the women’s movement, we finally started sharing bedroom secrets. It’s about time we talk as frankly about the internal cleanliness and dirt in our collectives. Eventually, the sacred moral tones can be replaced by practical discussions that could also provoke exciting analysis.

We have been working together for about a year. We share a sense of confusion, disappointment and frustration as we look back. For a while, the causes of our malaise were obscure to us. Although we had our share of angry exchanges, we did not suffer from evident political division or serious, chronic, personal antagonism.

I have really enjoyed the people working on the issue. Getting to know the women has been important to me.

In general, the women in our group are clear about themselves and their lives and have shown themselves to be pretty open and direct in dealing

with each other.

We established a “friendly-but-impersonal collegial atmosphere’ which we would only later call a conspiracy of niceness. Months later, we remain friendly, more often than not “cheerful and polite with each other," “comfortable in our work."

Yet something went wrong.

It was far more boring than it was stimulating.

The decision-making processes have been tedious and verbose.

It seemed that we so often looked for the weak points in the articles we received (or in the back issues of Heresies) that I began to lose confidence and interest.

Our “conspiracy of niceness” took its toll. Although we might have been “appalled that one or two people could, at times, so effectively control the time, energy and direction of the group,” we were usually “too polite" to name—let alone to deal with—the problem. A kind of disaffection set in; as a result, “we did not allow ourselves to respect our mutual decisions. And, it seemed:

We know very little about one another’s lives.

We don’t respect each others’ feelings about writing solicited or submitted.

Everyone in the collective seemed to connect through a web of mutual acquaintances with other members of the collective or people outside—whom I never knew or had heard of. I ended up feeling insignificant.

While we made some alliances based on past friendships and current social, sexual and political allegiances, they were neither fierce nor exclusive. Yet most of us felt locked out, by and large, from what seemed to be a cohesive group for the others.

Not surprisingly, in such an atmosphere.

We never became a work group, only the seeds of one. We did not agree on our goals or the means we would and wouldn’t use to meet them. Since we did not commit ourselves to anything, we have not been able to demand much from each other nor has the main Heresies Collective been able to demand much from our group.

A certain cynical pragmatism became the dominant element of our working together.

We talked, argued a bit, but never became passionate. We became very pragmatic decision-makers, reluctant workers, bare friends.

It is not a work environment I would choose if there were other possibilities.

Now, toward the end of the time we’ve worked together, we have identified at least three of the causes of our situation: our subject, our relation to the main collective, and our prior self-identification as artists or writers. From the outset, we found it difficult to focus our issue’s topic. We agreed that we were interested in the experiences women had had and the methods that had been developed in working together, in either alternative or traditional work structures. We did not want sentimentality or idealization, but “true confessions” of conflicts, doubts and ambitions. Some of us were primarily interested in traditional structures and ways of changing them. Others dwelt on general questions about the meaning of work or on conflicts between professionalism and feminism. Occasionally, it seemed we wanted to include almost anything women might do together as part of our interest. These differences in emphasis caused some misunderstanding and difficulty within our group as we evaluated the material we received or discussed solicitations.

Much more serious were the problems with our topic as we mutually understood it. We—women in general—scarcely have a vocabulary for talking about women working together. We hardly know the outline of the subject, much less how to define solutions to its problems. There are serious obstacles to “truth-telling” among women, of which we are only now aware. It often means identifying specific people, which threatens relationships and projects; it requires self-exposure and makes us feel vulnerable. For weeks, our group could not understand why it was so difficult to get material which addressed our questions in an interesting, intelligent way. Now we know that we are all inexperienced in dealing with our subject, emotionally and conceptually.

In retrospect, we realize that there was a vacuum —a lack of focus around which we could define political and intellectual issues. Because we weren’t clear about our topic, it was easy to make our goal merely to get out the magazine. We complained that we weren’t talking enough, that there was too much business, too little camaraderie, politics or debate. We momentarily would become “passionate” about procedural matters or a particular article. But this was no substitute for political passion about substantive issues—hard to achieve about a topic which is both new and disturbing. Because of the lack of passion and goals, we were not sufficiently motivated to explore and modify the personal relationships we felt were increasingly unsatisfying.

These problems were compounded by the particular history of our issue. This issue originally was intended as a project of the main Heresies Collective. It was to be a statement about and examination of their process and history, along with “true confessions” from other women’s groups and collectives. When Heresies realized they could not follow through with their project, they opened up the issue to the feminist community. Coming to this decision took time and meant, paradoxically, that the issue was “late” before our editorial group had ever met. We were confronted with a practical task: to put out an issue quickly, according to the schedule demands and topic definition of the Heresies Collective.

At first we were a shifting group of women who appeared to be under the direction of whichever member(s) of the main collective happened to be at that night’s meeting. It was their task to clarify the project and to communicate a sense of urgency about Heresies’ schedules. Throughout the production of this issue, we have worked with a series of unrealistic and unnerving deadlines which blighted our spirits, inhibited our thinking and bred numerous resentments. By the time we might have calmly and productively talked of ways of finishing our project, we no longer trusted ourselves or Heresies to be honest about any deadline, and many of us could no longer care.

The three members of Heresies who were part of our group were torn between our editorial interests and those of Heresies. The rest of us came with varying degrees of commitment to, and familiarity with, the magazine. But whatever our initial allegiances, most of us occasionally felt harassed and misunderstood by a collective whose operations were confusing, even unintelligible to us. It was easy to feel antagonistic toward the very group for whom we were working and who made our existence possible. We had conflicts with the larger collective over the size of the issue, its budget, and our time schedule. These problems became more explicit as our project wore on. We sometimes felt that the final control over “our” magazine lay in “their” hands. This tended to reinforce the sense of an adversarial relation.

In our final months we have developed still another division—a strongly marked version of the split between writers and artists, which we tend to justify as a split between editorial and design. This division has compounded the disconnectedness of the group.

The schism between the artists and writers is very apparent. There is a politic in it that hasn’t been discussed. I am appalled to think that discussion could be considered bullshit and that visuals could be seen as merely decorative.

We decided collectively about the value of written material. We were shown visuals, but we didn’t discuss them much and certainly didn’t vote on them collectively. I couldn’t find words to ask about the politics or meaning of the visuals. I feel cut off from a large part of the magazine.

My level of ambivalence about the content of the issue is enormous. l’m primarily concerned about design and visuals.

I care more for the look and feel of the publication, now, than for the editorial work. I want to design a beautiful magazine with the few of us who care about design. I hope that the editorial material will carry its own weight, but I seem to have separated myself from that.

At times it has seemed as if we have two subcollectives with occasional cross-overs. Some of us didn’t see each other for weeks.

All this is disheartening. But we have stayed on. There are still ten of us actively putting out the magazine. We came together recently to reflect upon our individual and collective experiences. Now, at last, we are engaging in the kind of nonjudgmental self-criticism necessary to group projects. We have worked hard, laughed a lot, and are feeling better about our experience.

Although we are not happy with the way we’ve worked together, we do like what we have produced. We see this issue as a groundbreaking one. We are presenting material which, as a whole, may allow all of us to begin to see what “women working together” looks like. Women have many options: more and more women are exploring them and feeling good about the results. It is good to work together, but it isn’t easy.

We must learn to make compromises and relinquish control, at the same time maintaining political passion and assuming our responsibilities.

We hope that this issue adds to the body of information and usable wisdom that women can draw upon, not just for inspiration but for practical help in analyzing and solving our difficulties.